Creature features

A fish—a long, skinny one—out of water

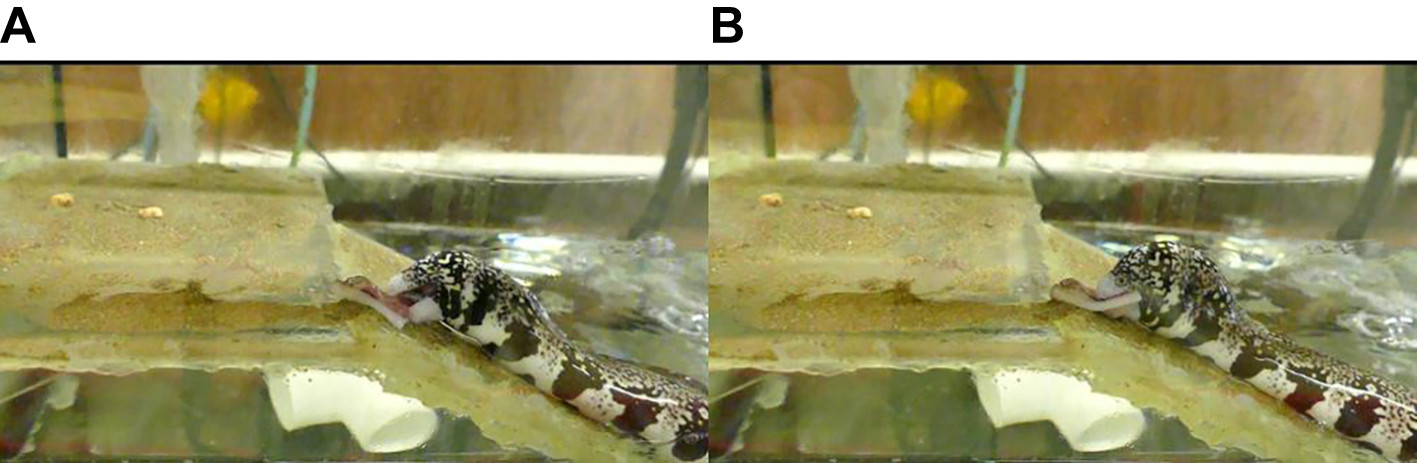

Under the glare of bright lights, the pattern-stamped skin of a snowflake moray eel shines as it serpentines around a saltwater tank. Video cameras are rolling, ready to capture the moment the eel hauls itself out of the water, slithers up a sandy ramp, and snatches a bit of squid on dry “land.” Once the eel makes its move, it takes less than a minute to document an evolutionary adaptation millions of years in the making: unlike any other fish, some moray eels don’t need water to get a meal.

Catching that feeding behavior on camera took more than six years, seven eels, and an ever-changing roster of ardent student assistants under the direction of Rita Mehta. A professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, Mehta studies the diversity of form and function in animals with an elongated body plan, especially eels. “The way an animal is shaped has a really large effect on what they can eat, how they behave, and the types of environments they can take advantage of,” said Mehta. “Morays are fascinating because their adaptations are so extreme.”

