Coral as capital

Showing how coastal conservation pays off

In October 2020, Hurricane Delta smacked the Yucatan coast just south of Cancun. While it largely spared homes and businesses, it “ransacked” the coral reef just offshore, as newspapers reported. For declining coral ecosystems, already weakened around the world by climate change, such storms can be the breaking point.

But this time, the reef carried some unprecedented protection: an insurance policy. The claim paid out $850,000 to help stabilize the reef and reattach fragments of surviving coral.

Key to making this scheme a reality was the work of research professor Michael Beck and his team at the UC Santa Cruz Institute of Marine Sciences’ Coastal Resilience Lab. Their extensive research has shown how coastal ecosystems—reefs, mangroves, and salt marshes—constitute tangible financial assets, “natural defenses” that dampen storm waves to prevent flooding. They argue that such “natural capital” is a sound investment because it often shields the coast from damage more cost effectively than any artificial barrier.

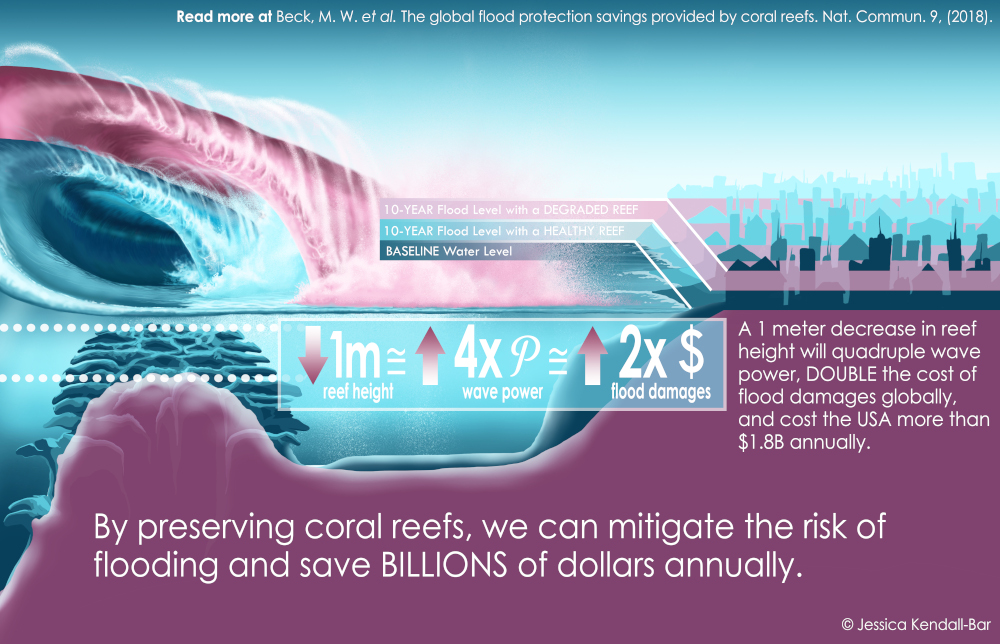

The heart of the team’s work is putting dollar values on the flood protection provided by natural habitats. This accounting underlies the first rigorous estimates of the global flood protection value of coral reefs and mangroves: $4 billion and $65 billion every year, respectively. At a more local scale, their work is helping to steer disaster preparedness and recovery funding toward conservation. “Most of the money currently goes to artificial solutions, which further degrade ecosystems,” Beck said, “We need to do some jujitsu on disaster spending, or we’re going to lose more habitats.”

Building consensus

For decades, ecologists have studied and quantified how people benefit from coastal conservation through, for example, fishing, tourism, and flood protection. But they typically use ecological models that are unfamiliar or novel to engineers and insurers, Beck said. “The most important thing we’ve done,” he said, “is to go to stakeholders and decision-makers and say, ‘Let’s see if we can figure out how to include nature in your engineering and risk assessment models.”

Figuring that out in a way that suits everyone is a difficult task. Insurers need to be convinced that they can treat habitat like built structures in their models. And conservationists need to believe that they can protect biodiversity at the same time as people and property. In the Cancun example, The Nature Conservancy, insurance company Swiss Re, and the state government of Quintana Roo, Mexico, all ultimately agreed on a framework that tied ecosystems and infrastructure together with enough rigor and detail to develop an insurance policy that covers storm damages to the reef. Beck’s team was a key partner in the development from the beginning. “Getting these different disciplines to talk to each other and build an integrated model, so that you could actually decide, is a very rare talent,” said Glenn-Marie Lange, an economist and chief technical adviser for the World Bank’s Natural Capital Accounting program.

Elsewhere in the world, Beck has led research aimed at supporting other local conservation efforts. One such study showed that restoration of salt marshes and oyster reefs on the U.S. Gulf Coast could produce $7 in flood protection benefits for every dollar spent in habitat restoration. In the Caribbean nation of Grenada, Beck worked with associate research professor Borja Reguero to help design a coral restoration project for flood protection and to slow further damage to the coastline from erosion.

Climbing onboard

According to his many collaborators, Beck’s success stems from his ability to straddle multiple disciplines—and his collegiality. “He’s really good at understanding things outside his expertise,” said Curt Storlazzi (Ph.D. ‘00), a frequent Beck collaborator and research geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey. “There's a lot of great scientists, but there’s very few great scientists you actually want to work with.”

Along with insurance companies, other deep-pocketed institutions have climbed onboard Beck’s conservation train. The World Bank has used his team’s work to support its funding of mangrove restoration in the Philippines. The Federal Emergency Management Agency is making it easier to fund habitat restoration for flood protection instead of just dikes and seawalls. In late 2020, the Department of Defense announced a funding initiative—“Reefense”—to spur research on “self-healing, hybrid biological and engineered reef-mimicking structures” to protect military installations and personnel. And capping the year 2020, the global insurance company AXA funded a €1 million ($1.19 million), five-year grant to UCSC, naming Beck to the AXA Chair in Coastal Resilience.

One limitation of the work, Beck said, may be its emphasis to date on conservation near high-value property. Something like the Cancun reef insurance arrangement is “not even an option” in less-developed southern Belize, said Lisa Carne (B.A. ‘93), founder and executive director of Fragments of Hope, a Belizean nonprofit focused on reef restoration.

To address this concern, Beck is broadening his approach. One research proposal, for example, would engage community stakeholders in Florida, the Virgin Islands, and Belize in finding ways to reduce the vulnerability of low-income people to storms. Still, finance needs to stay in the picture, said Maya Trotz, a collaborator on the proposal and associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of South Florida. “Until we get out of a system where so much focus is placed on economic value,” Trotz said, “I do think we have to play the game.”