Documenting reality

Female filmmakers aspire to move the field—and the world

Besides banana slugs, UC Santa Cruz sports a healthy population of another amazing creature. Amidst the towering redwoods on UCSC’s verdant campus, there also roams a thriving colony of world-class women filmmakers. This unusual cluster of still unfortunately rare—but notably spectacular—individuals includes many who have achieved broad acclaim with their groundbreaking documentary films addressing a broad range of topics, from long-forgotten history to environmental injustice. While men still dominate the world of documentary filmmaking (and all filmmaking), you wouldn’t know it by looking at the makeup of the collective UCSC visual arts departments.

A diverse group of women from all walks of life now account for more than 65% of the Arts Division’s faculty, according to Dean of the Arts Celine Parreñas Shimizu. And many of these women are engaged in practicing, teaching, and shaping the evolving tenets of documentary filmmaking. “All of these filmmakers, who are so renowned in their fields, define their service to the university, not in terms of their fame, but in the way they are training the next generation of filmmakers,” said Shimizu, herself a documentary filmmaker.

Among these women are Irene Lusztig, Jennifer Maytorena Taylor, and Elizabeth Stephens. As stand-out filmmakers, artists, and educators, Lustig, Maytorena Taylor, and Stephens are shaping important discussions about our society, said Robb Moss, professor of visual and environmental studies at Harvard University. “Each has affixed themselves to the big, sprawling, complicated issues of our day,” said Moss, who is also a documentary filmmaker. “They’ve all done extraordinary work researching, exploring, and trying to make sense of the things that are most fascinating and sometimes troubling about our society.”

Although their backgrounds and work differ substantially, all three women share a strong commitment to ethical and inclusive filmmaking. We spoke with each about how they became documentary filmmakers, their work, and their efforts to change the field for the better.

