BRIEF inquiries

Music

Compose yourself

Professor David Evan Jones discovered traditional Korean music in 1996, at the first of now six UC Santa Cruz Pacific Rim Music Festivals, the last held in 2017. Organized by Professor Hi Kyung Kim, Jones's Music Department colleague and fellow music theorist and composer, the festivals bring to campus musicians from Japan, Taiwan, Australia, and Korea, among other countries, to share and perform new music. It was there, Jones said, that he began to form lasting friendships with a community of Korean musicians, leading to the professional premiere of his chamber opera, Bardos, in downtown Seoul.

That first trip to Korea in 2004, Jones said, sparked his interest in composing music for traditional Korean instruments, including the daegeum, a long bamboo flute, and the gayageum, a 12-stringed zither. “I have technical and theoretical curiosities about the ways music can be and is put together in different cultures,” said Jones, who also creates music compositions using computers and unconventional sources such as audio from news broadcasts.

Writing music for Korean instruments required multiple attempts to get right, Jones said. Ultimately, though, he said he was very pleased with the 2017 performances in New York, Santa Cruz, Berkeley, and Seoul of his Dreams of Falling for a full Korean orchestra. His favorite instrument? The gayageum. “It makes the most beautiful sound in the world,” Jones said.

—Annie Melchor

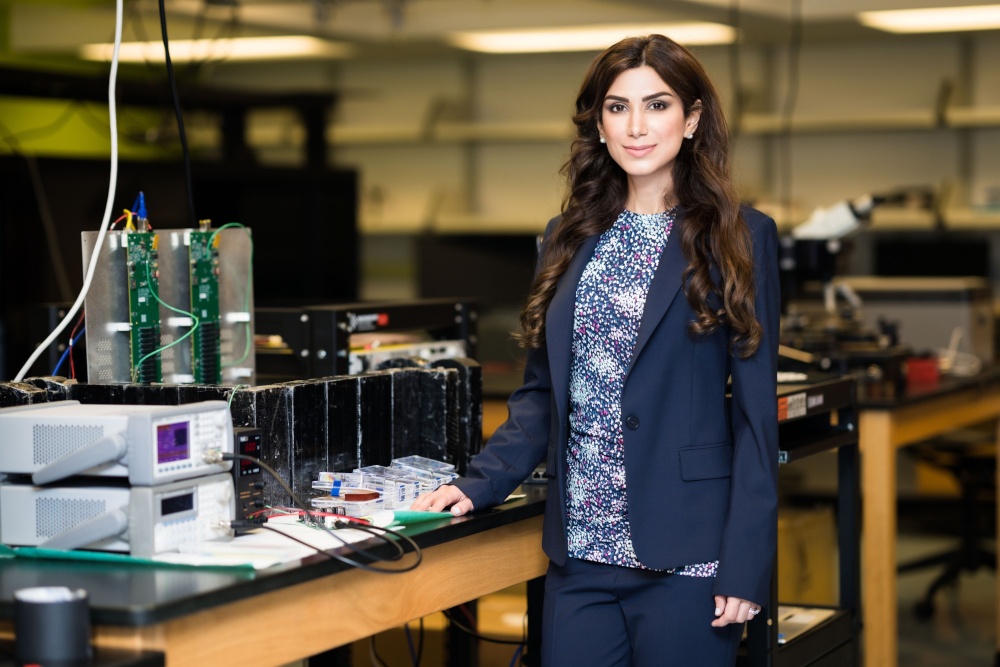

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Reimagining imaging

Cancer and plant growth might seem quite different subjects, but the research of Assistant Professor Shiva Abbaszadeh has common roots. In her Radiological Instrumentation Laboratory, Abbaszadeh and her students work to develop tools for imaging and sensing low levels of radiation, with potential applications ranging from healthcare to sustainable energy. “There is no similar facility in a research university for the type of detector we are fabricating,” said Abbaszadeh. “Maybe one or two companies and one or two national labs do similar work.”

