A short story

By strong example and action, advocating for diversity in science

The Nobel Prize weighs about six ounces, but it feels much heavier if you’re female. Only 23 women—about 3 percent of the total—have won a Nobel Prize in the sciences. One of these select few is distinguished professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology Carol Greider, UC Santa Cruz’s first Nobel laureate.

Feeling the weight, Greider has wielded her influence as a laureate to advocate for increased diversity in the research community, working to help ensure women and other scientists from historically disadvantaged groups are free from discrimination and harassment. To this end, throughout her long career, she has spoken out, signed letters, authored op-eds, and joined working groups, in addition to serving as a committed mentor to many students.

“Carol takes this as a duty,” said Gisela Storz, a graduate student with Greider in the 1980s, now associate scientific director of the Division of Molecular and Cellular Biology at the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. “I've always admired her resilience and persistence—she has a voice that people pay attention to.”

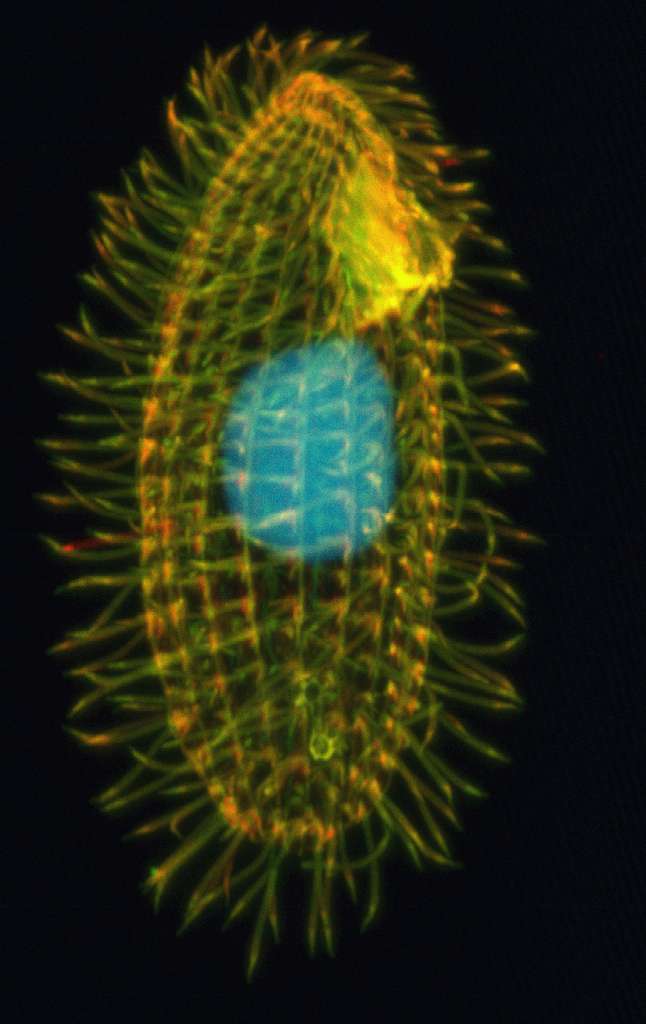

Greider’s resilience and persistence manifested early. In her hometown of Davis, Greider struggled in school with undiagnosed dyslexia. At UC Santa Barbara, where she earned her undergraduate degree, the late Beatrice Sweeney guided her into biological research. She next joined Elizabeth Blackburn’s lab at UC Berkeley as a graduate student studying a ubiquitous pond dweller, a single-celled, ciliated protozoan in the genus Tetrahymena.

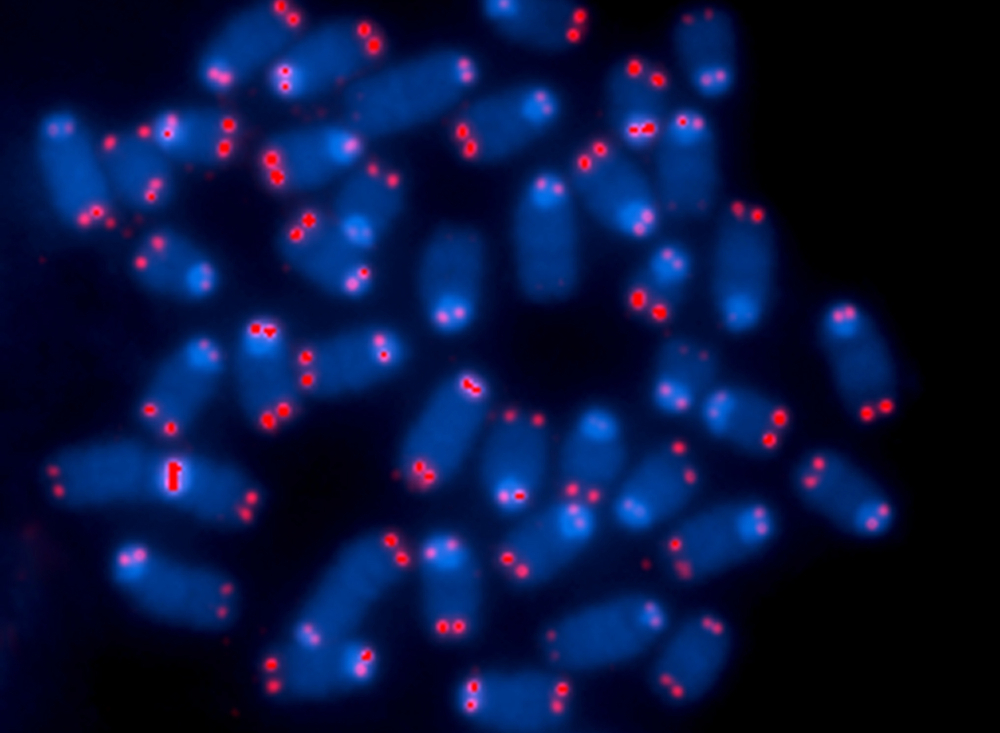

In this model organism for basic research, Greider helped find the answer to the long-standing question of how cells shield the genetic material in their chromosomes from growth-related degradation. During cell division and copying, chromosomes are protected by telomeres, repetitive DNA sequences that cap their ends. But with each division, telomeres get shorter. Greider—as a 25-year-old in 1984—discovered and characterized telomerase, the enzyme that makes sure telomeres don’t get too short. The work led to her sharing the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with her graduate mentor Blackburn and Harvard University professor Jack Szostak.

Greider’s research at UCSC continues to focus on telomeres and the fundamental mechanisms that maintain their length, work that has important implications for human health. Telomeres play a key role in cancer because “to continue dividing indefinitely, all cancer cells have to solve the problem of maintaining their telomeres,” Greider said. Knowing how this happens could yield new ways of fighting cancers. Our telomeres also get shorter as we age, and a better understanding of how this happens could help prevent or treat age-related diseases. “We’re not going to go from having general lifespans of 120 years to 200,” said Greider. “But the number of people who achieve 120 could be higher if we didn’t suffer from lethal age-related diseases.”

Many mysteries—like why some degenerative diseases are associated with shortened telomeres—still linger at the end of chromosomes for Greider and her new UCSC colleagues and students to solve. “We know very little about the actual regulation of telomere length,” she said. “We know how to make telomeres longer with telomerase, but we don’t understand how cells maintain this length day-to-day.”