BRIEF inquiries

Computational media

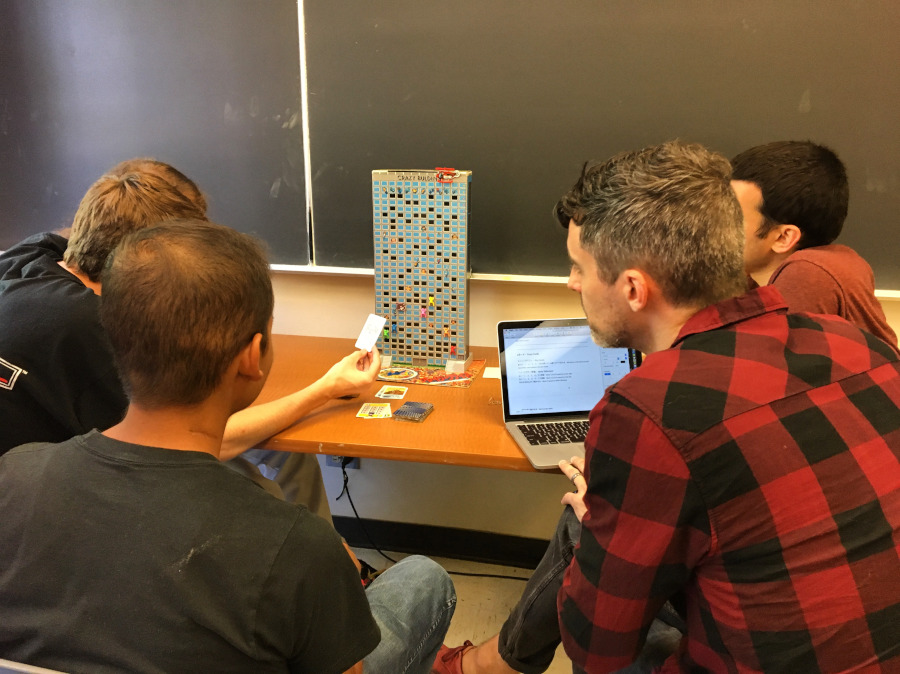

Board game joy

When teaching professor Nathan Altice first started looking for board game adaptations of video games in 2017, he stumbled down a rabbit hole of possibilities from game-loving Japan. “And then,” he said, “I made the mistake of saying, ‘Maybe I’ll buy one.’” Today, Altice’s UCSC office harbors more than 400 Japanese board games, both adaptations and originals, the earliest dating back to 1905. Many can be explored via digital scans and translations on his Analog Joy Club website.

Board games might seem like a trivial pastime, but “games really reflect and embody the culture and values of the societies they come from,” Altice said. For example, Jinsei, the Japanese version of the Milton-Bradley board game Life, introduced as Japan was deep into the economic and social transformation that started after World War II, gained immense popularity from both its aspirational connection to an American lifestyle and its similarity to a centuries-old type of Japanese board games. In some early versions of these sugoroku, Altice said, players roll dice to follow a pathway resembling a Buddhist scroll, ascending vertically—a metaphor for spiritual enlightenment.

Archiving the games protects these fragile, ephemeral historical records that “connect to the way we express ourselves as human beings,” Altice said. “To me, this is an important cultural preservation project.”

