Doublespeak

The mental gymnastics of speaking another language requires using a new sound system while suppressing the dominant one of your first language. How people achieve this feat—and its linguistic, social, and cognitive consequences—centers the research of Mark Amengual, associate professor of applied linguistics and director of Spanish Studies. “I’ve always been intrigued by how seamlessly bilinguals switch between languages,” said Amengual, himself multilingual, speaking English, Spanish, and Catalan.

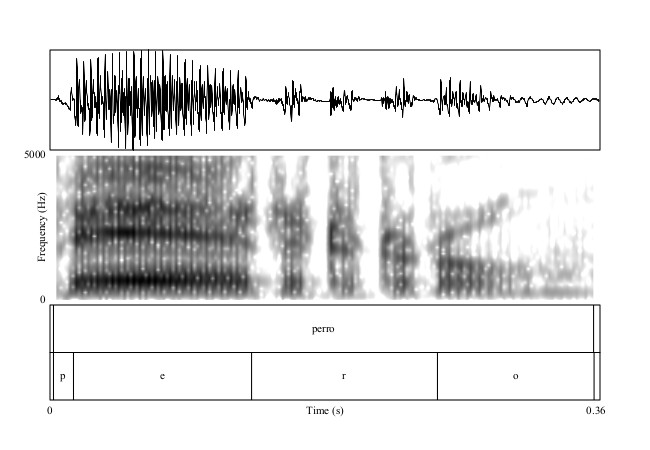

In the UCSC Bilingualism Research Laboratory he directs, Amengual analyzes the acoustic profiles of multi-lingual speech collected under controlled experimental conditions. In one study, for example, Amengual compared two groups of Latino Spanish-English bilinguals—one speaking Spanish at home and not English until starting school and the other exposed to both languages from birth—with a third group of bilinguals who grew up English-speaking and then acquired Spanish by studying it in college. It turns out the degree of exposure to each language in the formative, early years of life has a persistent effect, influencing adult speech acoustics in a quantifiable way.

To get a fuller picture of “what bilingualism is all about,” Amengual also studies speech perception among Indigenous bilingual populations in Mexico who speak Spanish and an endangered language, Hñäñho. “Perception and production,” said Amengual, “are two sides of the same coin.”

—Elizabeth Devitt