Much of the lab’s efforts focus on improving conventional medical imaging technologies like positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT). Abbaszadeh’s $2.3 million in National Institutes of Health grants support the development of highly accurate, low-radiation systems customized specifically for medical imaging of the brain and lymph nodes in the head and neck.

An additional 2021 Department of Energy grant provides nearly $2 million over three years to develop—with academic collaborators including Weixin Cheng, professor and chair of environmental studies—a low-cost, combined PET/CT-based system for imaging plant-soil interactions. The newly funded research aims to track the movement of carbon between soil and roots, heretofore possible only by disturbing the experiments. “This technology will help us answer questions we couldn’t answer before because we didn’t have tools to investigate them,” said Abbaszadeh.

—Erin Malsbury

Ocean Sciences

Helping kelp

In 2014, kelp, an iconic feature of coastal California, started dying—and kept dying. Per a UC Santa Cruz-led study published in 2021, the once lush forests of this bulb-topped, giant algae off the California coast had, by 2019, receded by more than 95%. Taking their place? A barren sea floor crawling with spiny sea urchins.

Historical records indicate that kelp abundance cycles with environmental conditions, typically declining as coastal waters warm. But the latest die-off appears poised for persistence. An atypically dogged warm water mass lasting from 2014 to 2016 (nicknamed “The Blob”) likely initiated the kelp decline. But then, a strong El Niño followed. The unusually extended warming exacerbated disease-related die-offs of the sea stars that eat urchins. Not surprisingly, the numbers of purple sea urchins—the voracious primary predators of kelp—exploded. How long this possibly climate change-related ecological upset will last is unclear. “I think the kelp will return,” said Professor Peter Raimondi, who co-leads the coastal ecosystem-focused Raimondi-Carr Lab with Professor Mark Carr. “The more important question is will such die-offs become more common.”

In a step towards potentially helping kelp to recover, Raimondi’s genetics-based research has identified kelp subpopulations adapted to thrive at different water temperatures. If coastal policy called for human intervention, Raimondi said, “You could theoretically restore kelp populations from a “seed bank” with stock adapted to current or expected temperature ranges.”

—Bethany Augliere

Computational Media

Playing for real

Kate Ringland can spend hours each day on Twitter “posting tons of nonsense” while engaging with accounts dedicated to the popular Korean boy band BTS. But for Assistant Professor Ringland, a long-time member of ARMY, the official—40 million-strong—fandom of BTS, scrolling through the memes isn’t just for fun. She’s making observations, taking notes, and asking questions, all part of her research to explain and characterize how playful online communities like ARMY enable acts of care and promote social activism.

Contrary to the craziness some might imagine happening in a stereotypical fandom of rabid teen girls, real mental health support occurs in ARMY, Ringland said. With outcomes like those achieved in, for example, a depression support group, online interactions amongst ARMY members have the potential to provide substantial benefit. On Ringland’s Twitter account where she shares content for disabled ARMY members, as many as half a million people have viewed her posts. “That kind of reach is unheard of in other support settings,” she said.

By studying the ways play-based online communities support marginalized individuals, especially people with disabilities, Ringland hopes to better understand what it means to be social. “There are really positive, important caring activities happening in these online spaces,” Ringland said. “We shouldn’t disregard them.”