*— *

Chemistry and Biochemistry

Watching the clock

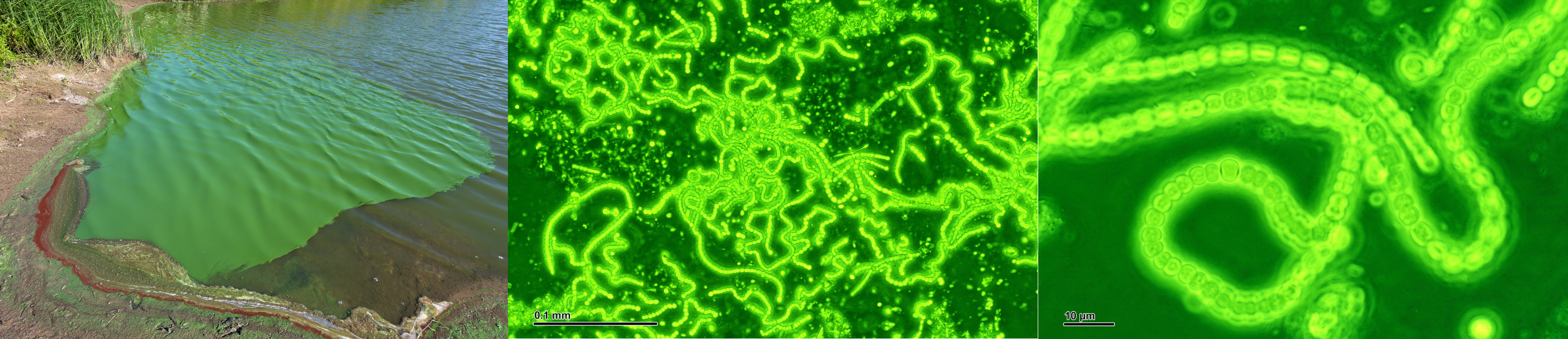

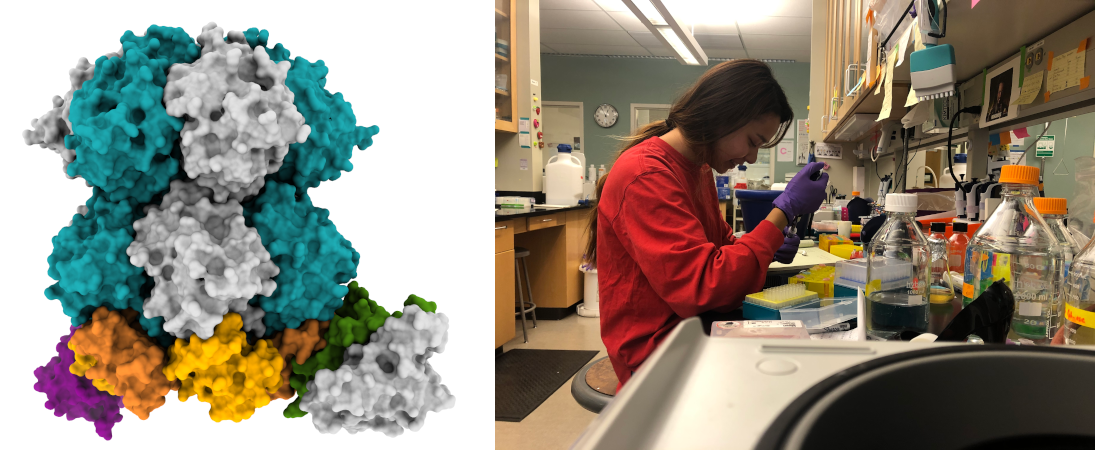

A ubiquitous blue-green bacteria found in ponds and lakes worldwide may provide the key to unlocking how life on Earth keeps track of day and night. These cyanobacteria—single-celled, microscopic organisms that create energy from sunlight—provide a simple system that Professor Carrie Partch and her collaborators have harnessed to better probe the intricate workings of biological clocks, the molecular machines that keep time in all living organisms.

The cyanobacterial clock, one of the most ancient on Earth, ticks in rhythm with each day, crucially triggering the generation of energy from sunlight during the day and then tripping the switch to use that energy in the dark. The goal of the Partch lab’s cyanobacteria research is to reveal, on a molecular level, how this rudimentary clock encodes its timing, how it aligns itself with its environment, and how it communicates time to other parts of the cell.

In a recent report in the prestigious journal Science, the researchers detail their success in recreating the cyanobacterial clock protein-by-protein in a test tube. By letting them perform straightforward experiments not previously possible, the model system is allowing them to uncover new steps in the molecular transformations that keep the clock ticking. “The cyanobacterial clock,” Partch said, “is helping us understand the general principles that make a biological clock.”