Archival passion

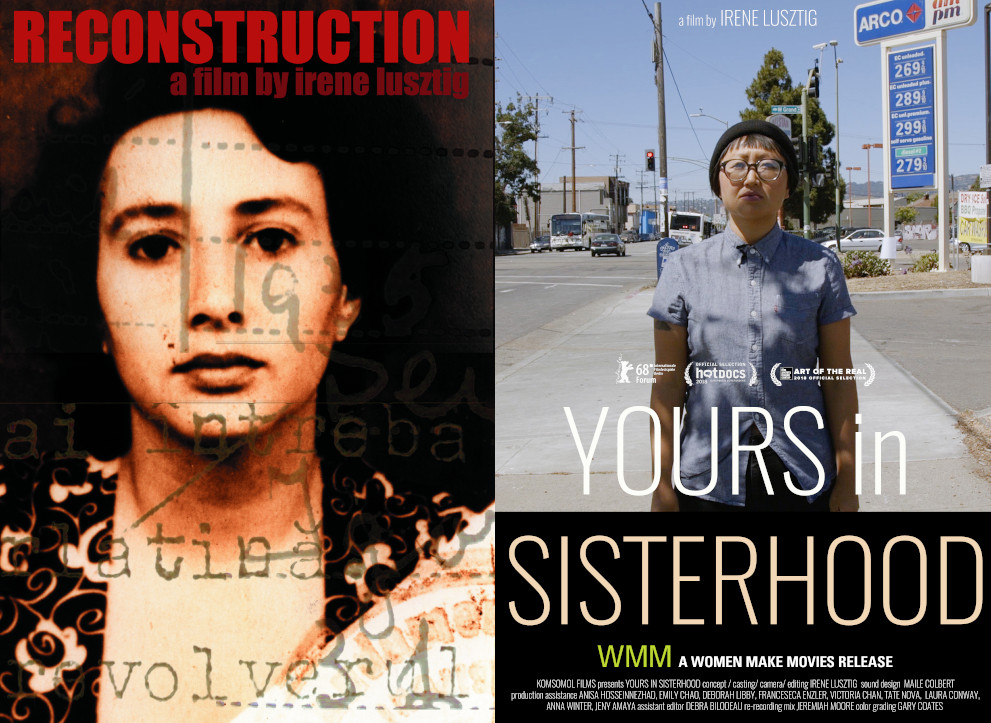

A filmmaker and visual artist with a passion for archival research, Professor of Film and Digital Media Lusztig finds stories in long-forgotten historical archives and breathes new life into them using experimental documentary techniques. Much of her work focuses on the history of women and perceptions of women’s bodies, including her latest film Yours in Sisterhood. The film, which premiered in 2018, explores the past, present, and future of feminism inspired, as described on the film’s website, “by the breadth and complexity of letters sent in the 1970s to the editor of Ms., America’s first mainstream feminist magazine.” Lusztig, who joined the UCSC faculty in 2008, currently serves as the director of the Center for Documentary Arts and Research (CDAR).

How did you get into filmmaking? I went to college wanting to be a painter and took a film course by accident. But as soon as I was in the class, I understood right away it was bringing together many different things I was excited about. I knew I was a visual thinker and wanted to make visual work, but I also love to research. It just felt like a way to explore the world that could bring all the things I was excited about together. I graduated in the mid-‘90s and then immediately started working on Reconstruction (2001), my first feature-length film.

The film was about my family, a wonderful place for young filmmakers to start. In 1959, my mom’s mom participated in a bank robbery in Bucharest, Romania. The interesting thing is that, after she was arrested and convicted, she “starred” in a bizarre propaganda film about the bank heist produced by the Romanian state. To make the film, she, her husband, and the other men involved were basically forced to re-enact an “official” version of what happened. And I was able to find that film with my grandmother in it, performing as herself. I think my way of investigating the world came out of the experience of making that film. I still encourage my students to make films about stuff that's close to them.

How do you approach filmmaking? I allow myself a very long research process—it can take years before I start filming. This is different from how much of the film industry operates. I'm really interested in history and people's engagement with history. Questions about memory and history shape all my work.

How are you influencing the filmmaking scene at UCSC? The film industry still has a long way to go in terms of really representing the full breadth of different lived experiences. But our students are telling stories that represent all those perspectives. We have a lot of first-gen students, a lot of Hispanic students, a lot of students from immigrant families—basically, a lot of students with quite diverse life experiences. Those of us who get to work with these students are nurturing new voices that will start telling new kinds of stories and representing new kinds of perspectives. Much of the work I do is thinking about how to support these students and give them the tools, confidence, and critical thinking skills they need to go out in the world and create new kinds of films.

People-centered

The films of Associate Professor Jennifer Maytorena Taylor center around people, communities, and cultures that have been overlooked by mainstream society. Prior to coming to UCSC in 2012, she worked at the San Francisco–based public media station KQED where she produced award-winning documentaries on topics ranging from gentrification in two diverse working-class communities in the San Francisco Bay Area (Home Front, 2001) to Puerto Rican American Muslim hip-hop culture (New Muslim Cool, 2009). Born in Los Angeles and fluent in Spanish and Portuguese, Maytorena Taylor’s mixed heritage includes Mexican, Sicilian, and Irish/English. She credits her diverse background with driving her to seek out the stories of those with similarly complex identities.

How did you get into filmmaking? I originally wanted to be a dancer, but I badly injured both knees and had to stop dancing. Eventually, I got interested in the way mass media was serving as a platform for social change and social movements, in the different ways that movies, TV, and pop music were enabling essential conversations about social issues through fun and accessible formats. So, I started making short videos and films back in the 1990s when you would record things on videotape. My first feature documentary, Paulina, was a collaborative effort with filmmaker Vicky Funari. It first premiered in Havana in December 1997 and then in the U.S. at Sundance in January. Set in Mexico, it was a Spanish-language film, with English subtitles, which told the life story of Paulina, a maid originally from Veracruz. Much of it revolved around sexual abuse and assault. We—unusually and experimental at the time, but now more accepted—included Paulina in the editing process, to ensure that her image as a resilient, creative woman, a survivor, was reflected in the final film. It was a labor of love that so often characterizes independent documentary films, and it made me decide I wanted to work in documentary filmmaking full time.

