Adaptable academics

Amid pandemic upheaval, flexibility finds opportunity

In March 2020, just after the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly turned the world upside down, Music Department lecturer Brian Baumbusch spent a sleepless night alternating between attending to his baby and anxiously pondering how he would manage during lockdown as a musician, composer, and leader of UCSC’s two Balinese gamelan ensembles (beginner and advanced). By the morning, he had devised a plan that would allow him to pursue his passion for composing polytempo music while supporting the Wind Ensemble at the same time.

Meanwhile, Ari Friedlaender, an associate researcher at the Institute of Marine Sciences and associate adjunct professor of ocean sciences and ecology and evolutionary biology, his research in Antarctica canceled, sat trapped on a cruise ship, desperate to get home to his pregnant wife. When he finally made it back to California, he was struck by the absence of boat traffic on the Monterey Bay. How might this newly quiet environment, he wondered, be affecting the humpback whales?

About the same time, Jennifer Parker, professor of digital arts and new media, was scrapping her plans to bring visiting artists to campus to brainstorm potential collaborations with faculty at the Genomics Institute. With everyone stuck at home, she started thinking, “How can we be alone together?” Drawing on her longstanding interests in new media and facilitating community, she decided to create a whole new world.

These faculty and others not only found resourceful ways to continue their scholarship, in many cases they created work and conducted research that the pandemic compelled and made possible. “People have learned a lot about their ability to be resilient,” said John MacMillan, then associate, now interim vice chancellor for research and professor of chemistry and biochemistry.

Dealing with it

In a year of unprecedented hardships—isolation, sickness, death, the trauma of racism, wildfires, political division—the burdens affected most but were not spread evenly. Pandemic restrictions were more onerous for some than others. While computer scientists apparently prefer to work remotely from home, it’s not as straightforward for lab and field scientists, humanities faculty barred from archives, artists without audiences, and anyone needing to travel. Working remotely is also much more difficult for people who had to—as many did—simultaneously take care of children, elderly parents, or other dependents.

“It’s a very uneven picture,” said Scott Brandt, professor of computer science and engineering and now former vice chancellor for research. “But many, many people suffered deeply because the work they do requires physical access to people or equipment. At the worst of it, there were profound impacts that were pretty devastating.”

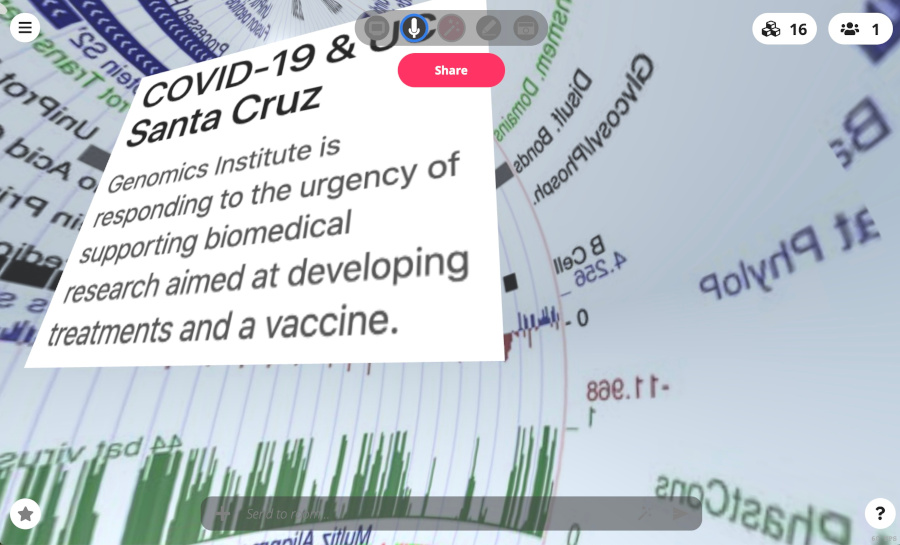

Yet despite everything, people in the UCSC community kept working. While the media spotlight shone on the rapid establishment of a COVID testing lab and the SARS-CoV-2 genome browser, faculty across all the campus’s five divisions rose to meet the challenges posed by the pandemic. Field researchers formed pandemic bubbles so they could safely stand side-by-side to roll 800-pound elephant seals onto a sling for weighing. Archaeologists caught up on publishing reports from past field seasons and used Google Earth to scope out potential sites for future seasons. The Mary Porter Sesnon Art Gallery mounted online shows complete with a virtual model of the gallery. And the UCSC librarians made more information available digitally than ever before.

