Bon voyage

When Professor Yi Zuo gives her research subjects “non-hallucinogenic” psychedelic drugs, she actually does not know they don’t hallucinate. “You can’t ask them,” she said, “because they are mice.” This actually important question aside, her lab’s basic science work supports the growing excitement about the potential clinical use of psychedelic drugs to treat medical conditions like intractable depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

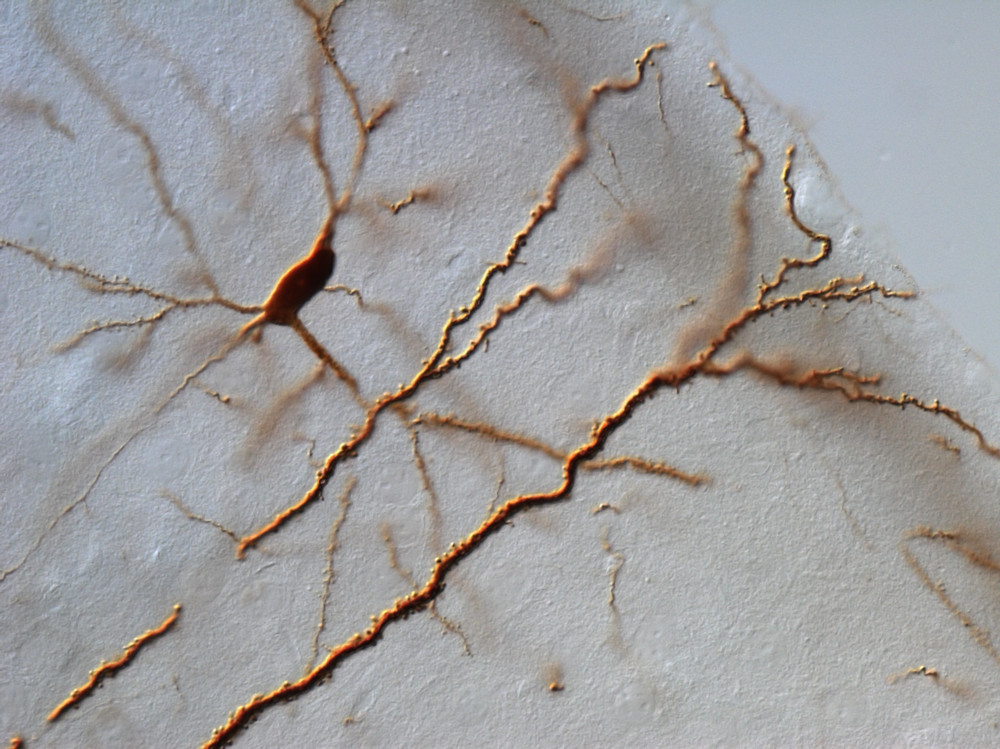

Zuo and her team study how connections between neurons—synapses—constantly change, through a process called synaptic plasticity. “Synaptic plasticity means making or losing, strengthening or weakening synapses,” said Zuo. “By changing these connections, you’re basically changing the network of how neurons communicate.”

In their experiments, Zuo’s team explores how external stimuli like stress, disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s), or drugs can physically alter networks of synapses in the brains of their living research animals. They then look for correlates of these brain alterations in the mice’s behavior. In dual papers published in 2021, for example, they reported in one how chronic stress physically rewires neuronal connections, making it harder for the mice to learn. In the second, they reported the reversal of stress-induced brain changes with just one dose of a non-hallucinogenic psychedelic drug. But no hallucinations? The mice aren’t talking.

—Annie Melchor