How do you approach filmmaking? I strongly believe in stories that are very, very specific—paradoxically, the more specific the story, the more potentially universal it will be. And that's why my production company is called Specific Pictures. I'm really interested in how big structural issues get expressed through day-to-day life, and through encounters that may seem insignificant, but when you put them in a film, they can become significant. I'm also interested in communities, people, and places, which have been mischaracterized or simply ignored by mass media and bringing others into awareness of those communities, but through perspectives that resonate with the folks inside them. Everyone, me included, goes into places with fixed ideas, assumptions, presuppositions, and hypotheses. My job is to test those and be willing to be proven wrong. It's also crucial that as you make media of any kind, whether it's a documentary, book, or a written piece, you do so by engaging the community it’s about. You don't just helicopter in, make it, and leave. The world is now catching up with us—this mode of filmmaking is now being recognized on a more mainstream level.

How are you influencing the documentary filmmaking scene at UCSC? By incorporating my ongoing active practice as a documentary filmmaker, making work for national outlets like PBS, into my teaching and role as director of the Social Documentation M.F.A. program. I consistently bring new lessons learned through my own work in the evolving field of documentary film, and my extensive relationships with organizations like Sundance Institute, back into the classroom. There's a growing awareness that mass media culture has done a generally terrible job of representing communities that have been systematically pushed out. A whole cultural change needs to take place in representational media, and we see ourselves as the vanguard of that.