In sync in isolation

Brian Baumbusch loves composing polytempo music, which uses different tempos for different players, but his compositions can be challenging for musicians, who naturally tend to synchronize with their neighbors. Pre-pandemic, Baumbusch solved this problem by giving each musician an ear bud with a pre-recorded click-track, essentially a personalized metronome.

Just before the pandemic, Baumbusch had written a polytempo piece for five players. During his sleepless night, he realized the new conditions were strangely perfect for creating a piece for a much larger ensemble. Everyone could record their parts at home using click-tracks, without having to fight the urge to get in sync with others. “The pandemic opened the door to a really complex musical idea that would have been much harder to do if we were all in the room together,” Baumbusch said.

First, he needed to find a large group of musicians. So, he texted his colleague, lecturer Nat Berman, director of the Wind Ensemble, on March 15: “Do you know the status of Wind Ensemble for spring?” Berman, who was wondering how he could teach the Wind Ensemble class remotely, immediately texted back, “Why? Do you want to write us a click-track piece we can record?” By March 23, just a week before the first (virtual) meeting of the Wind Ensemble, Baumbusch began composing.

Baumbusch built the score as the spring quarter progressed, writing all the parts in short fragments of a few seconds to a minute in length. Students signed up for fragments each week, downloaded the click-tracks, recorded their parts (usually on their cell phones), and sent them back to Baumbusch, who combined the recordings to create the piece.

If students were puzzled while recording the strange little fragments of music, Baumbusch won them over the first time he played them a finished section of the piece. “It was completely thrilling,” Berman said. “The students were really gobsmacked. They were extremely happy to hear themselves together, having been playing alone in bedrooms, especially because some of the fragments felt very abstract to them, as opposed to melodic.”