*— *

Astronomy and Astrophysics

Dwarves and dark matter

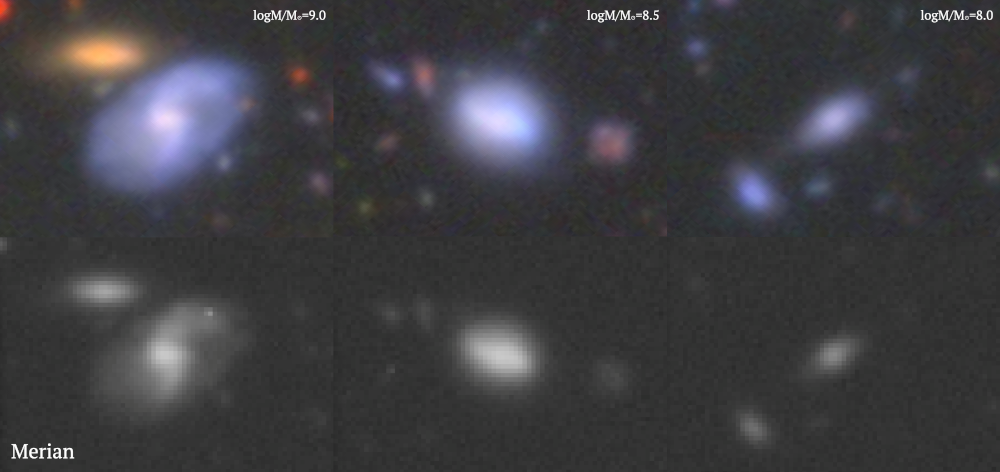

Starting small can sometimes help tackle a big question, like the nature of dark matter. That’s the hope of Assistant Professor Alexie Leauthaud, whose research features dwarf galaxies, the most common—but also most elusive—galaxies in the Universe. Cosmologists refer to these relatively tiny collections of stars (e.g., one billion versus our Milky Way’s 200–400 billion) as “laboratories for dark matter,” Leauthaud said, because they contain copious amounts of the mysterious substance.

With Princeton’s Jenny Greene, Leauthaud co-leads the Merian Survey, an international research collaboration that in March 2021 began using the Blanco Telescope in Chile to map and assess 100,000 dwarf galaxies. Captured through custom-made filters, the discovery of so many dwarf galaxies will enable the astronomers to use a technique called gravitational lensing to measure—for the first time—the amount of dark matter they contain. While light normally travels in a straight line, gravitational forces warp its path. Measuring this warp with gravitational lensing infers the mass of a galaxy: the bigger the deviation, the bigger the mass and how much dark matter is present, Leauthaud said.

Given the massive amount of data the survey will collect, Leauthaud anticipates “exciting science,” including about the extent, distribution, and nature of dark matter and how it varies between galaxies. “We’re pushing into new territory,” she said.

*— *

Applied Mathematics

Bandages with brains

Assistant Professor Marcella Gomez is teaching artificial intelligence learning models to heal. With electrical and computer engineering professors Marco Rolandi and Mircea Teodorescu, Gomez co-leads a collaborative project that includes clinical researchers at UC Davis and Tufts University. Funded by a $16 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the project aims to develop a “smart bandage” that can speed the healing of difficult wounds, like those suffered by soldiers with battlefield injuries from explosions. “Our task is to identify where in the healing process we can intervene to accelerate wound closure,” Gomez said.

To monitor the wound, the smart bandage will contain optical sensors currently being developed by Teodorescu’s team. It will also incorporate a Rolandi team–developed bioelectronic device to deliver ions and biochemicals. What molecules and when to administer them will depend on the bandage’s “brain”—the artificial intelligence system being developed by Gomez.

“We’ll monitor the wounds in real-time, and my algorithms will process and interpret the images to say, for example, ‘Oh, we’ve started inflammation!’” Gomez said, prompting the bandage to release specific biochemicals. Eventually, she said, the technology could be adapted to help heal chronic sores, like those caused by diabetes, which burden a substantial number of patients and cost the health care system billions annually.

*— *

Film and Digital Media

Capturing complexity

When Associate Professor Jennifer Maytorena Taylor began shooting a new project in early 2016, she didn’t realize how much her study of the small town of Rutland, Vermont—where she lived for a time when young—would mirror America’s social and political turmoil. Centered around a mayor’s decision to settle Syrian refugees in the town and how its 15,000 citizens responded, the resulting film, For the Love of Rutland, explores the persistent problems of poverty and addiction and the increasingly divisive issues of cultural identity and nationalism.