—Emily Harwitz

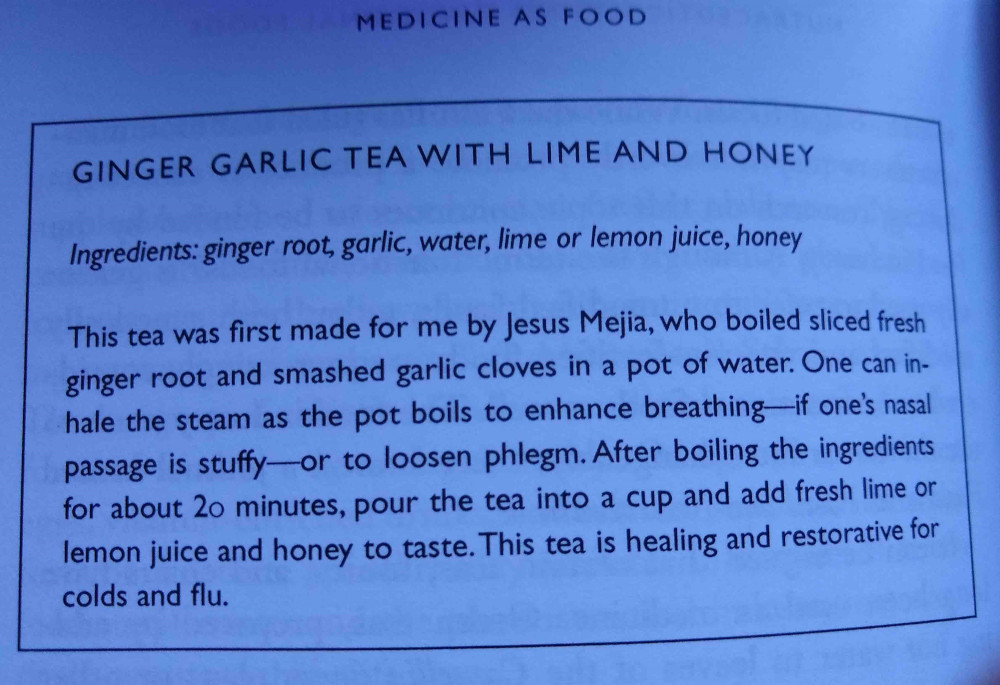

Anthropology

Eat your medicine

When Professor Nancy N. Chen feels a cold coming on, she prepares a pot of fresh garlic, ginger, honey, and lemon tea. Making sure to inhale the steam from the smashed—not chopped—garlic, she drinks the brew all day. For Chen, a medical anthropologist, food stands at the frontline of healing and she “eats her medicine.”

How food, medicine, and culture intersect animates Chen’s research. The notion that food can heal is not new—“These concepts have been around for centuries,” Chen said. Building on this knowledge, Chen partnered with Kellee Matsushita-Tseng, assistant manager of the UCSC farm garden, to mentor and support students in the Global and Community Health Wellbeing Fellows program while they tend the Center for Agroecology’s newly revitalized Community Herb Garden. The work, Chen said, aims to reconnect BIPOC students to their ancestral heritages via food and herbal cultivation, as well as through “active engagement” with the soil, each other, and local communities.

Chen’s scholarship facilitates her role, since 2018, as the Division of Social Sciences’ associate dean for health, wellbeing and society. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of good health, said Chen. “My hope is that people become more mindful about the health benefits of eating for long-term wellbeing.”