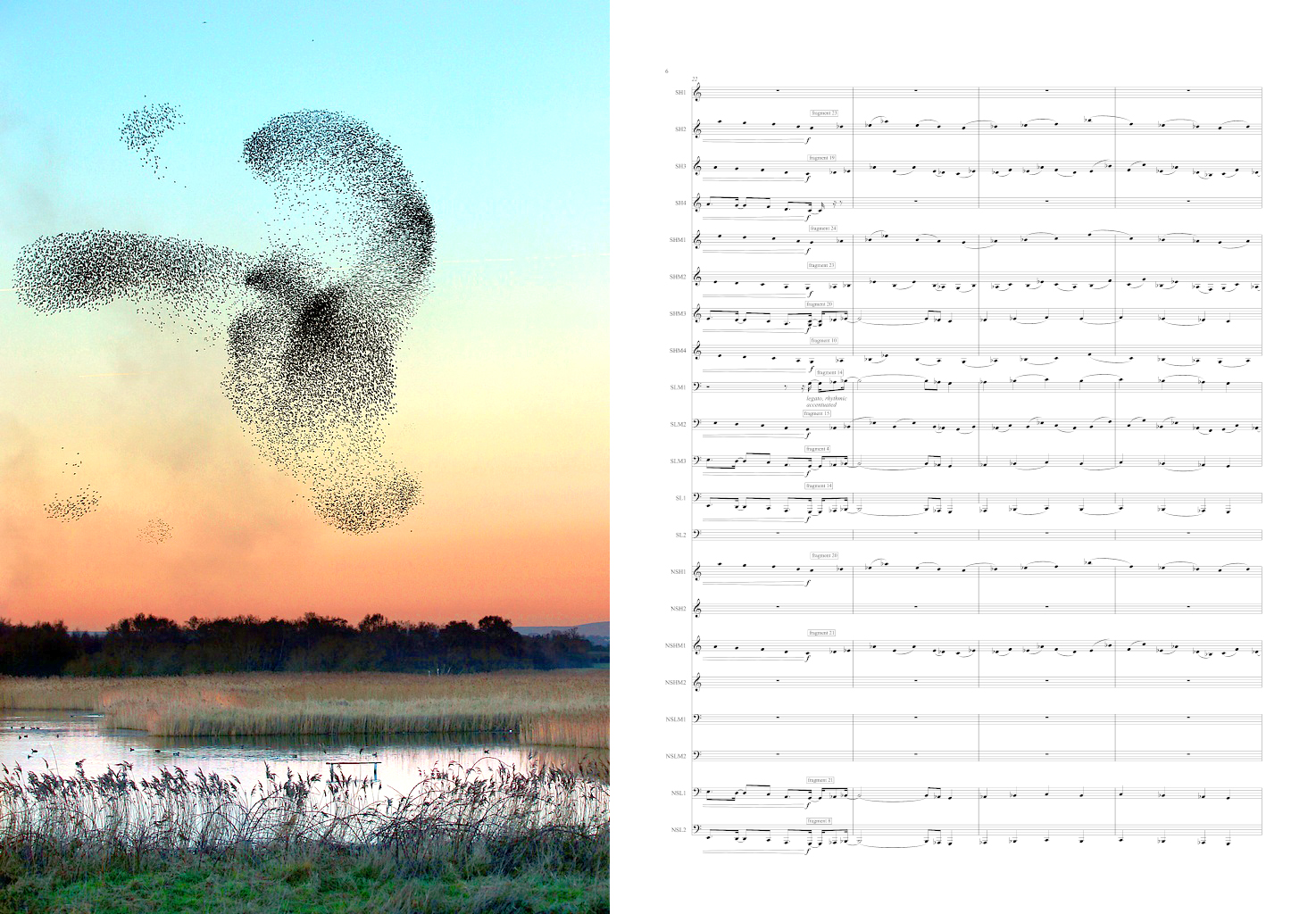

Despite its high-tech creation and production, the finished composition, Isotropes, brings to mind sounds of nature. One of its four movements is called Murmuration, a term that refers to flocks of starlings dipping and diving to create beautiful, ever-shifting shapes. “Every bird in a murmuration has its own pattern of getting there, but it still gets there,” Baumbusch said. In a similar way, each fragment of music, like each individual bird, moves at a different speed and direction, but they all come together to create mesmerizing, coherent music.

After the Wind Ensemble’s premiere of the piece in June, the Cal State Fullerton Wind Symphony began to record Isotropes. The music wouldn’t exist if shelter-in-place orders hadn’t isolated the musicians. “We took advantage of the unique circumstances,” Baumbusch said, “to create something we couldn’t have done any other way.”

Boats be gone

Early March found Ari Friedlaender in Antarctica, on that previously mentioned cruise ship. But unlike the other passengers, he wasn’t sightseeing—he was conducting whale research. Then, due to the quickly emerging threat of the pandemic, the ship was denied entry at its scheduled port in Chile and forced to find another, becoming the last ship accepted at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands before it shut down too. The ship’s passengers, including Friedlaender, waited in quarantine for 10 long days until the authorities shuttled them straight to the airfield for flights out. During the weeks-long saga, Friedlaender experienced firsthand the physical manifestations of stress, losing 20 pounds and developing painful back spasms.

Back in Santa Cruz at last, Friedlaender’s thoughts pivoted from his stress to that of humpback whales. Scientists have hypothesized that noise from boat traffic stresses whales by interfering with their ability to communicate with each other and find food. And now? Many fewer boats. Friedlaender realized he had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. He could measure the levels of stress hormones in Monterey Bay humpbacks during this lull, and then compare them to levels in the following year, when the bay returned to its normal noisy condition. He had to hurry, though, before boat traffic picked back up. The Marine Mammal Center in Moss Landing, one of the few organizations not shuttered by the pandemic, agreed to supply a boat and a captain.

