Turn me on I'm a radio

Pioneering art along the electromagnetic spectrum

Just as the sun set on the eastern Icelandic town of Seyðisfjörður, the operator slipped on her headphones and began to broadcast the sounds of the night rising close to the Arctic Circle. If you had been in the right place, and tuned your radio to just the right frequency, you might have heard it: a rise and fall of static, followed by mournful, musical sounds. A foghorn, maybe, or the call of a creature from the depths of the sea? And, then, a calm, precise series of spoken “dits” and “dahs.” A transmission from a sinking ship? A beacon from some faraway place? If you knew Morse code, you’d understand the message: “This is the evening of the year. Cheer us for the darksome hours.”

Translating the haunting, ambiguous noises is harder. Are they whale songs? Train whistles? They elicit the vertiginous feeling of driving alone at night through an unfamiliar landscape. This ambiguity, and the questions it provokes, inspire radio and transmission artist and UC Santa Cruz film and digital media assistant professor Anna Friz. Throughout her career, Friz has sought ways to expand what we think of as radio, making pieces like this one, Radiotelegraph, which contains sounds including ones made by the radio waves themselves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves that travel through the air and make their way to the antennas of our own radios, where they are transformed into the sound waves we hear. But along the way, the radio waves can interact with each other, the landscape, and anyone that encounters them, creating both new sounds and, for Friz, new ideas.

Friz’s work includes these waves, and more. “Radio is often described as disembodied,” Friz said. “But to me, radio also includes a tremendous amount of infrastructure.” That infrastructure includes the energy that’s needed to send radio waves gliding through the air, the hardware that goes along with this, and the people who construct, tune, and play with the transmitting and receiving instruments. It also includes the surrounding world, in which sunspots create interference, and a clear night can bounce signals off the ionosphere and into unexpected, distant receivers. Radio can also connect deeply with place and history: in 1906, workers connected the first undersea telegraph cable from Europe to Iceland through the narrow fjord by the town of Seyðisfjörður, where Friz performed Radiotelegraph. “Making these things a little more apparent to people is really interesting,” she said.

Friz has transformed the way artists use and think about both radio and other wireless technologies, said Jeff Kolar, a fellow sound artist and radio producer who commissioned Radiotelegraph for Radius, an experimental Chicago-based broadcast platform. Friz simulcast the piece from both her low-watt FM transmitter in Iceland and the Radius transmitter in Chicago, creating the impression for its temperate-zone audience of a dispatch from the far north. Friz’s substantial body of work includes similar broadcasts heard on national public radio in countries such as Germany, Australia, and Austria, as well as radio-based installations that use sound to explore the dynamic interaction of radio with setting and listeners. “Anna is one of the first people to really push radio art off the traditional radio format and think about it as a way to present sound in art exhibitions,” Kolar said.

Radio as medium

Friz’s radio rapport began in college, while working at a Vancouver, B.C., community radio station, doing everything from sound engineering to hosting a weekly radio show. She had always been interested in performance art—at one point, she taught herself how to play the accordion so that she could join a clown band—but it took a few years at CiTR 101.9 FM before she realized that she could make radio her medium.

The sounds that interested her the most were the very ones that most radio broadcasts scrub from their airwaves: speaker distortion, a DJ’s rattling inhale, other accidental squeaks and fumbles. To Friz, these sounds aren’t mistakes. Instead, they remind us “that people are expressing emotions into microphones,” and what you hear is a circuit of relationships crossing through people, their surroundings, and the technology they use. “The noise tells us something about those relationships,” she said. “It offers the potential for something to happen.”

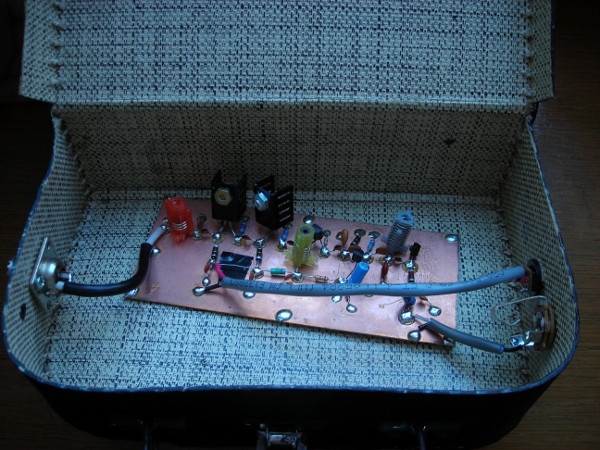

To capture sounds for her compositions, Friz taps a wide variety of sources. She’ll record the sound of radio interference. She might use walkie-talkies, or very low frequency (VLF) recorders, or transmitters and instruments that she’s built herself. And then she might loop in interviews, scripted dialogue, or her own voice. Each piece is a little experiment, a world of its own. “I’m definitely creating a landscape out of all of these different sorts of electromagnetic signals,” she said.