—Bethany Augliere

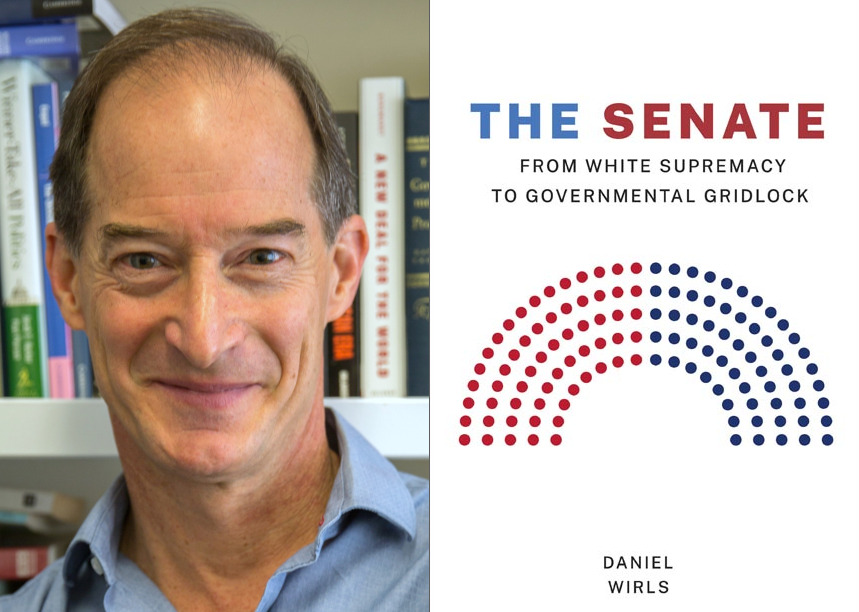

Politics

Senatorial stalemate

Rather than addressing what most Americans recognize as critical issues, including voting rights and climate change, today’s United States Senate serves as a place where legislation—as some have put it—“goes to die.”

How this sad state-of-affairs arose—and what reforms might correct the problem—is the subject of Professor Daniel Wirls’s latest book, The Senate: From White Supremacy to Government Gridlock (University of Virginia Press, 2021). In the book, Wirls discusses, among other matters, how the two Senate features of equal representation and the filibuster, the first fundamental and the second adopted, have effectively stalled lawmaking, maintained white supremacy, and become institutional barriers to democracy. “If we were to start over again, the Senate would have neither,” said Wirls.

The problem arose as urban populations exploded in the 19th and 20th centuries, exacerbating the rural-urban divide. Equal representation meant Senate seats increasingly stacked in favor of less diverse rural areas, resulting in disproportionately reduced sway for the greater numbers of voters living in more diverse urban areas. “We're sending a Senate to Washington that not at all accurately represents the American population,” said Wirls. “Senators elected by a very small minority of the American population can stop anything the majority of voters might want to do.”