Out on the water by mid-April, Friedlaender collected blubber samples from 45 whales. Graduate students—masked, socially distanced, and with staggered work hours—analyzed the samples in his lab. For both quiet 2020 and noisy 2021, the team plans to correlate hormone levels with records of boating activity in the Monterey Bay, as well as the sound recordings of the bay collected continually (really—listen here) by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. They’re also collaborating with Atlantic coast colleagues conducting a similar study on humpbacks in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Massachusetts.

Pre-pandemic, Friedlaender studied the foraging behavior of humpbacks, not their stress hormones. However, “If we can do something to show the impact of sound on local wildlife, we should,” he said. “I want people to think about how human activity affects these animals.”

Virtual community

The isolation brought on by the pandemic inspired a team assembled and led by Jennifer Parker, founding director of the OpenLab Collaborative Research Center. Their pandemic plan? To create a virtual reality gallery intended to encourage conversations among scientists, artists, and others. “The whole concept is brand new, spearheaded by this moment,” said Parker.

Before the pandemic, Parker had been working with Isabel Bjork and David Haussler, executive director and scientific director, respectively, of the Genomics Institute, on projects aimed at sparking in-person conversations around genomics and art. With in-person no longer possible, Parker reached out to Colleen Jennings, technical coordinator for digital arts and new media, and Shelby Graham, director/curator of the Sesnon Art Gallery, to explore potential virtual opportunities.

Online visitors to their creation, What Makes Us Human: An Art + Genomics Convergence, can explore three dozen projects, each covering topics as wide-ranging as genomics, evolution, beauty, race, and gender. “Trying to put those things in conversation with each other is challenging, but that’s what universities are for,” Parker said. While most projects were developed by people at UCSC, others were contributed by people likely to have been visiting artists if not for the pandemic, including Angélica Dass (Humanae), and Gina Czarnecki (the Heirloom Project).