Her goal for the documentary, Taylor said, was to avoid portraying Rutland as simply a rural town in decline, to show it as “the complex entity it is, capturing as much nuance and contradiction as possible.” The film follows Stacie Griffin, a lifelong Rutland resident whose life has been marked by poverty and substance abuse. Initially wary of the refugees resettling in her low-income neighborhood, Griffin ultimately finds purpose in civic engagement, advocating for change and community building that includes Rutland’s newest inhabitants.

Taylor teaches her students the same ethical practices and principles that have guided her more than two decades of work as an award-winning filmmaker of feature and short documentary films. “Our job is to be honest,” she said. “I come in with a ‘do no harm’ commitment and an assumption that everybody deserves dignity.”

*— *

History

Back to the future

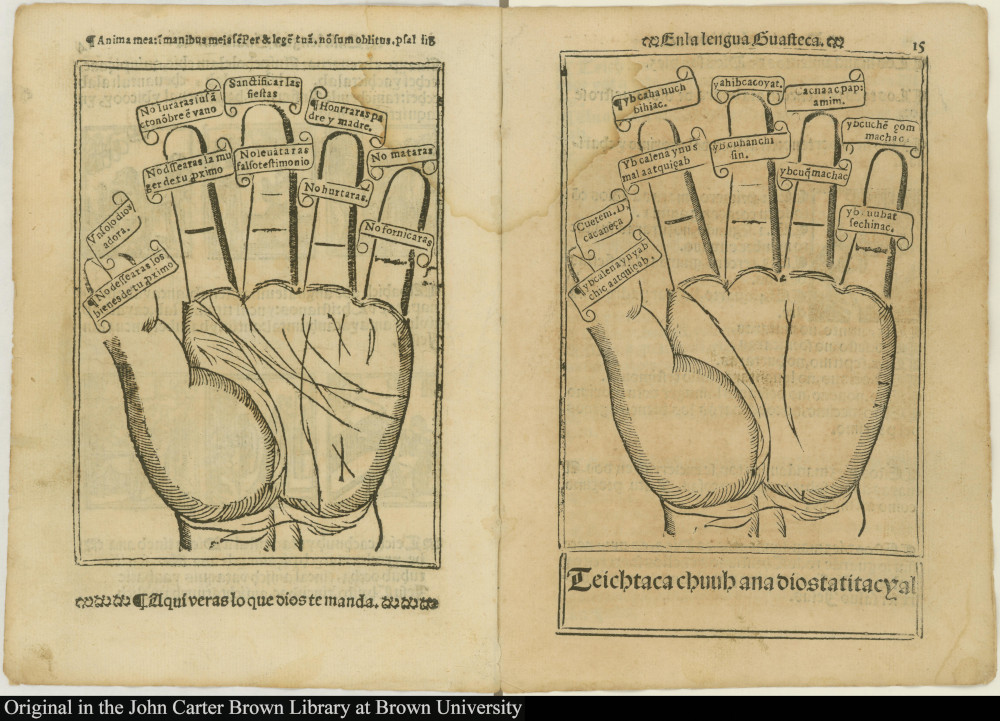

Historians typically write about how the past has shaped the present. Professor Matt O’Hara contends it’s valuable to also consider how the past shaped the future. In his latest book, The History of the Future in Colonial Mexico (Yale University Press, 2018), O’Hara explores the world of colonial Mexico by asking questions about how people’s perceptions of the future prompted their actions.

“Sometimes we forget that the people we study, most of the time, were thinking about tomorrow or three weeks from then, or slightly more long-term,” O’Hara said. “How am I going to get through the year, or leave something to my kids?” O’Hara’s analysis of a broad range of archival materials, from legal documents to Inquisition records, shows how people living in 18th- and 19th-century Mexico—regardless of their education or social status—understood complex legal and theological issues. In addition to governing people’s daily activities with regards to finances, health, and the natural world, these dogmas also fashioned the future.

It’s become clear to O’Hara that critical thinking about what’s to come is essential to better understand both the past and present. “This last year proved the importance of thinking about the future,” he said, “because we all saw our futures change radically.”