—Katie Brown

Molecular, Cell and Developmental Biology

Bon voyage

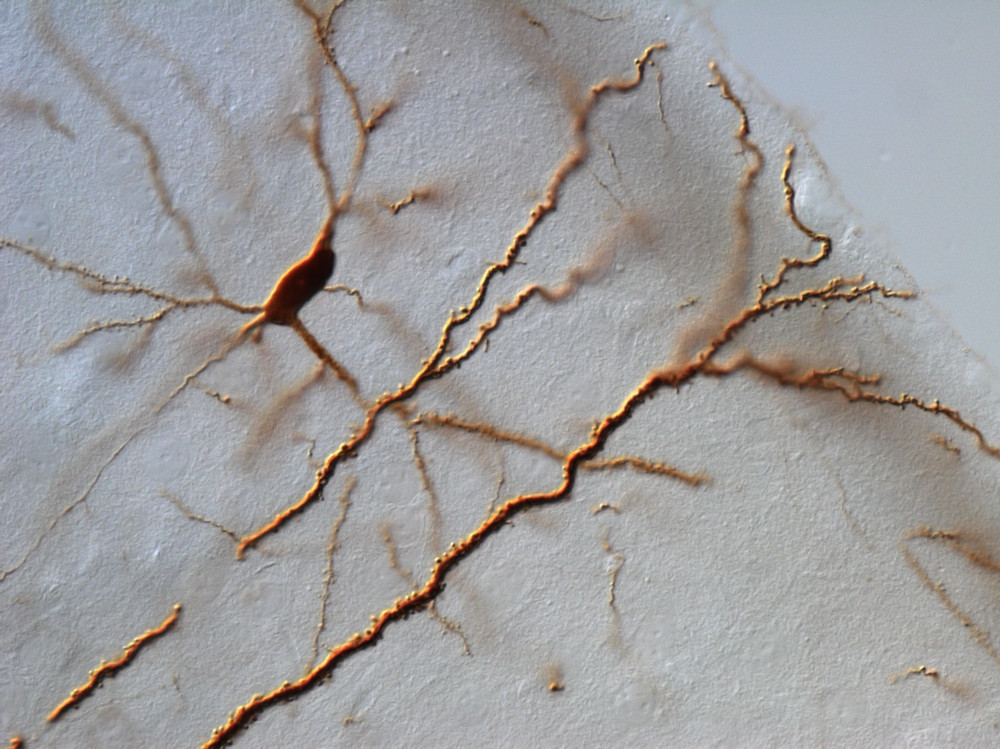

When Professor Yi Zuo gives her research subjects “non-hallucinogenic” psychedelic drugs, she actually does not know they don’t hallucinate. “You can’t ask them,” she said, “because they are mice.” This actually important question aside, her lab’s basic science work supports the growing excitement about the potential clinical use of psychedelic drugs to treat medical conditions like intractable depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Zuo and her team study how connections between neurons—synapses—constantly change, through a process called synaptic plasticity. “Synaptic plasticity means making or losing, strengthening or weakening synapses,” said Zuo. “By changing these connections, you’re basically changing the network of how neurons communicate.”

In their experiments, Zuo’s team explores how external stimuli like stress, disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s), or drugs can physically alter networks of synapses in the brains of their living research animals. They then look for correlates of these brain alterations in the mice’s behavior. In dual papers published in 2021, for example, they reported in one how chronic stress physically rewires neuronal connections, making it harder for the mice to learn. In the second, they reported the reversal of stress-induced brain changes with just one dose of a non-hallucinogenic psychedelic drug. But no hallucinations? The mice aren’t talking.

—Annie Melchor

ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY

Happy places

Though growing scattered across Asia and Africa, spiral gingers (plant family Costaceae) really found their happy place some three million years ago when they took root in Central and South America. It got especially happy for one group of these corkscrew-stemmed plants. Over the millennia, the genus Costus evolved into a whopping 59 neotropical species, sprouting all the way from sea level to the great heights of cloud forests.

A late comer to this plant party, Professor Kathleen Kay began studying Costus two decades ago while earning her doctorate in plant biology from Michigan State University. She zeroed in on neotropical Costus specifically for its unique diversity, perfect for studying how closely related plants become separate, distinct species. “I try to figure out why they stop mating with their close relatives,” said Kay.

More generally, Kay’s research blends field and greenhouse studies with genomics to understand how flowering plants diversify through adaptations and speciation. In a study published in 2020, for example, while Kay and collaborators confirmed a correlation between Costus species richness and mountainous terrain, they also showed how Costus speciation occurred by similar mechanisms regardless of elevation. Beyond its basic science value, her lab’s work could have a more immediate impact. “Understanding how things adapt has important implications for climate change,” said Kay. “Everything’s getting hotter.”

—Katie Brown

History

All that jazz

What do jazz improvisation, African American activist and intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois, and the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) have in common? They are all subjects of books written by historian Eric Porter. Professor Porter describes his research interests as cultural and intellectual history, ethnic studies, music studies, and urban studies—in his own words, “kind of eclectic.”

His latest project, a soon-to-be-published book, A People’s History of SFO (UC Press, 2023), provides a recent history of the Bay Area, where Porter grew up, by focusing on how the airport was developed and how it became a public stage for activism. The book contains more than history, though, touching on “race, class, gender, sexuality, colonialism, and imperialism,” Porter said, all foundational elements of each subject he chooses as his next research muse. “Airports,” he said, “are really interesting places where lots of different people and networks come together.”

With music, jazz enthusiast Porter’s interest centers on how a city’s culture influences the music people make, and vice versa. As “a way of expressing ideas, feelings, and experience,” music reveals a lot about how people relate to each other and their communities. In all his work, Porter said he seeks to understand how urban development shapes people and their communities. “Sometimes it’s representing people who have been marginalized,” he said. “And sometimes it’s complicating familiar narratives and celebrating radical thinking.”

—Emily Harwitz

Literature

Shakespeare asks

Sean Keilen’s lifelong fascination with Shakespeare began early, as an eight-year-old intrigued by a small-town production of Macbeth. Now, as a professor, Keilen channels Shakespeare to examine modern life and connect with both academic and non-academic communities.

