Disparate impacts

As the pandemic surged, so did inequality

One way or another, everyone has felt the pain of COVID-19. As the virus left its mark, people reeled—and continue to suffer—from the sudden and drastic changes caused by isolate-in-place policies, jobs lost or made more difficult, sickness, and the loss of loved ones. But some have felt the pain much more than others. People of color and low-income families have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, shining a spotlight on social, health, and economic inequities deeply rooted in the U.S.

Inequality has long been the focus of two UC Santa Cruz researchers, professor of developmental psychology Margarita Azmitia and professor of economics Robert Fairlie. Though they study different aspects of the issue, child and adolescent development for Azmitia and business and labor for Fairlie, both have kept a close eye on the pandemic’s path, tracking how it has selectively struck the disadvantaged among us. By sharing their data and insights and giving disadvantaged people a voice, they’re helping to ensure this suddenly escalated problem remains front and center for the policymakers tasked with solving it.

Paying attention

Azmitia has spent her career studying how peers, family, and schools affect the development of children and adolescents. In early 2020, she joined the rapid response network of the advocacy organization Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC). Initially assembled to brief legislators on the impacts of deportation and immigration detention policies, the network quickly shifted gears to explore how the pandemic was affecting vulnerable children and adolescents.

Azmitia’s role included digging into the academic literature, providing feedback on drafts, and helping to write parts of the team’s May 2020 policy brief. In addition to educating lawmakers about the scope of the problem, Mitigating the Implications of Coronavirus Pandemic on Families provided research-informed policy recommendations on how to best support students’ needs. Over the past year, many families, particularly those in low-income and rural areas, struggled to keep up with remote schooling during the pandemic, thus exacerbating prior resource gaps. “This was an opportunity to say there are a lot of people that we’re missing, and we need to do something,” said Azmitia.

The brief highlighted how more than 21 million people in the U.S. have unreliable access to internet and digital devices, making online classes difficult or impossible to attend for many children and youth. And if they do have access, families may just have one laptop. In many cases, it’s the parent working from home “who needs to bring in the paycheck that must use the device, potentially interfering with the kids’ online classes,” said Taryn Morrissey, professor of public administration and policy at American University. “It’s a terrible decision that families have to make.” According to Morrissey, whose work centers on improving public policy for vulnerable children, Azmitia’s research on how resource gaps impact kids’ overall development is crucial for informing future legislation aimed at addressing this disadvantage.

In the RPC policy brief, Azmitia and her collaborators cited research showing that—even before the pandemic—youth without access to technological devices and the internet already performed worse in school than those with such access. Kids living in poverty were also more likely to live in crowded homes with little-to-no space for them to engage in their now online classes. Additionally, decreased access to child care meant older kids were often expected to take care of their younger siblings, further impeding their ability to engage in virtual learning. “The pandemic made the resource gap incredibly apparent,” said Azmitia. “It has done away with all of these resources, leaving kids basically on their own.”

The situation will likely have lasting consequences, Azmitia said. As detailed in the policy brief, losing that connection to school means low-income and rural students are at higher risk for dropping out, suffering mental health issues, and being less employable than their peers. “I think we’re going to see an increase in high school dropouts,” said Azmitia. “I also worry about the increase in mental health issues. There are lots of kids reporting anxiety, depression, and disordered eating, and we don’t have the support systems for that.” Kids are resilient, she said, but that may not be enough to keep the more vulnerable ones from suffering longer-term difficulties in the absence of school and community programs and other support.