Double take

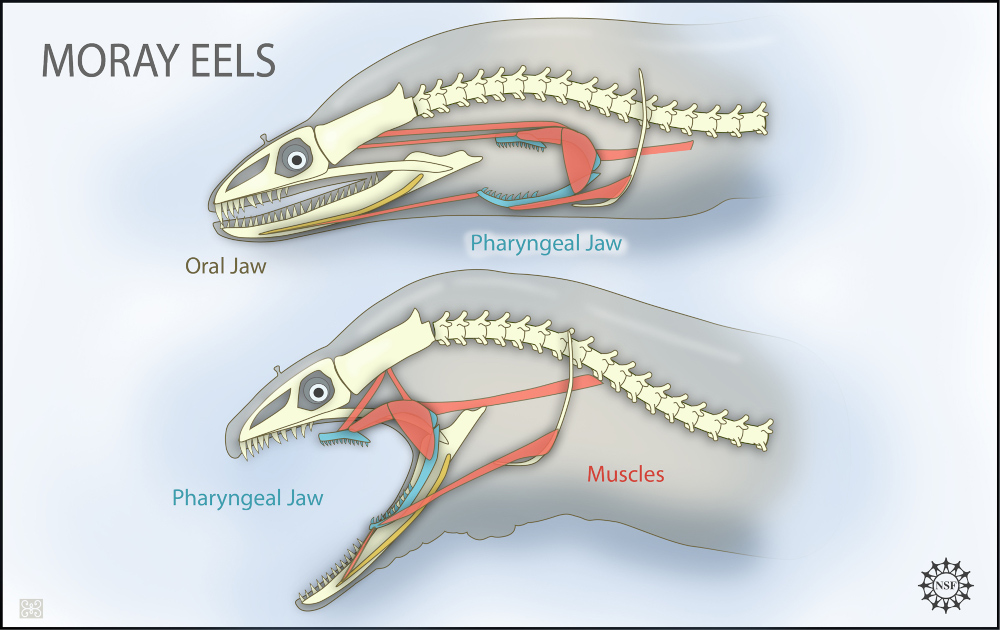

Morays manage to take prey without the benefit of water because their second set of jaws function like something straight out of a sci-fi movie (think Alien). Positioned behind a “first” jaw already full of sharp, backward-pointing teeth, the second “pharyngeal jaw” lunges forward into the mouth and drags food down the throat. Although the anatomy of this double-jaw system was described decades ago, Mehta was the first to video the moray’s double jaws in action, as a postdoc in Professor of Evolution and Ecology Peter Wainwright’s “fish lab” at UC Davis. Morays turn out to be an extreme example of evolutionary adaption—-and, therefore, particularly interesting to functional morphologists like Mehta and Wainwright because unusual behaviors are often linked with extreme adaptations.

The Wainwright Lab’s research focuses on the feeding mechanisms of fish. “We look at the ways evolution tweaks fish anatomy to produce all this ecological diversity,” said Wainwright, a biologist who specializes in reef fish. He likened the research process to taking apart bicycles: “What is it about the build of a mountain bike that makes it better for jumping up and down hills than a road bike with its goofy handlebars?”

Although pharyngeal jaws are common in bony fishes, most fish are suction feeders and use their mouths to generate a wave of water to suck in prey. Even the mudskipper, a fish long known to take prey on land, carries water in its mouth to use that technique on terra firma. And, in most bony fishes, the second set of jaws tucks within the oral cavity. But the drastically modified two-jaw system of morays allows them to eat big prey that are quite hard to swallow—-particularly without water.

To see how the mechanism worked from inside, Mehta teamed up with Rachel Pollard, a veterinary radiologist at UC Davis who specialized in swallowing disorders of animals. “It was a creative process,” said Pollard, now retired, as she recalled how an enthusiastic technician, Candi Stafford, carried out their painstaking plan. They had to be fast enough to take x-rays while the hopefully hungry eels ate dead goldfish into which the researchers had injected radiodense iodine. “Remarkably, it worked,” Pollard said, although not exactly as planned. It turned out the injected dye was hard to see, but they could watch the pharyngeal jaws in action by tracking the swallowed fish by their bones and the air in their swim bladders.

Body building

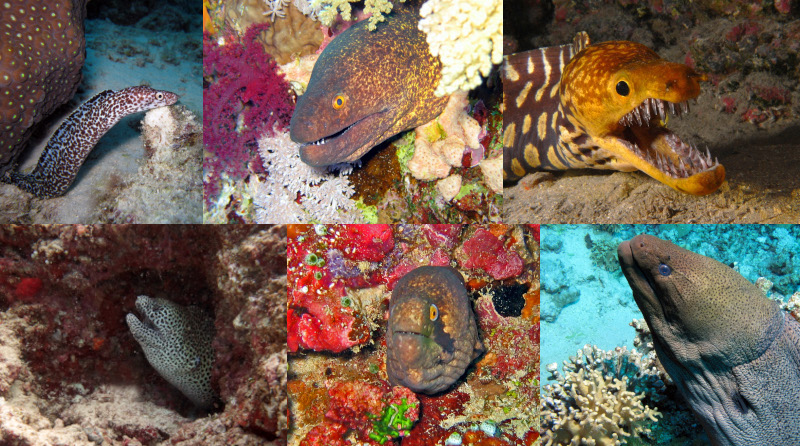

But there is more to morays than their monstrous mouths. These eels belong to the Muraenidae family, in the larger order of Anguilliformes, which includes more than 800 eel species found worldwide. Although eels all have similar stretched-out physiques, the 200-plus species of morays display amazing diversity in the way they’re put together—from the number of vertebrae in their spine to the shape of their skull.

Mehta’s research showed how the long body plan of morays evolved differently than in other eels. The three ways to extend a fish spine are: by adding more vertebrae at the front (pre-caudal) part of the spine, adding more at the tail (caudal) end, or making each vertebra longer. Working with long-time collaborator Andrea Ward, professor of biology at Adelphi University in New York, Mehta surveyed vertebral patterns in 54 different eel taxa. When they compared the vertebral patterns among three major eel families, those from the moray group added more vertebrae in the caudal region—-a longer tail—-while the other two major eel groups added equal numbers of vertebrae in both spinal regions.

Vertebral patterns affect how an eel moves and correlate with some behavioral differences among eels. For example, Mehta observed that the extra caudal vertebrae gave morays enough length to tie an overhand knot with its body, and then use it as an anchor to help capture prey, or to slip it up their body to entrap prey.

Eels’ meals

The fact that morays can ingest large prey, in one mouthful, puts them among the top predators in their environments. Yet little was known about the moray diet or how the eels impacted their ecosystems, said Mehta. Key predators affect the abundance and distribution of their prey, which, in turn, influences the rest of the food chain. So one of the first steps to figure out the moray’s role was to find out what they ate.