*— *

Writing program

Assessing access

At the 2019 annual meeting of the Rhetoric Society of America, teaching professor and disability scholar-activist Amy Vidali led a working group that mapped the accessibility of the meeting site, the campus of the University of Nevada, Reno. “We didn’t want it to be just about ramps,” said Vidali. Drawing from the field of rhetorical cartography (the use of maps as tools for persuasion), the group attempted to geographically locate the unmet access needs of people with physical disabilities, as well as those with conditions like depression and autism, which are less commonly considered in determining accessibility.

Upon returning to Santa Cruz, Vidali decided to try a similar mapping of her home campus. When one of her students, sophomore Katie Felberg (class of ‘22), expressed interest, the two started the project as an independent study. Felberg’s cataloging of the campus’s steep slopes revealed the inaccessibility of large areas from the student bus, including the location of the Disability Resource Center. She also found much of the indoor space lit by fluorescent bulbs, making it difficult to use by some people with migraines or other disabilities.

Vidali hopes to continue the project—halted by the pandemic—when students return to campus. In addition to providing a practical resource for people with disabilities, the map will also serve, she said, “as an activist statement about how inaccessible the campus is.”

*— *

Education

Remote teaching

In March 2020, the pandemic forced associate professor Lora Bartlett to shift her Introduction to Educational Issues class of 300 students to online lessons. Despite having taught the course for years, she found the pivot jarring: “I suddenly felt like a novice.”

Knowing that educators nationwide were likely having similar experiences, Bartlett and fellow principal investigators at UC Berkeley and Lewis & Clark College launched the Suddenly Distant Research Project. To better understand how state and local pandemic restrictions challenged teachers and reshaped education, the initiative’s collaborators conducted intensive interviews with 75 K–12 educators in nine states, chosen based on their COVID-19 death rates and strength of their teacher unions.

The group’s first interim report (November 2020) documented teachers’ initial reactions to the emergency situation in the spring; the second (January 2021), their experiences in the fall as pandemic restrictions continued. One notable finding was how public treatment of teachers changed over that time. “In the spring, teachers felt celebrated as heroes,” Bartlett said. “In the fall, they felt vilified as obstacles to schools reopening.”

The results also showed a groundswell in organizing by teachers. In response to this push to consider their voices, which Bartlett said will “no doubt” continue, states with strong teachers’ unions, like California, have already negotiated protections to support educators.

*— *

Environmental studies

Healing the Earth

On June 5, 2021, World Environment Day, the United Nations officially launched its Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, “a rallying call for the protection and revival of ecosystems all around the world, for the benefit of people and nature.” The ambitious program aims to prompt and bolster global efforts to halt degradation and restore ecosystems to health, thereby enhancing people’s livelihoods, counteracting climate change, and halting the collapse of biodiversity.

In a fortunate convergence of timing, it so happens that Professor Karen Holl has written what could serve as the playbook for this grand effort, her Primer of Ecological Restoration (Island Press, 2020). Holl said she created the primer for anyone interested in ecosystem restoration, whether students, practitioners, or backyard conservationists—“I was committed to keeping it succinct, and as low-priced as possible.”

The primer covers the broad science of restoration, and also the roles played by economic stakeholders, policy makers, and local communities. Each of these participants has unique but also intertwined needs, and Holl hopes her book provides the guidance needed to avoid failed projects. Ideally, ecosystems should be protected; when needed, though, restoration plans should crucially include forward thinking. “We used to use the past as the template for restoration,” Holl said. However, she said, given climate change, restored landscapes will likely need to change too.

*— *

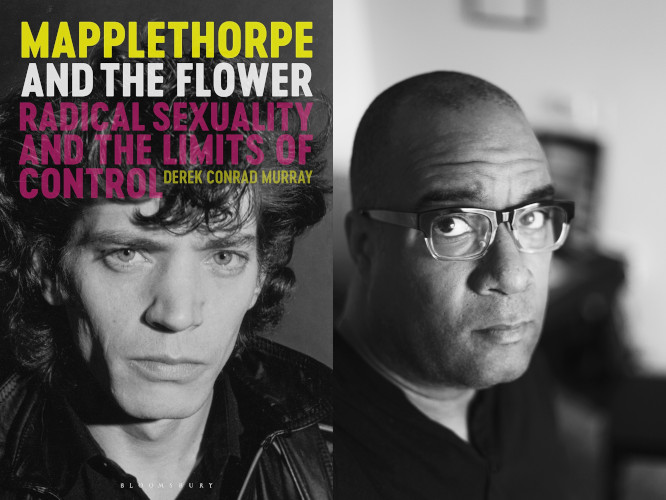

History of art nd visual culture

Deflowering

Flowers as symbols are loaded with meaning. So, what does a flower mean when seen through the lens of Robert Mapplethorpe, the controversial photographer best known for his depictions of radical sexuality?

