In the heart

Preserving and sharing Watsonville's rich Filipino heritage

Juanita Sulay Wilson’s connection to the agricultural valley surrounding Watsonville lies deep in her sensory memory. “I love that feel of that valley and the beauty of it,” she said. “The richness of the soil is such that beautiful dark brown you don't see everywhere. Between that, and then the ocean smell, you come over the hill and you go, ‘I'm home.’"

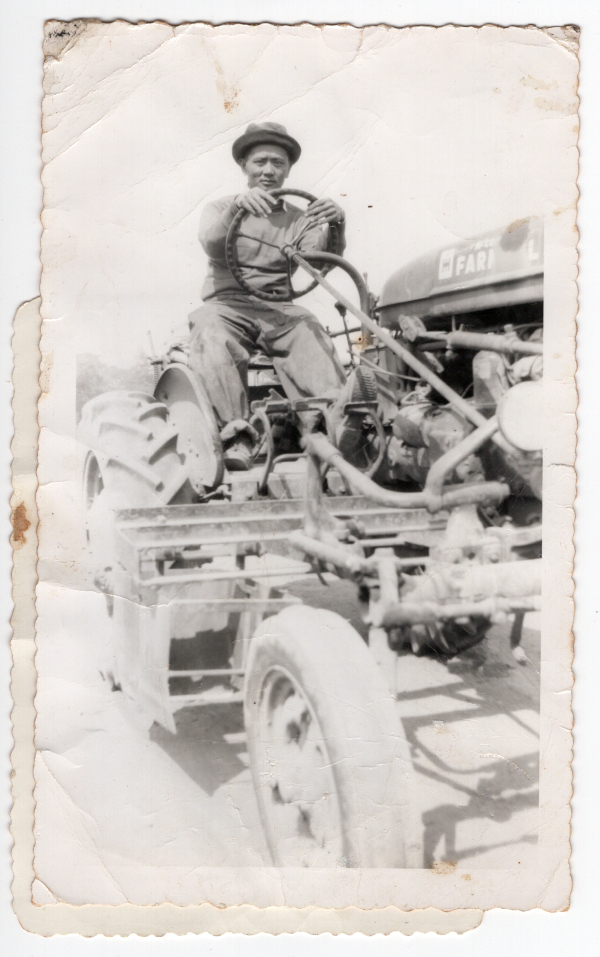

Sulay Wilson’s father, Mamerto “Max” Sulay, farmed the fertile Watsonville soil she describes. He was one of the tens of thousands of “manong,” the first generation of Filipinos who immigrated to the United States in the 1920s and 1930s to work as agricultural laborers. Her family’s story is among the dozens of oral histories now collected for “Watsonville is in the Heart” (WIITH), a jointly UC Santa Cruz– and community-driven “public history initiative” to preserve and share the rich heritage of the manong in the Pajaro Valley.

“We met this phenomenal group of community members who took it upon themselves to document their history. And we’re helping them do that,” said Associate Professor of Sociology Steve McKay, co-principal investigator of WIITH with Assistant Professor of History Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez. The two manage WIITH in partnership with Watsonville-born-and-raised community organizer—and manong descendant—Dioscoro “Roy” Recio, Jr.

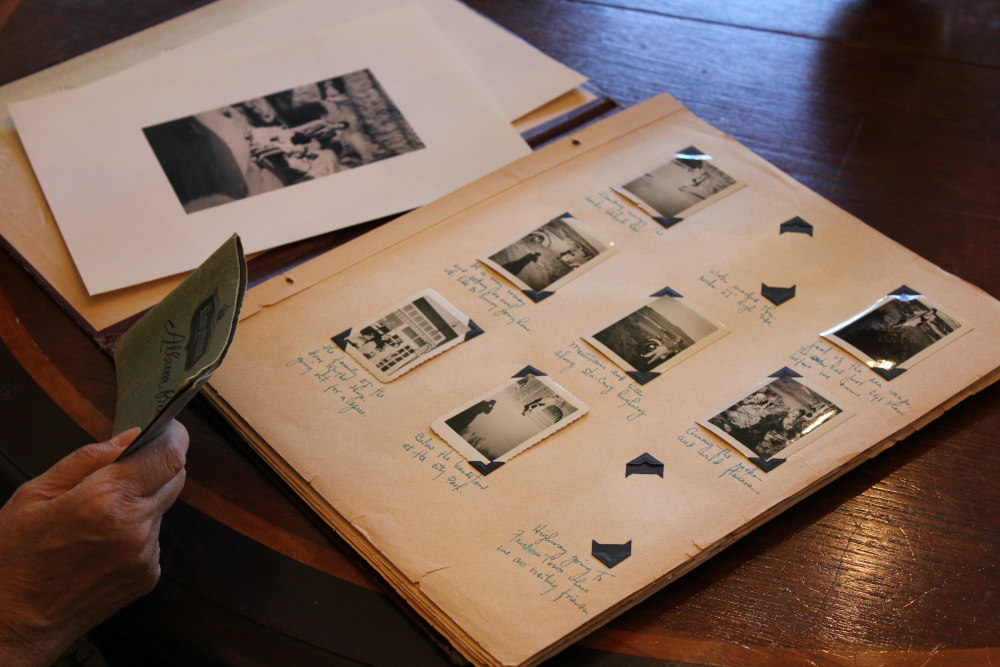

In addition to the project leads, the WIITH team consists of UCSC graduate and undergraduate students, as well as community research assistants. Their work includes recording oral histories from children of the manong, like Sulay Wilson, who are now in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, as well as scanning photographs and documents. These, along with transcripts of the oral histories, reside in a digital archive hosted on the Humanities Division server, with the actual recordings stored in the McHenry Library’s Special Collections and Archives.

