Seeing the forest

The latest research buzz: drones

Perched awkwardly in a stand of shrubby manzanita on a cool December day, Jon Detka swiveled a 20-foot swimming pool sweep in the air, a Bluetooth-equipped GoPro camera strapped to its tip. Steadying the long pole over the coastal brush, the UC Santa Cruz Ph.D. student in environmental studies snapped overhead photos of the woody plant he studies to measure the effects of the ongoing drought at UCSC’s Ford Ord Natural Reserve.

While waving his pool sweep over the brush, Detka also tried to avoid the chaparral’s dense, sharp, pointy branches, the poison oak, and the questing arms of Lyme disease–carrying ticks. Then, in the middle of these tricky maneuvers, Detka spied a group of interesting folks who had “come out to scout the Reserve for a drone camp event.” Seeing their drones nimbly buzzing about and hovering, the thought flitted into his mind: “Maybe I don’t have to walk through all this.”

Up and coming

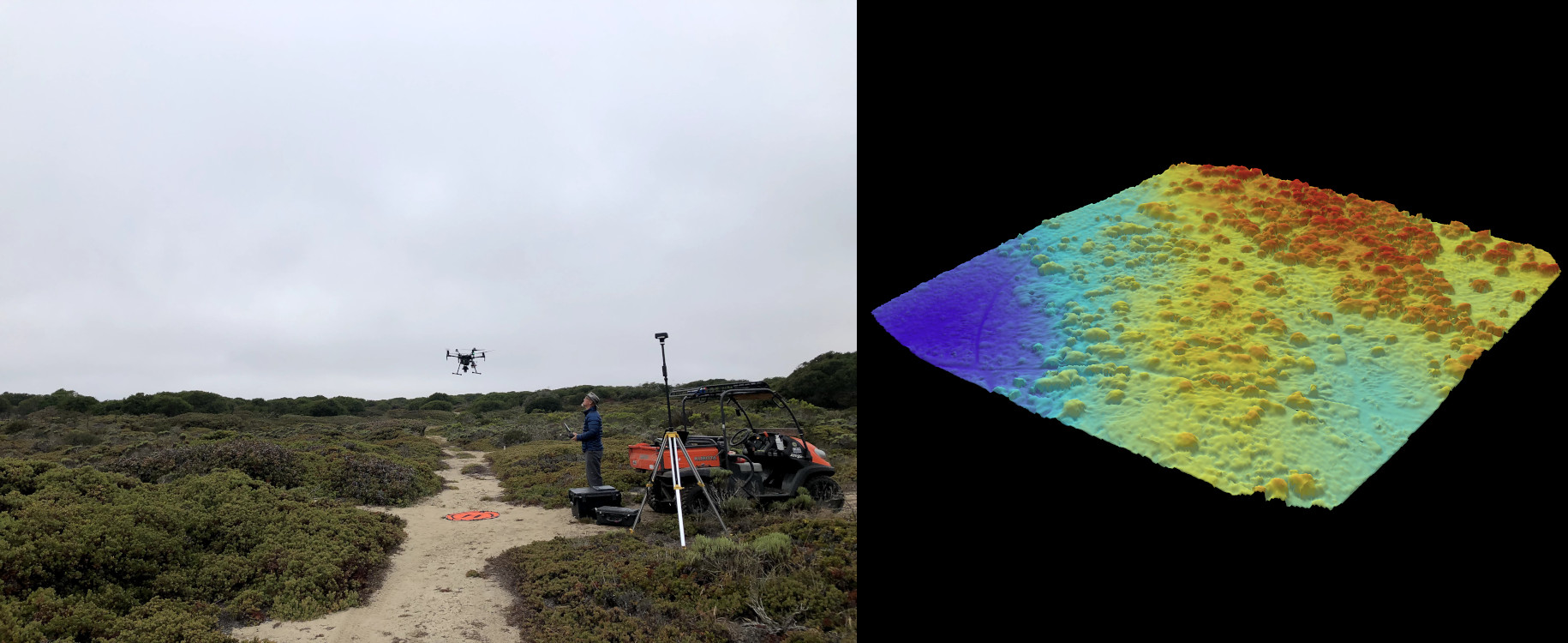

Detka is but one of the many researchers at UCSC, other UC campuses, and around the world who have had “lightbulb” moments grasping the promise of drones as transformative tools for research. Drones—also called uncrewed—or unmanned—aerial vehicles or UAVs—have potential applications in nearly every field of study, including performing surveys and collecting data for analyses of coastal and terrestrial ecosystems, animal populations, and remote archaeological sites; managing agriculture; creating bird’s eye cinematography; and, importantly, serving as a platform to drive the development of new technology, like remote sensing.

With the emerging new normal of California’s climate-change-fueled, supercharged drought and wildfire seasons, drones offer an unparalleled tool to facilitate field research aimed at assessing and informing measures to mitigate the resulting environmental effects. In addition, UC faculty and Monterey business leaders and entrepreneurs have also landed upon drones and drone-based technology as an up-and-coming, important economic opportunity for the Monterey Bay region. Predicted to grow to $90 billion by 2030, the global drone industry will demand skills in a workforce UC plans to foster, seeing the prospects as especially attractive for students with backgrounds traditionally underrepresented in scientific and engineering careers.