Mapplethorpe became famous for his celebrity party pictures in the magazine Interview and his explicit photography of queer subcultures. But leading up to his death from AIDS in 1989, he focused on portraits of flowers. For Derek Conrad Murray, professor of history of art and visual culture, Mapplethorpe’s prolific flower artwork—more than 500 published works—trumpets the same themes as his earlier, more highly regarded work, noted for its coupling of classical beauty and risqué nature.

“The prevailing notion is that these were just a way to create something easily saleable,” said Murray, who documents his study of Mapplethorpe’s flowers in his 2020 book, Mapplethorpe and the Flower: Radical Sexuality and the Limits of Control. “I felt this was a critical blind spot.”

Mapplethorpe is one of few artists who could make flowers look beautiful but also subversive and dangerous, Murray said. “There's something provocative about them. They can make you uncomfortable. When you look at the various meanings associated with flowers, and then at Mapplethorpe’s BDSM images, or images of Black men, some of the deeper meanings are the same.”

*— *

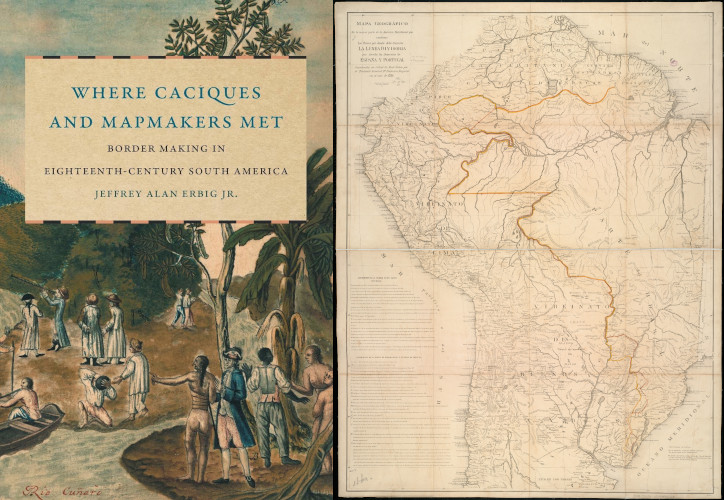

Latin American and Latino/x Studies

Border patrol

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Portuguese and Spanish mapmakers trekked across South America to create a border 10,000 miles long between the two colonial powers. Many histories assume that, by this time, the region’s Indigenous peoples were almost entirely under colonial control. According to Associate Professor Jeffrey Erbig, “this narrative is patently false.”

Erbig’s book Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America (University of North Carolina Press, 2020) shows that many Indigenous peoples remained autonomous, even as Europeans laid claim to their lands. Since oral histories maintained by native peoples focus on later national contexts, Erbig’s investigation drew on hundreds of archived colonial records from seven countries, many of them maps from the border-making expeditions. His analysis, he said, exposes these maps as “tools of colonial power, which purport to present images of truth, yet conceal many other things.”

The mapmakers often omitted the native territories of mobile Indigenous societies, Erbig said, at least partly due to their incompatibility with a sedentary European worldview. But the records show that colonists paid tribute to Indigenous peoples whose lands they crossed, and native leaders (“caciques”) leveraged Spanish and Portuguese competition to increase their own power. The historical erasure of the region’s Indigenous peoples continues to affect Native people, like those fighting for legal and cultural recognition in Uruguay, Erbig said. He hopes his scholarship will help support their cause.

*— *

Psychology

Baby steps

Parents often look to milestones to track their baby’s development. Instead of just ticking boxes, Professor Su-hua Wang seeks to better understand how babies develop. In her “Baby Lab,” Wang and her students use toys, books, and technology to study cognition—the process of learning—in infants and young children.

