Border patrol

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Portuguese and Spanish mapmakers trekked across South America to create a border 10,000 miles long between the two colonial powers. Many histories assume that, by this time, the region’s Indigenous peoples were almost entirely under colonial control. According to Associate Professor Jeffrey Erbig, “this narrative is patently false.”

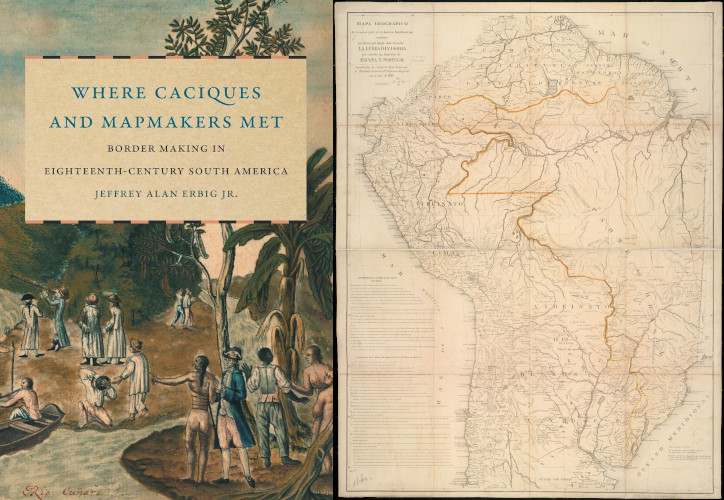

Erbig’s book Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America (University of North Carolina Press, 2020) shows that many Indigenous peoples remained autonomous, even as Europeans laid claim to their lands. Since oral histories maintained by native peoples focus on later national contexts, Erbig’s investigation drew on hundreds of archived colonial records from seven countries, many of them maps from the border-making expeditions. His analysis, he said, exposes these maps as “tools of colonial power, which purport to present images of truth, yet conceal many other things.”

The mapmakers often omitted the native territories of mobile Indigenous societies, Erbig said, at least partly due to their incompatibility with a sedentary European worldview. But the records show that colonists paid tribute to Indigenous peoples whose lands they crossed, and native leaders (“caciques”) leveraged Spanish and Portuguese competition to increase their own power. The historical erasure of the region’s Indigenous peoples continues to affect Native people, like those fighting for legal and cultural recognition in Uruguay, Erbig said. He hopes his scholarship will help support their cause.

*— *