Human remains

People's choices shape the ruins they leave behind

Top tourist attractions like Tenochtitlan’s pyramids and the Coliseum’s columns provide fascinating glimpses of faded civilizations, inspiring awe in those who experience them. But how did such crumbled magnificence come to be? According to assistant professor and director of classical studies Martin Devecka, the people in the past who left those ruins shaped what we see today, just as we are shaping our cities now.

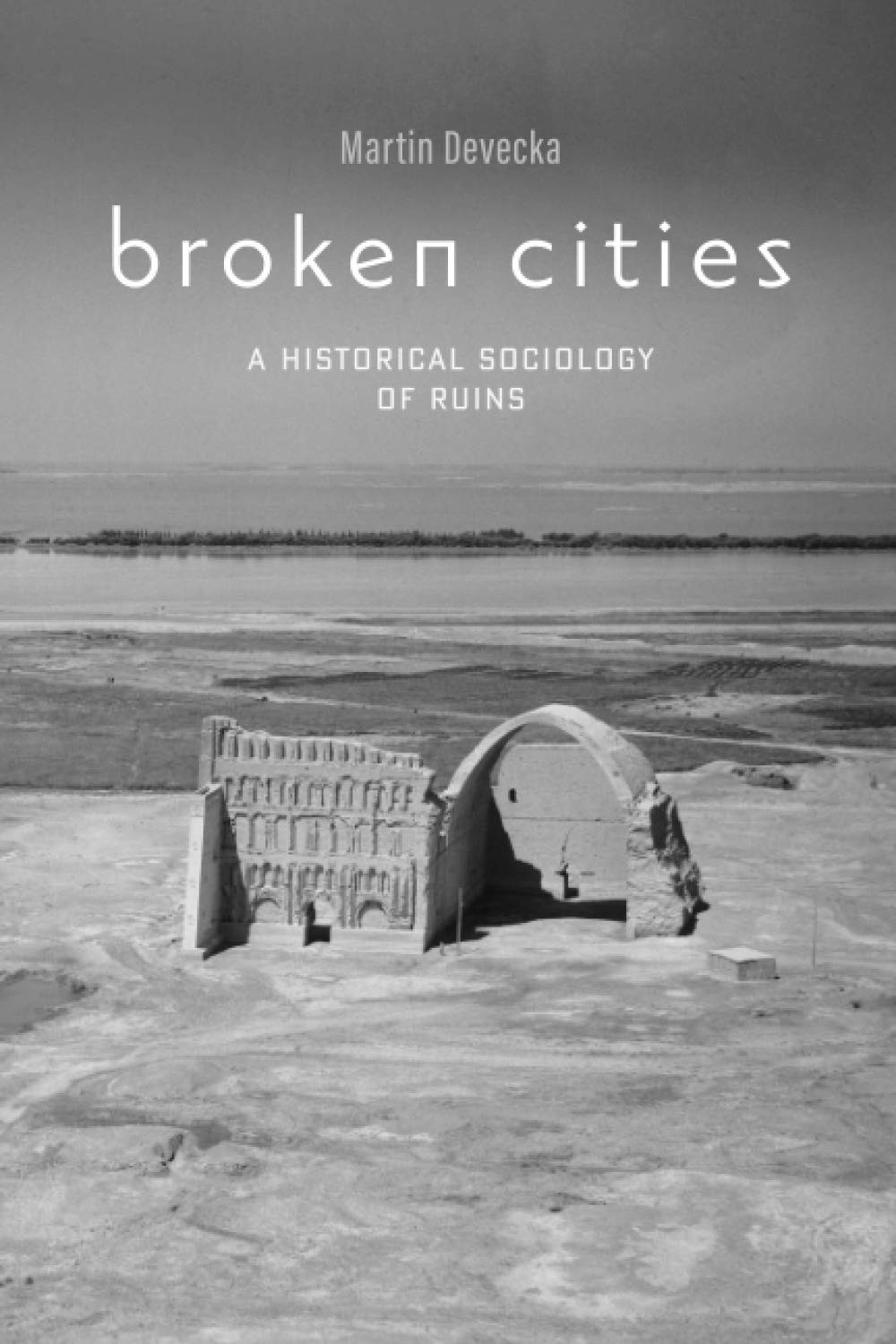

In his book Broken Cities, A Historical Sociology of Ruins (Johns Hopkins Press, 2020), Devecka travels through historical writings from four civilizations of the past to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of ruination as a complex social process. The texts he examined range from legal documents and letters to ancient literature, inscriptions on monuments, and other writings that reveal how people in the past perceived and engaged with their cities. The ruins they left behind reflect deliberate decisions, Devecka argues—they’re not just the result of decay after people moved on.

In case studies of classical Athens, late antique Rome, medieval Baghdad, and 16th-century Mexico City, Devecka shows how human choices—apparent in the texts and other materials people produced describing life at the time—shaped what remains of these cities of the past. Political forces, religious beliefs, and cultural symbolism all contributed to decisions to repopulate or abandon a city after a conquest, or repurpose toppled pillars to build a new temple after an earthquake. Yes, military conflict or natural disasters often forced people to choose, but their choices determined what became a ruin, and how.