Lift off

With apologies in advance for the following alphabet soup, the drone-sporting people spotted by Detka that day belonged to the UC Drone Camp, a five-day training program that, according to its website, “covers everything you need to know to use drones for mapping and field data collection.” Run in its initial five years by a threesome of partners, including UCSC, UC Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR), and California State University, Monterey Bay, the Drone Camp, as of 2022, is now managed jointly by UCANR and a brand-new UCSC-based program called CITRIS Initiative for Drone Education and Research, or CIDER. CIDER, in turn, sprung from a mind meld of the UC Natural Reserve System’s Environmental and Information Technology Group and UC’s Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society, also known as “CITRIS and the Banatao Institute.” The high-profile CITRIS center, according to its website, aims to “leverage the research strengths of the University of California campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Merced, and Santa Cruz, and operate within the greater ecosystem of the University and the innovative and entrepreneurial spirit of Silicon Valley.” J. J. Garcia-Luna-Aceves, distinguished professor and chair of computer science and engineering, leads the UCSC arm of CITRIS.

Unique to the UCSC campus, CIDER officially launched in late 2021, with 20 undergraduate students accepted into its first Pilot-in-Training Mentorships in winter quarter 2022. The nine-week course of extramural instruction trains each student in the use of drone technology, including how to fly them, do photogrammetry and use software to create maps, and analyze imagery in Geographic Information Systems (GIS). In addition to providing a $600 stipend, the mentorship also helps students earn the Federal Aviation Administration license needed to fly drones and covers the cost of the test. Once licensed, the students become eligible for volunteer and paid opportunities with CIDER to fly drones and process drone-derived data in support of campus research and commercial contracts.

“Drones are incredibly cool and useful for all sorts of things,” said CIDER director and five-year drone aficionado Becca Fenwick. “There is a massive need to train students,” said Fenwick, who co-founded CIDER with Garcia-Luna-Aceves, CITRIS Executive Director Michael Matkin, and Justin Cummings, CIDER associate director (and current Santa Cruz city councilmember).

More than photos

The drone that replaced Detka’s GoPro-topped pool sweep does much more than take photographs. Detka created a computer model that uses artificial intelligence (AI) and drone images to locate and collect data on the specific plants he studies amongst the dense coastal shrubbery. “Just like Facebook uses AI algorithms to recognize friends’ faces, I’ve trained a computer model to recognize plants,” Detka said. “The drone sees things we can’t, like in the near infrared spectrum, which is really important for plant identification,” he said. “I can actually use the drone to identify shrub species and classify the health of plants in the landscape.”

Drones have indeed provided better and safer ways to conduct research, said Detka’s faculty adviser Gregory Gilbert, professor of environmental studies. “The data we collect characterizes the distribution and health of plants,” said Gilbert. “Sometimes this means traversing impenetrable scrublands, or the tops of tree canopies. We have ways to access these areas without drones, but they can be destructive and dangerous.”

Another budding drone researcher, Wendy Bragg, doctoral student in ecology and evolutionary biology, has also taken advantage of the accessibility drones provide. Following the extensive wildfires of fall 2020, heavy spring rains sent debris flowing down the Santa Lucia Mountains onto the beach and intertidal zone. In emergency mode, Bragg used a drone to quickly survey changes that might threaten the endangered black abalones she studies in difficult-to-access areas on the Big Sur coastline. “We went out right after the debris flows to see how things looked,” Bragg said.

When the drone footage identified areas with abalone likely buried in sediment, Bragg mobilized colleagues from MARINe (Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network, a consortium of organizations that monitor rocky intertidal ecosystems along the entire Pacific coast of North America) to help her unearth about 200 black abalones and escort them to UCSC’s Raimondi-Carr Lab to recover. Later that summer, she released her rescue abalone back into the wild in different—and hopefully safer—coastal sites.

Other UCSC researchers have used CIDER drones to study wildfire recovery in the forests of UCSC’s Big Creek Natural Reserve in Big Sur, Fenwick said, and the effects of drought on the campus’s Younger Lagoon Reserve, among other locations. She envisions the program eventually working with other large landowners, including the state, to study forest-scale wildfire patterns or survey widespread damage following an earthquake, as well as working with the agricultural industry.

Taking flight

The student pilots-in-training face a steep learning curve, Fenwick said, especially with the expensive drones equipped with the technology CITRIS/CIDER offers. And the Baskin School of Engineering connection to the program promises even further advances in drone capabilities. For example, Steve McGuire, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, is working with Gilbert and Detka on a new project to fly drones over the UCSC organic farm and Alan Chadwick Garden. The researchers plan to use “hyperspectral imagery” to try to predict and monitor the development of disease in crop plants.

In addition to surveying large fields much faster than humans on the ground, the drone data allows computer models—like the one used by Detka in his thesis research—to recognize changes in plants that indicate they might be sick or water-stressed. The sensing technology the team uses detects “a long-wave infrared that provides textual information about how the plants are absorbing the sunshine,” McGuire said. “This is taking pictures beyond the visual spectrum you can see with the human eye.”

Programs like CITRIS and CIDER are helping to put the Central Coast on the map as an emerging hub for drone development, said Josh Metz, co-founder with serial entrepreneur Chris Bley of the Monterey Bay business organization Drone, Automation & Robotics Technologies (DART). In its membership, DART includes industry, government, academic, and other drone operators, and researchers and developers working to advance the field. Metz, Bley, and other DART leaders host regional events, including a three-day symposium scheduled for November 2022, with the objective of bringing together individuals with diverse backgrounds but a shared interest in drones.

With its proximity to Silicon Valley and innovative research institutions; “wide open spaces” needed to fly; motivated public and private groups “focused on expanding economic opportunities”; and a growing number of companies setting up shop, the Monterey Bay is fast becoming a notable hub for drone research, Metz said. “Our hope is that with continued focus, coordination, and investment, the Monterey Bay region will become one of a growing number of national hotspots for drone-related innovation and economic development.”