Shakespeare remains relevant after 400 years because his work captures human nature, said Keilen, who directs the Shakespeare Workshop, a research center at The Humanities Institute that has hosted public performances, lectures, and discussions since 2013. During the pandemic, in collaboration with long-time partner local theater company Santa Cruz Shakespeare, the workshop organized live virtual productions and conversations in a series called Undiscovered Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s plays hold up a mirror to modern life, providing a powerful vehicle for self-examination, Keilen said. A play that questions monarchy as an institution, for example, can spark conversations about the fragility of our current political system. “No one I work with—students, actors, people in the community—comes to Shakespeare for answers,” said Keilen. “They come for questions we're not asking because we're so focused on our own moment and place and culture.”

“Shakespeare is alien enough to allow us to look at ourselves differently and ask new questions of ourselves,” said Keilen. “But he's connected to us enough that we understand what he's talking about and why it has purchase for us.”

—Erin Malsbury

ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING

Biopower plants

We all know about power generation from the sun and the wind, but it’s probably a surprise to learn that electricity can also come from the dirt beneath our feet. The dirt itself, however, is not the source—it’s the so-called exoelectrogens, mostly bacteria, that inhabit healthy soil all over the world. As they break down and metabolize—i.e., “eat”—complex molecules like sugars, these miniscule organisms release a steady trickle of electrons.

Commensurate with their microbial size, the electron output of a single bacterium is quite small. But their immense numbers and density in the soil can collectively produce enough of a spark for Assistant Professor Colleen Josephson and her collaborators to attempt to harness it. Josephson’s work aims to create what she calls “a mud battery,” more technically known as a microbial fuel cell (MFC). If she succeeds, MFCs will power soil moisture sensor networks on farms, potentially saving a lot of increasingly valuable water.

About 70% of all the potable water we use today goes to agriculture, said Josephson, noting that the sensor networks she envisions could improve the sustainability of farming by saving up to half of this water. And with another expected two billion people added to the world’s population over the next 30 years, “it’s going to be critical,” she said, “to use water more efficiently.”

—Bethany Augliere

Linguistics

Doublespeak

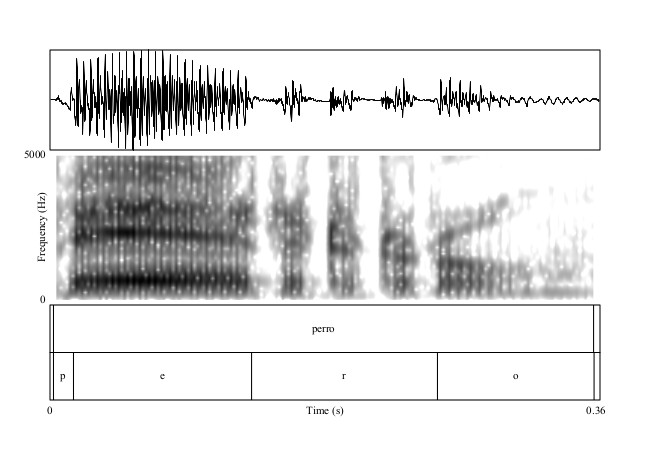

The mental gymnastics of speaking another language requires using a new sound system while suppressing the dominant one of your first language. How people achieve this feat—and its linguistic, social, and cognitive consequences—centers the research of Mark Amengual, associate professor of applied linguistics and director of Spanish Studies. “I’ve always been intrigued by how seamlessly bilinguals switch between languages,” said Amengual, himself multilingual, speaking English, Spanish, and Catalan.

In the UCSC Bilingualism Research Laboratory he directs, Amengual analyzes the acoustic profiles of multi-lingual speech collected under controlled experimental conditions. In one study, for example, Amengual compared two groups of Latino Spanish-English bilinguals—one speaking Spanish at home and not English until starting school and the other exposed to both languages from birth—with a third group of bilinguals who grew up English-speaking and then acquired Spanish by studying it in college. It turns out the degree of exposure to each language in the formative, early years of life has a persistent effect, influencing adult speech acoustics in a quantifiable way.