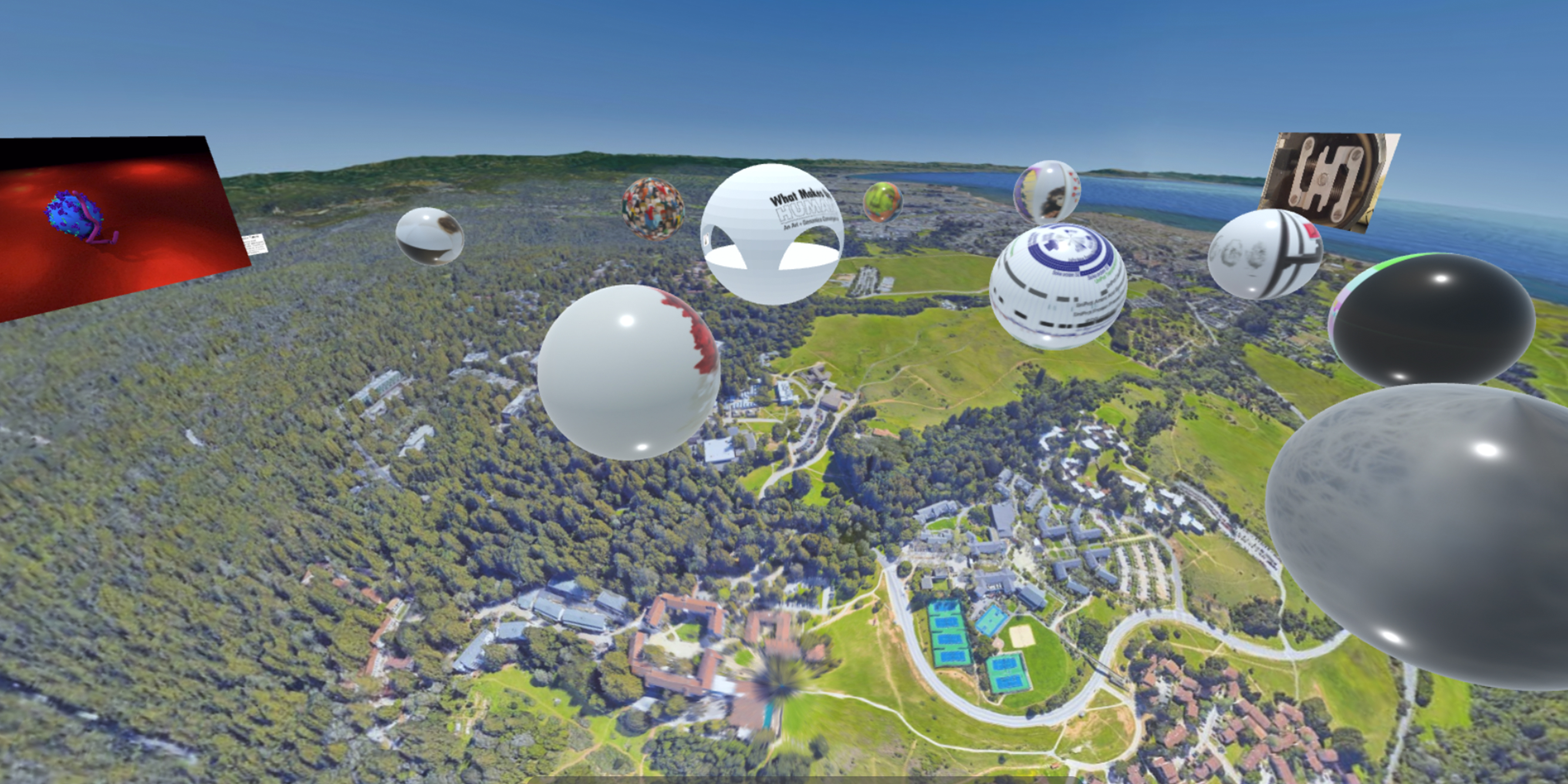

Each project has its own sphere that can be explored on a website or in a “virtual hub.” On the website, visitors can click on the spheres to learn more about each project. But much more is possible in a virtual hub. Visitors become avatars, able to move around in virtual space, look inside spheres, and interact with other visitors to share reactions to and discuss the different projects. Why spheres? Parker, a sculptor, prefers three dimensions to two. “The internet is trillions of pages, they are all flat, you have to scroll, and you don’t go inside of them,” she said.

The team had originally planned to install What Makes Us Human in the virtual Sesnon Gallery Jennings had already built, but they soon realized, Parker said, “the sky was the limit.” And that’s why one of the four galleries in the project’s virtual hub hung (see banner at top of article) in the sky above the Santa Cruz campus. “There’s no way we could have done this exhibition in the physical gallery,” said Graham.

Back to normal?

What will research at UCSC look like as the pandemic subsides—hopefully—in the face of vaccines and herd immunity? For many faculty members, just returning to campus will do much to bring back their “normal.” For archeologists and others who work in countries where vaccination is proceeding slowly, normal still may be years away.

Some adaptations to pandemic restrictions may stick, such as video conferencing in place of travel and an increased emphasis on digital lending through libraries. University Librarian Elizabeth Cowell said, “I always describe the library as having three locations: Science & Engineering, McHenry, and online. It will be interesting to see what that third presence becomes as we reopen to a hybrid environment.”

Parker thinks virtual hubs like the one she and her team created for What Makes Us Human will continue to grow in popularity because they let people experience a digital environment in a way that’s more satisfying and immersive than posting, clicking, retweeting, and scrolling. She has started teaching hub-building in her classes and is working with Bjork and others on campus to expand opportunities to participate and develop virtual hubs across the arts and sciences. “There is a digital renaissance happening, and the pandemic is pushing it farther and quicker than before,” she said. “It’s the beginning of what’s possible for us.”