Ruins have long been viewed through the lens of European romantic tradition, said Brown University associate professor of archaeology Felipe Rojas Silva, an architect by training whose own research focuses on the material remains of ruined cities. Typically, researchers compare and contrast how people from different cultures recorded ruins and engaged with them. “Martin’s work is unusual and bold and exciting,” Rojas said, “because he’s shown connections and continuity within civilizations over time.”

We spoke with Devecka about how ruins represent more than mere decay, and how his study of ancient cities suggests we should think about the ruins we’re creating in our own time.

What do ancient writings reveal that’s not obvious in the ruins themselves? There's a question that archaeologists always ask about a ruin site: what was this used for? I think more about why people stopped using it. It's not a question that you can answer by looking at the site itself. You can say, for example, whether it was burned. But when you look deeper at the site, you see other burn layers where the city had been sacked before, and people just rebuilt it. Why did this particular disaster, this particular sacking of the city cause it to be abandoned afterward? Catastrophe is just the pretext for ruination, not the cause.

How did people in the past think about ruins and their formation? Ways of thinking about ruins are idiosyncratic. In other words, ruins belong to particular times and places—there's not some kind of narrative that starts in one place and ends where we are now.

For example, ruin-making in Greece is really a process of equilibrium. Soon after areas of the city were depopulated, people went back, so in the classical period there are not really any ruins. But in Rome, there's this strong cultural pressure against returning to the city’s mythical source in Troy, the city from which Aeneas immigrated. If they re-found it, they might invoke this weird curse from Juno and be conquered by the Greeks again. That’s coupled with an interest in making sure the empire has this trajectory toward growth, where all roads do lead to Rome. In medieval Islamic cities such as Baghdad, cities are ruined but not depopulated. Just neighborhoods become depopulated and people kind of learn to live with ruins next door. In Mexico, people deliberately made ruins during warfare. Creating ruins signified conquests, so much so that the glyph for a conquered city is a picture of its main temple burning. Modern Mexico City sits on the ruins of Tenochtitlan, in a way confirming the ruin of the old city.

With so many differences, are there also similarities? Yes, ruins reveal who’s in power. Is the urban population allowed to control itself, or is it under somebody else's control? Thinking back to the Ostrogoth king Theodoric, there’s a letter in which he tells all these people who've left their cities for fortified hilltops that they need to go back. He is the king of Italy at this point, so you would think he would be in a position of power. But it’s clear in that letter that mid-level Roman aristocrats, people who belong to the senatorial class, actually have more control over where the population goes.

What are the challenges of studying ruin-making via historical writings? It’s challenging to come up with a language to talk about these sites that doesn't necessarily prejudice the results. Not only do all of these different languages have different words for ruins, but the words are often quite different in source and origin. In late antique materials, the Latin word is ruina, which refers to something which has collapsed. It stems from a verb that means to rush downward, or to collapse. Whereas in Greek, the word is erepia, which has to do with tearing something down. It's an active process that points us toward the agent of ruination. Another Greek word used is edaphé, which means basement or foundation, so the ruin is almost perceived as part of a building’s architecture.

Why do these nuances matter? Realizing that other people used to think about these sites really differently is a good way of distancing ourselves from our own reflexively held views.

What is the reflexive, modern perspective on ancient ruins? We tend to think about them as things located in the past, something impossibly distant from us. This very past-focused attitude towards ruins is something that develops in the century where my book ends. It's especially coming into full bloom in the period of Romanticism, where you see this very stereotypical, modern attitude of ruin-gazing. We appreciate it purely aesthetically. It doesn't really matter to us, except in so far as we can look at it.

What are some ruins forming today, and how should we think about them? Fukushima in Japan has certainly emerged as a ruin during our lifetimes. There was one big disaster, but then why didn't people just move back? There’s an obvious answer, which is that it's not safe. But how do people know that? Compare that to the U.S., where people live in sites left unsafe as a result of the Cold War, ecological disasters, or pollution. Nobody has told them to leave. In Chernobyl, the Soviet government telling people they have to leave and can’t come back was key to creating that ruin. The Japanese government has done it in a different way, because the relationship of Japanese culture to nuclear disasters is a lot more complicated. In both cases, the disaster presents an opportunity for something to happen. But what makes the ruin form is a quite specific set of cultures and attitudes.

Another example is Detroit, where in real time, wealthy and powerful elites have essentially depopulated the city by driving a move to the suburbs. You can see this in the way it’s written and talked about in the media—the city is ruined so people are moving to the suburbs. We’re no longer going to invest a lot of money in keeping this ruined city going. And then you have the really interesting case of ruin profiteers, who buy up ruined architecture and preserve it for photo shoots and the like. We should be aware that we are making the past too. We are creating a past for others to see all the time.