BRIEF inquiries

All Divisions

Highest regards

When Cynthia Larive began her tenure at UC Santa Cruz in July 2019 as the new chancellor, she already knew she was joining a university with a commitment to impactful research. But a few months into the job, she got a reminder of just how highly the university is regarded. In November, the Association of American Universities (AAU), an exclusive group of universities at the forefront of research and academics, named UCSC as one of its newest members.

“AAU membership is such a great recognition of the ongoing contributions of our faculty, students, and staff,” said Larive.

The AAU includes only 65 member universities, chosen based on factors including faculty citations and awards, research funding, and commitment to undergraduate and graduate education. Together, AAU members work to shape educational policy at both institutional and national levels.

UCSC is one of the youngest schools invited to join the AAU, and one of only 15 without a medical school. “To be a university that does not have a medical school and be admitted to the AAU is really something to be proud of,” said Larive. The university’s strong focus on interdisciplinary research, undergraduate student success, and diversity and inclusion all help it stand out, she said.

Larive is no stranger to what it takes to run a successful research enterprise. At UC Riverside, Larive was both a professor of chemistry and served as provost and executive vice chancellor. Her research involved developing improved tools for chemical analysis used to study everything from human biology to food—one project had her characterizing the compounds in pomegranate juice.

“I’ve been involved in many collaborative research projects and worked with people who weren’t chemists to tackle important and complex problems,” said Larive, “And this informs the way I think about things.” This big picture perspective that she’s such a fan of is already prevalent at UCSC, she said, and AAU membership is a prestigious, very public confirmation of this. In recent years UCSC researchers have come together to launch large-scale, cutting-edge initiatives in genomics, global climate change, coastal policy, and agroecology, to name just a few.

Moving forward, Larive plans to fully support UCSC faculty in their hands-on approach to shaping the university’s research program—they’re the ones who can spot areas ripe for new research and collaborations, she said. “We’re on a great trajectory already.”

Psychology

You are welcome

Associate professor of psychology Rebecca Covarrubias spent nine long years in Tucson studying at the University of Arizona. While she often visited home, her family visited the university to drop her off for her freshman year, and once again when she graduated with her doctorate. The university was so unfamiliar to them as to be “almost unwelcoming,” she said. “Home was only a two-hour drive away, but it felt like worlds apart.”

It was initially unfamiliar and hard for Covarrubias, too. She now aims to make this cultural mashup—a challenge for many “first-gen” college students like herself—more visible and less stressful.

While universities value independence and intellectual exploration, first-gen college students from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds are often balancing—and are strengthened by—family obligations. They care for siblings, translate at medical appointments, or offer financial support. “A university culture of independence and separation largely renders these connections invisible,” said Covarrubias, whose research focuses on issues of identity, culture, health, and educational quality/access for underrepresented and diverse individuals.

To help bridge the divide, Covarrubias works with the Hispanic-Serving Institutions initiative’s Sense of Belonging team to organize a free, bilingual, half-day conference for low-income, first-gen families to meet parents of graduated students with similar backgrounds. Institutions must also change, said Covarrubias, who serves as faculty director of the Student Success Equity Research Center. “We can give students tools to navigate academia, but we also need to create a culture that reflects students’ varied backgrounds and ways of being.”

Biomolecular Engineering

From volcanic puddles

A prevalent theory posits that simple organic molecules initiated a primitive version of metabolism in hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean, leading four billion years ago to the origin of life. Professor of biomolecular engineering David Deamer thinks otherwise.

"There are layers of difficulty trying to get reactions to work in underwater vents," Deamer said. As explained in his book Assembling Life (January 2019), Deamer’s alternative theory suggests that these critical molecular transformations occurred under more favorable conditions: in hot springs associated with volcanoes.

Small pools fed by hot springs would have contained mixtures of nucleotides—the building blocks of DNA and RNA—mixed with lipids, the primary component of cell membranes. When the pools evaporated, concentrated films of nucleotides and lipids would form on mineral surfaces. Under these conditions the nucleotides spontaneously link into DNA and RNA, a reaction demonstrated in Deamer’s lab, which, incidentally, led to a patent. Ongoing wet-dry cycles selected for chemically stable, lipid-encapsulated nucleic acid chains, creating the molecular seeds for the emergence of living organisms.