To learn more about their menu, Mehta searched scientific databases for reports on moray prey. She visited museums where, along with her students, they extracted and catalogued the stomach contents of preserved eel specimens. And in the field, Mehta trapped morays in Caribbean and California waters. Using a technique learned during her graduate studies on snakes, she anesthetized the eels and then massaged their stomach contents upward to extract the prey from their mouths, a method that allows her to study the eels without causing them harm. Along with the dietary data, she recorded a broad set of measurements including skull size, jaw length, and number of teeth.

These investigations showed that morays eat a diverse diet of small fish, octopus, shrimp, and hard-shelled prey such as mollusks and crabs. More intriguing to Mehta, was that different species showed distinct preferences for fish (piscivory) or hard-shelled prey (durophagy). What made a moray want fish, she wondered, rather than crab? While morphological differences between skulls and teeth showed that piscivores had sharper teeth and longer skulls, Mehta found other skull changes were also important. For instance, durophagous eels had skulls that supported the attachment of thicker cheek muscles, the better to bite harder.

The eels' dietary choices also correlated with differences in their organ systems. In a series of dissections, Samantha Gartner, a former UCSC undergraduate now studying fish morphology at the University of Chicago, compared organ placement and size among nine species of moray eels. Among the differences she found, the hard-shelled prey eaters had smaller hearts, possibly because they don’t have to swim so much to catch their prey. Mehta also expected to find smaller stomachs in durophagous eels, because they digest fragments of food instead of whole fish. But this wasn’t the case—at the microscopic level, Mehta saw that hard-shell–eating eels had thicker stomach walls, perhaps to protect them from the shards of shells. “There’s so much incredible diversity out there,” said Mehta. “We’ve only just begun to tap into diet and morphology.”

More questions

California has only one species of moray, the aptly named California moray. Gymnothorax mordax lives in kelp forests and rocky shorelines near Santa Catalina Island, southwest of Los Angeles (and elsewhere down the Pacific coast and around some Pacific islands). But morays are not part of a commercial fishery, so the eels had received little scientific attention. In fact, no one thought many morays were in the area until Mehta began studying them in 2010. With then–graduate student Benjamin Higgins (Ph.D. ‘18; now chief scientist with Kokua Services, a cannabis cultivation company in Olympia, WA), Mehta trapped, examined, and tagged 462 morays within an area called Two Harbors in just a few weeks. Not only did their survey find more morays than expected, but throughout the years that Mehta and her team have returned to their field sites, they’ve repeatedly trapped many eels in the same location. The tendency to stay in one area, called site fidelity, suggested the eels’ feeding preferences might be playing a big role in the local ecosystem.

In 2015, Mehta and Higgins expanded their Two Harbors study to the Blue Cavern Onshore State Marine Conservation Area on the leeward side of Santa Catalina Island, a “no take” marine protected area (MPA) where fish cannot be removed for any reason. Here, joined by UCSC doctoral student Katherine Dale and undergraduate researchers, they trapped and measured the weight, size, age, and body condition of 1,736 eels over the next three years. Their results showed that more eels, and larger and older ones, lived inside the MPA than outside it. Morays outside the MPA ate a greater variety of prey, while eels inside had a higher rate of cannibalism. Those results generated more questions: What did it mean for the commercially important kelp bass to live with a bigger, older eel population? Did the morays prefer different sizes of kelp bass? Did preferences change with prey abundance? As Mehta and her students have continued studying these morays, their findings are providing insights that could help improve MPA management.

Although Mehta has specialized in morays, her work in the eel realm extends more broadly. In one large study, she and Ward analyzed how various types of eels move in the water and across different substrates and inclines. “We’re trying to understand how these animals use their bodies to propel themselves on land,” said Ward, whose work focuses on American eels, an endangered fish that migrates between saltwater and fresh-water. Learning how eels maneuver most efficiently could help boost their declining populations by informing the design of more eel-friendly passages across the dams that interrupt their migration routes to inland freshwater habitats.

Moray amore

Mehta’s lab research, museum work, comparative studies, and field ecology, all aim to pull together the ecology of morays, said Elizabeth Dumont, an evolutionary biologist who studies form and function in bats. Dumont, UC Merced dean of the School of Natural Sciences, has been a collegial mentor for Mehta since they met at an engineering workshop more than a decade ago. “You pick away on the ecology, you pick away on the evolution, and then at some point you finally have enough to start seeing the picture of how it all fits,” Dumont said. “Then you can start asking the bigger evolutionary questions, like why are there so many long, skinny fishes?” With the biodiversity crisis worsening across the globe, these questions matter, Dumont said. “If we don't understand how things evolved and got here, we can’t make good predictions about the future.”

In pursuit of answers to the myriad questions that continue to arise as she learns more about her outwardly fierce but truly quite shy research subjects, Mehta is undeniably committed to morays. “Everything about them is a surprise,” she said. And it’s clear to her that once acquainted with these captivating creatures, other people soon feel the same. “When undergraduates visit my lab and see what I’m working on,” Mehta said, “they quickly become fascinated.”