Displacement

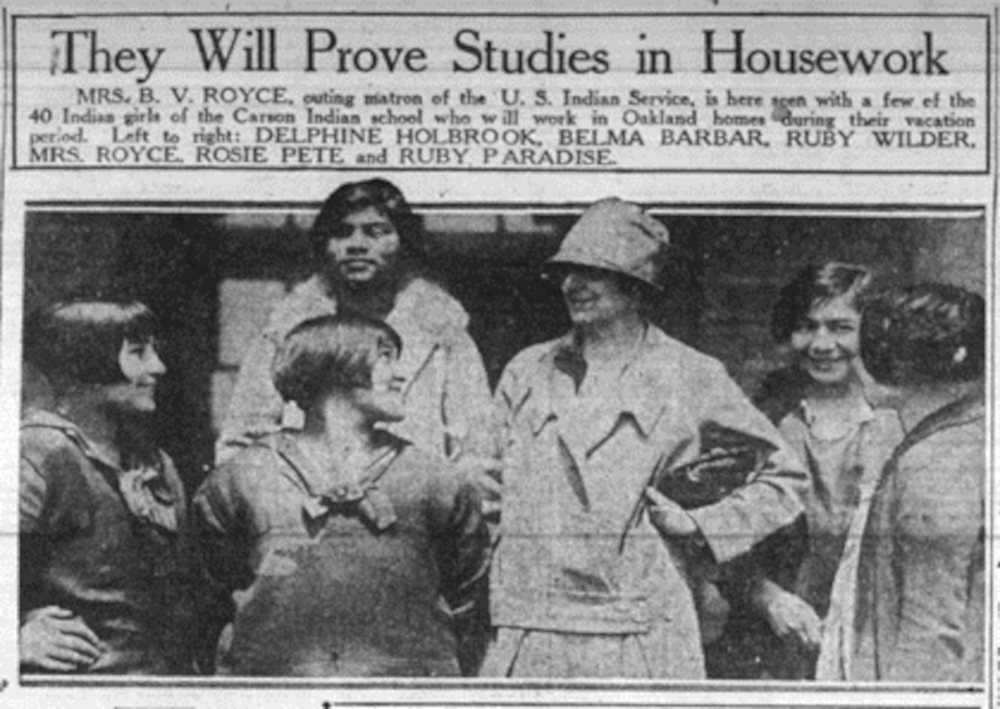

Between 1918 and 1942, as part of efforts to assimilate Native peoples, thousands of women worked for white, affluent families in the Bay Area as domestic help during holidays away from their Indian boarding schools. In hindsight, this “outing program” and similar ones throughout the country actually embodied a federal campaign of labor exploitation, according to Assistant Professor Caitlin Keliiaa.

In a government archive housed in San Bruno, Keliiaa unearthed roughly 4,000 letters, photos, and bank statements that trace the lives of the Native women placed in the Bay Area Outing Program. Her study of these documents reveals strict monitoring by the white outing matrons who oversaw them. Women suspected of sexual activity, for example, were “surveilled, managed, sent to detention homes, and sometimes arrested,” Keliiaa said. In rare instances, women ran away or even died while on placement.

The legacy of such outing programs, documented in Keliiaa’s book-in-progress, Unsettling Domesticity: Native Women and 20th-Century Federal Indian Policy in the San Francisco Bay Area, is not entirely negative. Program participants who stayed or returned formed a resilient Native community decades before more extensive migration to the Bay Area from reservations. Social clubs for Native people established by the outing program—to meet under supervision—also persisted, creating what Keliiaa calls “foundational spaces” for displaced Natives to build community and celebrate their tribal cultures.

*— *