Lights off

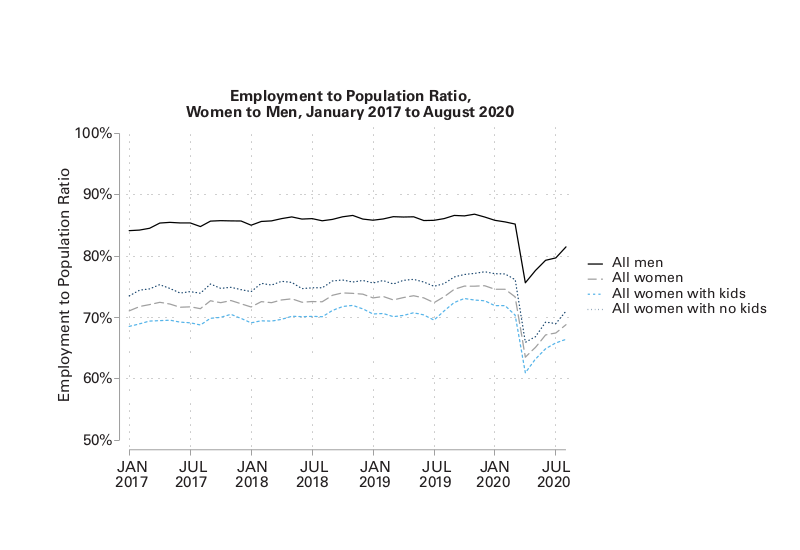

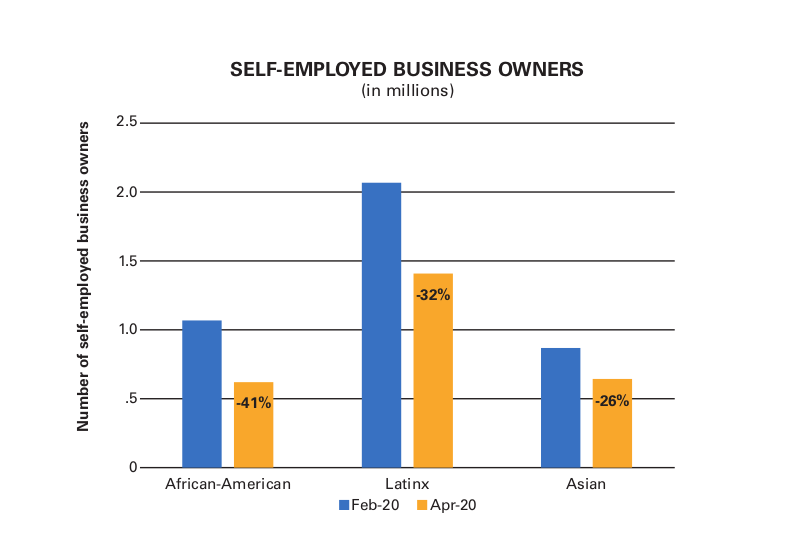

The pandemic has Fairlie worried as well. Rather than kids, however, Fairlie, whose study of racial inequities in business spans 25 years, sees the increased suffering of adults in the workforce. Based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau, his early pandemic research revealed drops last February to April in the number of Black-, Latinx-, and Asian-owned businesses of 41, 32, and 26 percent, respectively. In addition, female business owners were disproportionally hit, with 25 percent of them shutting down. Fairlie saw firsthand the early impact of the pandemic on businesses on Mission Street in San Francisco. “Lights were off. Chairs were on top of tables. We were starting to see then that this was going to be long lasting,” he said.

In another study published in January 2021, Fairlie and a colleague found evidence that the first round of the $659 billion Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP, to help struggling businesses did not go towards minority communities. Instead, the money was doled out to established banks, which were then expected to loan the money to businesses in need. The problem is that minority-owned businesses don’t often work with big banks. “They tend to work with smaller community lenders instead,” Fairlie said. After a public outcry, the second round of PPP loans seemed to be more evenly distributed, according to Fairlie. Currently, he is watching as the third round of PPP data slowly rolls out to see if this trend continues.

“This work highlights how the COVID pandemic and its related recession has disproportionally impacted people of color,” said Connie Evans, president and CEO of the Association for Enterprise Opportunity (AEO), an organization that helps underserved entrepreneurs grow their businesses. Fairlie contributed original analyses to AEO for their 2017 report The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America, which “paints a picture of the diversity of Black businesses and discusses three major challenges impeding Black business development: a massive wealth gap, a credit gap, and a trust gap fueled through bias.” An understanding of each of these challenges is needed, said Evans, to build effective solutions that fit the unique needs of Black-owned businesses. “That’s how you drive towards inclusive business ownership and an inclusive economy.”

Moving forward, Fairlie intends to dig deeper into the government data to further investigate the racial disparities laid bare by the pandemic. “There are variations in PPP loans given to businesses across states, cities, towns,” he said. “And we have to look at those people who did get early investments before shutting things down. Were they able to reopen faster? It’s a huge question.”

Pushing progress

Both Azmitia and Fairlie aim to influence policy by getting the word out about their research. The RCP brief contributed to calls for a range of policy shifts, including more technological support for students who are learning remotely, extending internet “hotspots” for increased access, supporting students with learning disabilities and differences, and plans to address the learning gap that many students have inevitably experienced once the pandemic eases up. Fairlie’s work has been cited in a bill to expand the Minority Business Development Agency, a federal agency tasked with promoting growth of minority-owned businesses, and he was asked to testify in front of the U.S. House of Representatives and California State Assembly. He has also provided data on businesses and COVID-19 for some of Vice President Kamala Harris’s speeches and helped the U.S. Senate in its analysis of PPP loans.

The March 2021 federal passage of the $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package appears to offer promise. The American Rescue Plan directs more than $120 billion towards K-12 schools, expands subsidies to help Americans afford health insurance, gives families up to $3,600 per child as a tax credit, and makes millions more people eligible for unemployment insurance. This is a major step up from previous pandemic responses by the federal government, including the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which, according to Azmitia, had major flaws and did not sufficiently address the needs of children and students.

Azmitia said she is encouraged on a local level by how teachers in Santa Cruz have stepped up: “They’ve mastered the idea that we can’t have kids learning on screens for long periods, so they’re using other methods.” It’s the same at the university level, where professors are rethinking learning and testing, she said; we all expect life to go back to a new normal eventually, but hopefully more people now see that minority groups who have been left out of the conversation for so long deserve a voice. “We need to appreciate their backgrounds, their struggles, and what they can add. This pandemic has cost everybody.”