Elder brothers

“Manong,” derived from the Spanish “hermano,” means “elder brother” in Ilokano, a language spoken in the northern Philippines from where many of these mostly male workers emigrated in the early 20th century. Traveling on a seasonal migration, the manong might have harvested sugarcane and pineapples in Hawai’i, picked lettuce, string beans, and strawberries in the Pajaro Valley, and canned salmon in Alaska. Eventually, however, some manong settled in Watsonville, forming tight community groups because of their shared heritage, but also because they were largely unwelcome in white areas and businesses.

Like many immigrant groups newly arrived in the United States, the manong were not just unwelcome, but actively subject to race-related violence. In January 1930, a deadly race riot targeting the manong rocked the city of Watsonville. For five days, mobs of hundreds of white men and boys terrorized and assaulted the Filipino community. During the turmoil, a shooting at a farmworker bunkhouse on the John Murphy ranch killed 22-year-old Fermin Tobera. The riot was “a pretty seminal moment in California history,” said McKay. “But the event is thinly documented, and never from the point of view of the Filipinos.”

By interviewing the living descendants of the manong about the riot and other events, the WIITH collaborators hope to better understand the Filipino immigrant experience by documenting the details of the farmworkers’ lives. The oral history narrators are “a graying population with a very unique perspective on immigrant life in the early 20th century,” said Gutierrez. There is a sense of urgency, she said, to capture these stories that can add depth and texture to the limited—and much biased—formal historical record of the time.

Community roots

Recio, whose father Dioscoro "Coro" Respino Recio, Sr., was a manong, planted the seeds of WIITH. After his parents died, Recio felt compelled to honor them in some way. “I wanted to make sure their stories and sacrifices were represented in a dignified manner,” he said, “and I found like-minded people who felt the same way.”

In 2019, Recio asked other Filipino Watsonville families to share their family photographs and history to produce a 2020 calendar. This undertaking—named The Tobera Project to honor the murdered Fermin Tobera—has since created a new calendar each year. “We’re building community with the common goal of sharing our humanity, culture, and experiences,” Recio said.

While Recio and his fellow manong descendants had ideas, passion, and momentum for their community project, they lacked a way to house the collected history and make it widely accessible. When McKay attended an exhibit Recio organized at Watsonville’s Freedom Branch Library, the two recognized the potential for a partnership, and joined forces with faculty and students at UCSC to create WIITH. The collaboration leverages the university’s resources to access archiving software, raise funds, and organize and promote events. Perhaps most importantly, the university provides a digital repository for the community’s history. “That’s one of the biggest things we can give—making sure there’s a home in perpetuity for these stories,” said Gutierrez.

Taking cues from Recio’s calendar work, the WIITH team organized an “archive drive” in Watsonville for Filipino community members to bring their family photographs and documents to be scanned on the spot for the archive. Led by the digital archive’s co-directors Meleia Simon-Reynolds (Ph.D. candidate, history) and Christina Ayson Plank (Ph.D. candidate, history of art and visual culture), the team has digitized more than 600 photos and documents and recorded oral history interviews with about 30 families. Ayson Plank also created an online exhibit that documents sites of manong labor and leisure in the region, and Simon-Reynolds is developing a K–12 educational curriculum associated with the archive. All this builds towards a Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History exhibit scheduled to open in 2024 that Ayson Plank will curate.

After learning about the project, Filipino and non-Filipino groups in other cities interested in pursuing similar efforts have contacted the team. “It’s exciting that this work can serve as a model for doing public history and scholarship,” said McKay. By making local history accessible, he said, WIITH helps fulfill the university’s mission as a public institution to benefit the broader community.

Seeing connections

The project has also highlighted important connections between the past and present, McKay said, with the 1930 Watsonville riot foreshadowing the spike in anti-Asian rhetoric and targeted attacks against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Understanding the past helps put our present in context,” he said. “What happened in 1930s Watsonville around the race riot teaches us a lot about racism today.”

Rick Baldoz, former associate professor of sociology and comparative American studies at Oberlin College (now at Brown University), made the same connection in a Washington Post op-ed, pointing out that “anti-Asian sentiment is deeply rooted in American history.” The Watsonville riot is just one well-known example of a wave of anti-Filipino violence that occurred during that period, as Baldoz details in The Third Asiatic Invasion: Empire and Migration in Filipino America 1898–1946 (NYU Press, 2011). “Despite all the hostility, these immigrant pioneers really fought to carve out a space for themselves in an American society that wasn’t very welcoming,” said Baldoz, who has consulted with WIITH. The project, he said, “is really attentive to the important role of ordinary people in California’s development and growth as an economic powerhouse.”

Both WIITH team members and the project’s Filipino American participants described the experience of hearing and sharing the community’s stories as moving and meaningful. Beyond recounting discrimination and struggle, the oral histories and photographs paint compelling portraits of family life, festive community gatherings, and the resilience of a generation striving to sow the seeds of opportunity for their children. “It's important to remember who came before us and the sacrifices they made, what they had to go through,” said Sulay Wilson. “I was always told, ‘Never forget where you come from.’ And I really try hard to remember that.”