Deamer and research associate Bruce Damer tested the idea by adding nucleotides to water samples from natural hot springs in volcanic sites around the world. Analysis of the mixtures cycled through wet-dry phases revealed microscopic vesicles containing polymers. Although not alive, these “protocells” are an essential first step toward molecular systems that can initiate Darwinian evolution, Deamer said.

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Bat cave blues

White-nose syndrome has killed millions of bats, cutting a deadly path across North America. Originally confined to the eastern United States, the disease is now affecting bats in Washington, Oregon, and California.

Caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the disease attacks bats when they are hibernating, said Professor Marm Kilpatrick. The disease appears as a white powder on the bats’ skin, hence its name.

Kilpatrick, a disease ecologist, was interested in how the fungus spread between and among different bat species never observed in social groups or in contact with each other. To study this, Kilpatrick and Joseph Hoyt, then a doctoral student (and now an assistant professor at Virginia Tech), daubed a UV fluorescent powder, which mimics the fungus, on individual bats. Tracking the dust’s spread in the caves and to other bats showed how “cryptic” connections—shared contact with part of the cave or very brief contact with other bats—play a key role in transmission of the fungal pathogen. The mechanism is similar to how contact between strangers coming together in planes or subway cars, or in stores or cafes, might spread human pathogens, like the coronavirus in the Covid-19 pandemic, Kilpatrick said.

The overall prognosis for bat species in North America is dire, said Kilpatrick, who is also researching potential treatments. The northern long-eared bat, for example, has suffered population declines of more than 99 percent; three other species have also been heavily affected but will likely persist. “The disease has caused massive, enormous declines,” Kilpatrick said.

Digital Arts & New Media

Kanye? Or Not?

Imagine a tabletop game where cards illustrated with faces stand in racks before you and your opponent. You’re ready to take turns asking yes-or-no questions to guess each other’s unseen cards. Wait…what’s this? All the faces depict black men, and half are Kanye West.

This is ‘ye or nay?, a game/artwork created by assistant professor of digital arts and new media and critical race and ethnic studies A. M. Darke, a conceptual artist and activist who designs tools for social intervention. A work in progress with illustrator Tajae Keith, ‘ye or nay? is Darke’s satirical reimagining of Guess Who?, the classic game in which the first question commonly asks: male? (or female?). Darke replaces this question in ‘ye or nay? with one based on a “far less ridiculous binary”: Kanye West? (or not Kanye West?).

By requiring players to describe and differentiate among black men, ‘ye or nay? provides opportunities for them to reflect on their perceptions and biases in an engaging way, Darke said. But the main goal of depicting black faces is so black people can see themselves represented in a broader way than in mainstream, white-dominated culture, they said. “‘ye or nay? is just as much about celebrating black male beauty as it is about examining the language we build around blackness.”

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Better biosensors

Efforts to improve sensors that can measure biological substances in or on the body—for monitoring glucose in diabetics, for example—face the challenge of working at the pH (hydrogen ion) levels found in living organisms. Human blood, sweat, and tears typically have a pH of around 7. “Unfortunately, many metals that are good at measuring substances like glucose are only effective at pH 11,” said professor of electrical engineering Marco Rolandi.

Rolandi and his team have now overcome the pH challenge. Their research leading to the patent-pending invention was published in July 2019 in the Nature journal Scientific Reports. By boosting the immediately surrounding pH, their millimeter-sized, metal-based biosensor can measure glucose levels in a solution that mimics body fluids.

The group created the biosensor by depositing small amounts of different metals on glass using a process called photolithography. Palladium metal increases the nearby pH by drawing hydrogen ions out of solution. The higher pH levels allow cobalt-oxide contacts next to the palladium to react with glucose and change oxidation state; the device measures the resulting current to determine the glucose concentration.