Babies as young as three months old show signs of cognition, said Wang. While they all actively observe the world around them, how they actually learn is shaped by culture and environment. In recent work studying how babies from different parts of the world learn to use toys, she’s found that parenting styles strongly influence the process, with sometimes striking differences that reflect cultural norms. For example, in the U.S., most parents lean towards exploration and hands-off approaches, versus in Taiwan, where most parents stress emulation and practice.

No one style is better than another, Wang said, but such cultural differences can make a one-size-fits-all approach to education problematic. Understanding the learning methods children experience in their early years can help educators adopt more effective teaching strategies. Wang hopes her findings—as applied in UCSC’s New Gen Learning, an initiative to support research on strengths-based learning—helps to address “this disconnect between home and school” that can disadvantage many children, especially those from historically underserved populations.

*— *

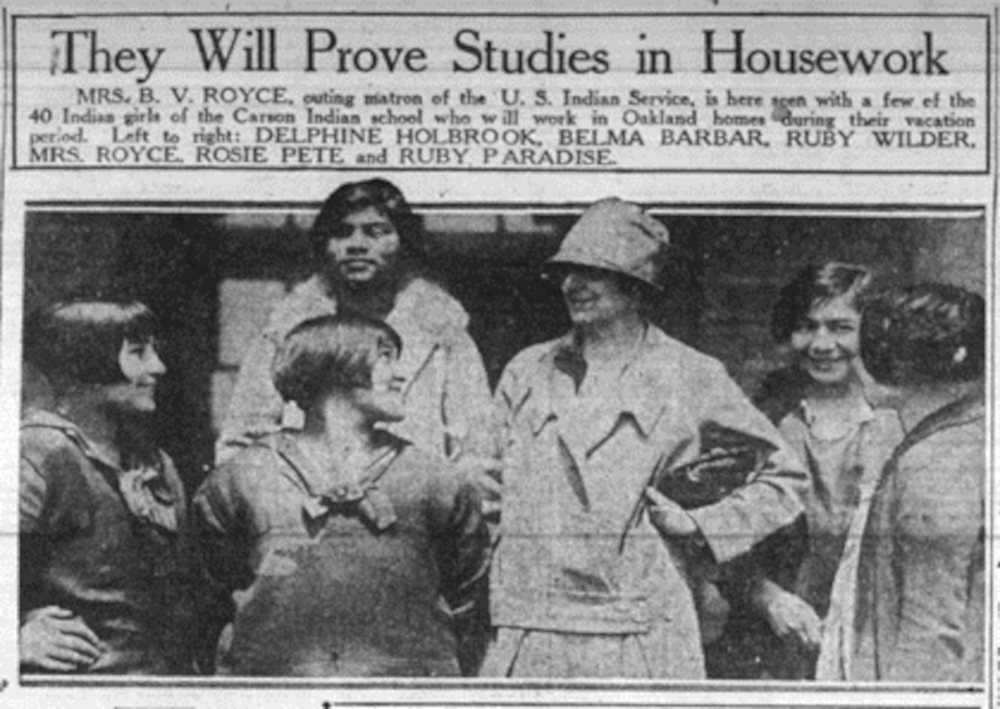

Feminist studies

Displacement

Between 1918 and 1942, as part of efforts to assimilate Native peoples, thousands of women worked for white, affluent families in the Bay Area as domestic help during holidays away from their Indian boarding schools. In hindsight, this “outing program” and similar ones throughout the country actually embodied a federal campaign of labor exploitation, according to Assistant Professor Caitlin Keliiaa.

In a government archive housed in San Bruno, Keliiaa unearthed roughly 4,000 letters, photos, and bank statements that trace the lives of the Native women placed in the Bay Area Outing Program. Her study of these documents reveals strict monitoring by the white outing matrons who oversaw them. Women suspected of sexual activity, for example, were “surveilled, managed, sent to detention homes, and sometimes arrested,” Keliiaa said. In rare instances, women ran away or even died while on placement.