To get a fuller picture of “what bilingualism is all about,” Amengual also studies speech perception among Indigenous bilingual populations in Mexico who speak Spanish and an endangered language, Hñäñho. “Perception and production,” said Amengual, “are two sides of the same coin.”

—Elizabeth Devitt

EARTH AND PLANETARY SCIENCES

Geological faults

Perusing the library stacks, Tamara Pico, then a Harvard University PhD student, discovered an old book by Nathaniel Shaler in which the eminent 19th-century Harvard geologist argues that certain climates or landscape features produced superior humans in Europe compared to other parts of the world. “No one in my department had any idea,” said Pico.

The discovery prompted Pico, now a UC Santa Cruz assistant professor, to dig into the history of geology to better understand how bias influenced scholarship in the field, whose practitioners were—and largely still are—white and male. The work birthed GeoContext, a collaborative website project that provides historical background to topics covered in undergraduate geology courses. Its teaching modules connect, for example, oceanography with the slave trade, and volcanology with colonialism. Pico hopes teaching this history will help address geology’s diversity issues. “Having a sense of that history helps because bits of that are still here with us,” she said.

In her primary research, Pico models changes in glaciers by measuring how the land that surrounds them moves in response to the weight of the ice. Her interest in geology’s history is a separate endeavor, but she considers it important to think about how it applies to all her work. “I try to put myself in a social context,” she said. “Why is this work valued in my field? Why do I value it? What is the consequence of my doing this?”

—Erin Malsbury

Theater Arts

Inclusive dancing

On September 20, 2018, some 50 Bay Area dance artists, choreographers, educators, funders, and administrators gathered in Oakland for a “long-table discussion.” On the table? A social justice issue still unacknowledged by most in dance—racial inequity. The Oakland public forum, the first of many around the country, kick-started Dancing Around Race, a community engagement project sponsored by Hope Mohr Dance, a dance organization dedicated to “creating and supporting embodied art and social change.”

At the center of the conversations stood their lead organizer, Gerald Casel, a person whose lived experience gives him first-hand knowledge of dance’s racialized issues and the skills and drive to do something about it. Casel wears many hats: queer, Filipino immigrant, first-gen college graduate, highly accomplished dance artist, award-winning performance maker, cultural and community activist. Casel, formerly an associate professor of theater arts, recently left UCSC to become chair of the Dance Department at Rutgers University.

Insights from Dancing Around Race now extend into workshops Casel is piloting, as well as teaching modules for higher education and K–12 performing arts curricula, all directed at facilitating candid discussions in brave spaces. “It’s the system that’s racist, not necessarily the people,” Casel said. “There’s a lot of potentially problematic issues around appropriation, tokenism, and cultural mismatch—we want to unpack all that and talk about it rather than pretend it doesn’t exist.”

—Katie Brown

Environmental Sciences

Sea rescue

Like the birds that still frequent its shores, people once flocked to the Salton Sea. Just hours from Los Angeles, the desiccated lakebed refilled in 1905 with spillover from Colorado River irrigation canals. But since its 1950s heyday as a popular tourist destination, the irrigation runoff that kept the lake filled has diminished, shrinking it dramatically. Wind-laden agrochemical dust off the exposed lakebed contributes to asthma rates in surrounding communities, and rising salinity has killed fish and jeopardizes migrating and nesting birds. Tourist destination no more, the Salton Sea now poses a considerable public health and environmental challenge.

Enter Brent Haddad, director and founder of the Center for Integrated Water Research. Professor Haddad heads a team of faculty, graduate students, outside consultants, and an Independent Review Panel charged with identifying—as part of the state-managed Salton Sea Management Program—a long-term plan for restoring the Salton Sea ecosystem and its languishing surrounding communities. In addition to evaluating proposals for “water importation” to refill the lake, the team’s remit includes considering the area’s economic future. “The region is of immense interest in part because of its potentially massive lithium resources,” Haddad said.

“We don’t have any templates for what we’re doing,” Haddad said. The hope, he said, is that other regions with evaporating lakes around the world can use their Salton Sea restoration process and plans as a model.

—Emily Harwitz