The metal-based biosensor could offer advantages over current glucose monitors for diabetics, which typically last only months as the enzymes on which they rely eventually degrade. In addition, such a device implanted in the body may be less tissue-reactive, Rolandi said.

Astronomy and Astrophysics

Space sanctuaries

Natalie Batalha thinks there’s life on other planets and she’s made it her mission to find it. Before joining the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics in 2018, Batalha helped lead NASA’s Kepler Mission, which surveyed a section of the Milky Way Galaxy and discovered more than 2,600 new planets. Many were dubbed “Goldilocks planets”—planets roughly the same size and temperature as Earth, making them ideal places to search for liquid water and life.

Now, Batalha wants to characterize the atmospheres of some of those planets. She believes scientists will be able to detect unique biosignatures in the atmospheres surrounding planets that host life by learning what’s typical when it comes to planetary atmospheres. “I think living worlds will stand out like a sore thumb,” Batalha said.

Batalha will collaborate with researchers from around the world to collect this atmospheric data using the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2021 and orbit in space for five to ten years. In anticipation of that launch, Batalha is busy analyzing data on new planets being observed through a telescope at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. The basic information collected there helps her choose which planets to focus on with the Webb mission.

Searching for extraterrestrial life is not only driven by pure curiosity, Batalha said, but also questions about what it takes for planets—including Earth—to sustain life. “We need to make sure our own planet continues to be a habitable sanctuary for humanity,” she said.

Music

Discordant compositions

Poets consider music to be humankind’s universal language. But deep divides of race and income at times split its makers—at least those who were members of the American Federation of Musicians (AFM)—in the early 20th century. Leta Miller, professor emerita of music, discovered a piece of this troubled past in San Francisco’s history, where black and white musicians formed separate, competing union local chapters.

The conflict in San Francisco came to a head in 1934 when the black Local 648 sued their white counterpart, Local 6, for attempting to control all gigs. State laws eventually forced the two to merge in 1960. But Miller found that similarly segregated union locals were commonplace across dozens of U.S. cities—and some even persisted into the early 1970s. “I was quite astonished at how many there were,” Miller said.

Supported by a 2019–2020 Dickson Emeriti professorship, Miller is now working on a book about segregation in musicians’ unions across the nation. While the separation was no doubt rooted in racism, black musicians in many cases actually chose to form their own locals. Miller found that, apart from promoting identity and community, doing so allowed them to set their own rates—sometimes undercutting the white competition. Each local also garnered a seat at the AFM national convention, so “having their own local ensured that black musicians were guaranteed a voice at the meeting,” Miller said. “That was probably very important.”

History

Transformed by occupation

Okinawa, a tiny speck in the vast Pacific Ocean, plays an outsized role in American history. For 75 years, since the end of World War II, the United States has occupied this smallest of the five main islands of Japan with a string of strategically significant military bases.

The consequences of this occupation are the focus of the Okinawa Memories Initiative, a sprawling oral history project led by associate professor of history Alan Christy. The work aims to document and understand the dramatic social changes that occurred as Okinawan society rapidly transformed from very traditional to very modern.

The research chronicles, for example, the impact of a surge in high-tech entertainment and media services. Based on this business focus, Naha, the island’s main city, is poised to become a major driver of the Japanese economy over the next decades, Christy said. “The media environment is incredible for a place its size,” he said.

The project, which began with the donation of a cache of photographs taken by Charles Eugene Gail, an American military officer stationed on Okinawa in the early 1950s, has since broadened its scope to encompass the entire occupation, from 1945 to the present. To uncover the personal stories of Okinawans during this time of major transformation, Christy and collaborators use interviews, photographs, and archival records found in both Okinawa and Washington, DC. “The changes that happened here are historically significant, and well worth understanding,” Christy said.

Environmental studies

Urban farming

Even in a city, a wildlife haven might be just around the corner. In urban gardens throughout Santa Cruz, the Monterey Bay Area, and Santa Clara County, Stacy Philpott, professor and director of the Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems, has cataloged a wealth of species, at least 60 types of bees, 25 of spiders, 18 of ladybugs, and about 60 of birds.