The legacy of such outing programs, documented in Keliiaa’s book-in-progress, Unsettling Domesticity: Native Women and 20th-Century Federal Indian Policy in the San Francisco Bay Area, is not entirely negative. Program participants who stayed or returned formed a resilient Native community decades before more extensive migration to the Bay Area from reservations. Social clubs for Native people established by the outing program—to meet under supervision—also persisted, creating what Keliiaa calls “foundational spaces” for displaced Natives to build community and celebrate their tribal cultures.

*— *

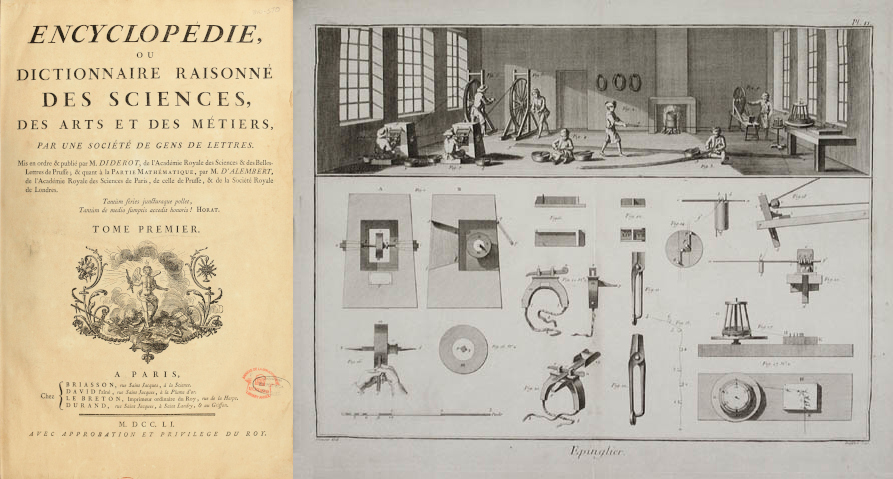

Film and digital media

The art of computing

Although many artists now use computers to make art, few know that art played a key role in making computers. According to Professor Warren Sack, art and craftsmanship laid the foundation on which computing and software design were built. In his book The Software Arts (MIT Press, 2019), Sack recounts how early figures in computing—like Charles Babbage, inventor of the first mechanical computer—were inspired by the 28-volume French Encyclopédie that catalogued the tools and step-by-step process of 18th-century crafts and trades, such as pin making, glass blowing, and tapestry weaving. “It all came from the workshops of artists and artisans,” Sack said.

An artist and software designer, Sack straddles the two disciplines, his work showcasing how computing can influence art as well. In The Translation Map, a 2003 installation created with artist Sawad Brooks for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Sack’s software routed messages in one language to a series of public discussion forums around the world, resulting in a collaborative process of translation. The artists then traced the pathways of how people worked together, producing translation “maps” that illuminated shared cultural and colonial histories—and enduring divisions. “If you accept the idea that computing is an art,” Sack said, “you gain a completely different way of looking at it.”

*— *

Physics

Particles from space

In 2018, a high-altitude balloon launched in Sweden ascended 40 kilometers into the atmosphere. While it drifted towards the far north of Canada, its 500-lb. payload of delicate sensors captured more than 130 hours of data intended to help untangle the mysteries of cosmic radiation.

Cosmic rays mostly include subatomic particles like neutrons and protons, which circulate throughout the galaxy at nearly light speed. Many of these particles are thought to be produced by pulsars, the “remnants of ancient stellar explosions,” said Professor Robert Johnson. But much about these galactic emanations remains unexplained, including the source of low-energy electrons, which make up a fraction of the rays.

To study these elusive electrons, Johnson, then doctoral-candidate Sarah Mechbal (Ph.D. ‘20; now at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron—DESY—in Germany), and John Clem at the University of Delaware collaborated on the NASA-supported mission, for which the UCSC team built AESOP (Anti-Electron Sub Orbital Payload)-Lite, an instrument capable of distinguishing electrons from positrons, their antiparticles.

The Earth’s atmosphere absorbs most radiation, making it difficult to measure—hence the high-altitude balloon to ferry AESOP-Lite near the edge of space. With the mission’s initial findings now published, the researchers plan to compare their data with measurements from similar sensors on the International Space Station and satellites deep in the solar system. These comparisons, Johnson said, could illuminate how our Sun’s radiation affects these particles from space.

*— *