Nature lovers

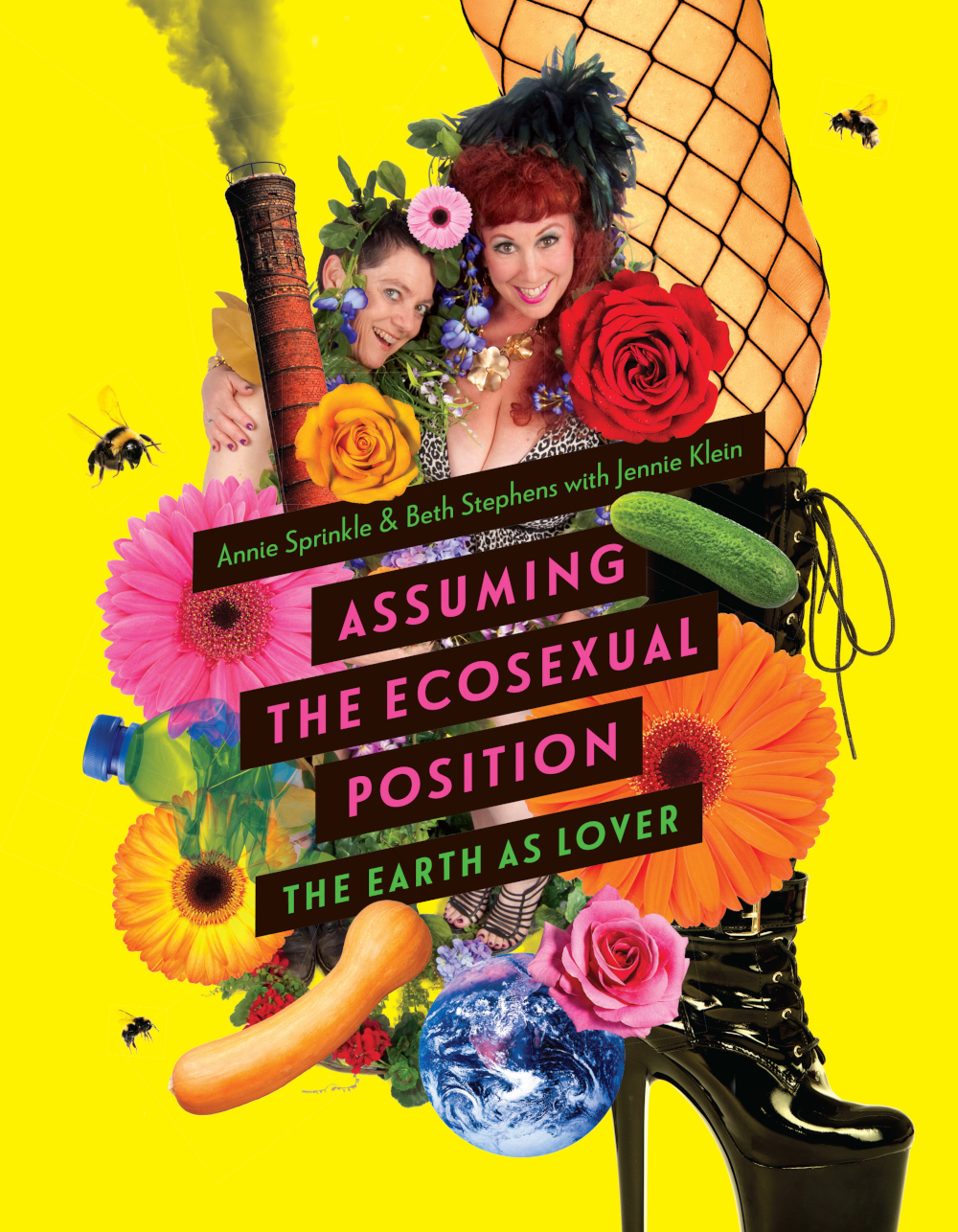

Filmmaker, performance artist, author, and activist, Professor of Art Beth Stephens is a self-described “fiercely devoted lover of the Earth.” This devotion is amply evident in all her work, whatever form it takes, which has included films, sculptures, writings, and live performances. In all of it, she tells stories about her love of nature, typically through a queer lens. In 2008, Stephens and her wife, UCSC staff member Annie Sprinkle, held a ceremony in the Santa Cruz Mountains in which they married the Earth, kicking off what has since become known as the “ecosexuality” movement. She and Sprinkle subsequently coauthored the book Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth as Lover (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), which explores the origins of the movement as well as their partnership. Stephens joined the UCSC faculty in 1993 and is the executive director and co-founder of the university’s E.A.R.T.H. Lab (E.A.R.T.H = Environmental Art, Research, Theory, and Happenings); Sprinkle, her co-founder, serves as the lab’s director of research.

How did you get into filmmaking? I grew up in West Virginia and I realized on a trip home that the mountains there were being destroyed in a heartbreaking way. I started investigating and learned about this horrific form of coal mining called mountaintop removal. I thought, wow, everybody needs to know about this because it's awful. I thought a film would be one of the better ways to broadcast this environmental disaster, so I made Goodbye Gauley Mountain (2015) with Annie Sprinkle, my partner. It's probably the first queer environmental documentary ever made.

How do you approach filmmaking? My partner and I created Ecosexuality, a conceptual art movement based on loving the Earth and shifting the metaphor from ‘Earth as mother’ to ‘Earth as lover.’ The way I go about making a film is wrapped up in ecosexuality. With Annie, I've made a film about the Earth and another about water (Water Makes Us Wet, 2017). Our next one is about fire. I’m an untrained filmmaker, and my approach is really one of curiosity. I don't sit down and write a script. Ideas come and then we pursue them and see where they go.

How are you influencing the documentary filmmaking scene at UCSC? When I started teaching here, I never imagined that Annie and I would be the movers and shakers of the ecosexual movement. Most universities wouldn't allow me to do that, and I probably would have been fired. I really love teaching and I find my students very inspiring. My goal is to help them learn how to be creative, so that they can engage in life in a creative improvisational way, especially in the face of climate change. Thinking creatively and being able to improvise are especially useful tools because the standard ways of how we've been facing the future might not serve us so well anymore.