Philpott and her research group study how differences in urban gardens, like their “messiness” and the number and types of nearby trees and shrubs, affect their biodiversity. In general, the group finds that what’s good for biodiversity is good for human gardeners too. Their experiments suggest that gardens with more biodiversity have more effective pollination and natural pest control.

Right: In a "tidy" garden—also in Monterey, while wood chip mulching might look nice, it can discourage nesting by bumblebees and visits by other pollinators. But it could attract other beneficial arthropods, like spiders. Credit: Stacy Philpott, with permission.

It’s also clear that urban gardens can be invaluable to the people who use them. Surveys of community members who work these gardens show that many garden as a way to spend time outdoors, relieve stress, and hang out with their families. For some, having access to a space to grow produce provides a vital way to put food on the table. A substantial number of lower-income gardeners surveyed experience some food insecurity, Philpott said. ”There's a lot of demand for space in cities and many interests competing for its use,” Philpott said. “Our research shows that gardens are important spaces.”

Earth and planetary sciences

Making the earth move

Modern methods of extracting fossil fuel from the ground also bring up vast amounts of highly contaminated water. The safest way to dispose of that toxic wastewater is to pump it back underground, but that can disturb faults and trigger earthquakes. “People make earthquakes by shoving water into the ground or by pulling water out,” said professor of Earth and planetary sciences and induced seismology expert Emily Brodsky, who has made it her mission to understand this phenomenon.

To more closely investigate how wastewater injection triggers earthquakes, Brodsky and then researcher and lecturer Thomas Goebel (now an assistant professor at the University of Memphis) analyzed data from 18 drill sites around the world. Their findings, published in the prestigious journal Science (August 2018), overturned conventional wisdom about the safest place to inject wastewater. Oil companies typically avoid injecting into deeper, harder basement rock that contains most seismic faults, opting instead for shallower, softer sedimentary rock. Brodsky and Goebel’s evaluation of injection depths and affected rock types revealed that the sedimentary strategy triggered more earthquakes and ones of higher magnitude. “Sedimentary injections are more dangerous than basement injections, the opposite of what everyone thought,” Brodsky said.

Sedimentary injections can transmit pressure up to 10 kilometers away, increasing the chances of disturbing faults. Oil companies are better off injecting into basement rock, especially if they can pinpoint areas free of major faults, Brodsky said.

Biomolecular Engineering

Boosting blood cells

Approved in 1998, the drug sildenafil citrate—better known as Viagra—offered men with erectile dysfunction a welcome alternative to the invasive solutions then available for their non–life-threatening but life-altering condition. As urban legend has it, Viagra’s developers initially tested it as a drug to lower blood pressure and were surprised by its notable side effect. The rest is history.

Now, researchers led by professor of biomolecular engineering Camilla Forsberg have found another potential use for the infamous “little blue pill.” Recently published in Stem Cell Reports (October 2019), their work showed that the drug enhanced the effect of the immunostimulant plerixafor, boosting the blood stem cell mobilization (movement from bone marrow to bloodstream) critical to the high-risk transplants used to treat—and potentially cure—patients with blood-based cancers and other immune-based disorders. Extracted from donors or patients themselves, the mobilized stem cells are “transplanted” into the patient to reconstitute their blood after a course of high-dose chemotherapy and/or radiation kills off both normal and malignant cells.

The results suggest that the new combination may provide a more rapid and effective means of collecting stem cells than older, often unsuccessful methods needing multiple injections over several days. “We try to provide paradigms for clinicians to work with,” said Forsberg, whose wide-ranging research focuses on the molecular biology of hematopoietic stem cells. “The lab is where we can do new and crazy things and make discoveries.”

Environmental Studies

Not just plants

Walking across the UC Santa Cruz campus, the towering pines and wildflowers are easy to spot. Less obvious? The fungi that call these plants home. But those fungi play key roles in the campus ecosystem. Just as a human body teems with microorganisms, all plants host fungi that can help them thrive, cause disease, or anything in between, according to professor of environmental studies Gregory Gilbert. “Fungi really shape everything plants do,” he said.

Gilbert, along with professor of ecology and evolutionary biology Ingrid Parker, has collected thousands of plant samples from around UCSC and extracted their DNA to study what fungi they’re infected with. Their goal is to understand which species of fungi infect which plants, and how those infections spread over time. Santa Cruz is an ideal place to study these interactions because of the range of climate conditions and plant diversity, Gilbert said. “We have this amazing living laboratory campus.”

When a new disease-causing fungus invades an ecosystem, there is often sparse science to inform—and frequently little time to determine—what might be done to limit its spread and impact. Gilbert hopes his research, besides illuminating the less obvious, will help inform such actions by improving our understanding of the biology through which plants and fungi interact.

Writing program

Success before tragedy

To create the Peoples Temple in 1955, its founders merged religious ideology with a vision of a world that transcended race and social class. Twenty-four years later, more than 900 of the group’s members lay dead, their bodies decomposing in the Guyanese jungle heat.

The group’s written records both reflect and—importantly—shaped its tragic path, said teaching professor of writing Heather Shearer. Shearer began researching the group’s documents expecting to find evidence of “brainwashed cult members,” she said. “But I saw a really different picture.”

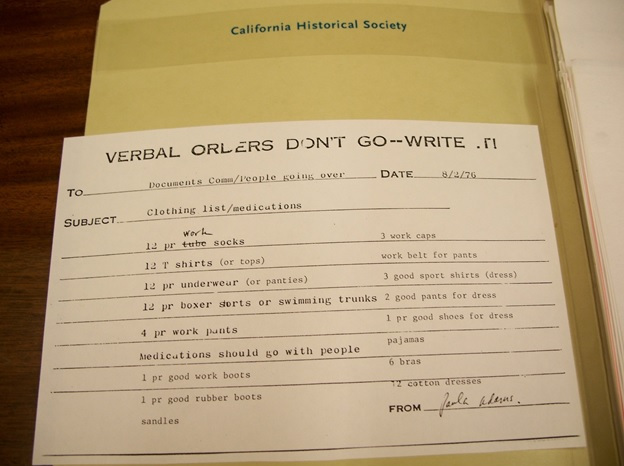

Ninety-six boxes of letters, pledges, and checklists—some on memo pads printed with the header “Verbal orders don’t go—write it!”—bear witness to the group’s meticulous planning and utopian achievements: a racially integrated church in 1950s Indiana, communal housing developed in Northern California, and members’ excitement as they built Jonestown. “They’re known for dying, but let’s not forget what they accomplished,” Shearer said. “It’s impressive how organized they were, and how the writing helped them organize.”

Dismissing them as a cult denies what we learn from their written communications, Shearer said. “They had noble aspirations. The documents show how much they wanted to build a better society and how hard they worked for it.”

Economics

Fertilizing development

In the fight against global poverty, rigorous field research can provide important insights. This conclusion determined the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, awarded to three researchers—Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, and Michael Kremer—for their pioneering efforts in applying this approach to the study of economics in developing countries. This rigorous, quantitative methodology also drives the work of associate professor and development economist Jonathan Robinson.

Robinson’s collaborative research with Duflo and Kremer, among others, focuses on understanding why potentially life-changing agricultural practices remain little used in many impoverished areas. For example, while the use of fertilizer has increased dramatically in countries like India, smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa haven’t followed suit. The weak uptake there may be due to different environments and crops grown, or inadequate education, but another barrier could be the high cost of access related to poor infrastructure.

In a recent study, Robinson and collaborators quantified how poor roads and distance from a fertilizer retailer correlate with decreased fertilizer usage and individual farmer productivity in Tanzania. Their results directly connect the increased costs of obtaining fertilizer for farmers in more remote villages with reduced earnings from what they grow. “Farmers ultimately choose to adopt inputs like fertilizer based on profitability,” Robinson said. “Even if fertilizer increases yields, farmers may reject it because the costs of access are too high.”