In her installation work, Friz seeks to create an immersive experience for listeners. Take Respire, for example, a piece she first presented in 2008 in Lisbon, Portugal, for the RadiaLx Festival, and later in Canada, Estonia, Chile, and the U.S. Picture hundreds of handheld transistor radios hanging from the ceiling on wires and swinging like mobiles as listeners enter and move about a darkened room. Attached blue bicycle lights transform the radios into constellations in the night sky. The interacting electromagnetic waves cause the receivers to emit strange, transient sounds—chirps, hums, and other textures that blend into a rich, evolving sonic experience. “People sensed that the array was responsive,” Friz said. “You feel you are in an environment that is changing, that is unstable, that can tell you are there.”

Friz voiced this seemingly living array with recorded sounds of breathing and interviews of witnesses to a shooting. In its largest presentation as a featured piece in Nuit Blanche, a 12-hour overnight art event staged in 2009 by the city of Toronto, the installation involved 250 radios and a four-part composition flowing through four FM microradio transmitters.

Respire, which explored how people hear and feel distance and how empathy might be wirelessly communicated and felt, grew out of Friz’s doctoral project in communication and cultural studies at Toronto’s York University. The piece suggests that the noise, breathing, and voices don’t distance listeners from what they’re hearing, but instead make them more aware of the connections among themselves and the voices they hear, and the radios and the sounds they produce.

“Radio art speaks to the idea that you’re a human body, and you’re also an antenna attached to the ground,” Kolar said. “We’re always bathed in these waves, whether it’s your WiFi or the radio waves of all the thousands of songs that are being played at that moment.” The magic comes from being in the presence of the art itself, taking in the full sensory experience of interacting with the waves and the devices transmitting them.

Making the ethereal tangible

Radio art is part of a broader category called transmission art. Artists creating in this space intentionally incorporate electromagnetic waves into their work—from extremely low-frequency radio waves to high-energy gamma rays, said Galen Joseph-Hunter, author of Transmission Arts: Artists and Airwaves and executive director of Wave Farm, an Acra, New York-based nonprofit that focuses on experimental transmission art. The genre makes “the ethereal tangible,” Joseph-Hunter said, allowing the audience to experience physical space through audio and visual representation.

Central to the ephemeral qualities Friz strives to bring to this felt experience is empathy. The theme plays a key role in The Joy Channel, a collaboration between Friz and composer and sound artist Emmanuel Madan. The work imagines a future world in which radios can broadcast pure emotion, and nomadic groups have developed a form of tele-empathy. The multiyear project, first commissioned by Radio Tesla, was originally performed live in Berlin in 2008, later broadcast in Austria, and in 2018 became available in a final version as a digital download from the Vancouver-based label IO.SOUND.

For the project, Friz and Madan developed a script as well as sonic elements to create a sense of optimism about the future of radio. Madan said that they were inspired by the work of science fiction authors whose envisioned futures blend harsh reality and hope. The heart of The Joy Channel is the connection between sound and human emotion: “Both can represent fields of resonance, commonality, and community,” Madan said. The Joy Channel, he said, “uses sound as a tangible representation of the kind of community and solidarity that we see as essential to a brighter future.”

Community is a theme that runs through much of Friz’s work. Many pieces require multiple collaborators and participants, from fellow sound artists to the radio platforms in more than 30 countries where her work has appeared, as well as the exhibitions and agencies that have provided homes and funding for her work. She continues to be involved in Skálar, a sound art and experimental music collective in eastern Iceland, where Radiotelegraph was created. The Icelandic connection led to a recent appearance in the 2018 New York Times Magazine Voyages issue, which innovatively coupled images with audio from destinations around the world. Friz and her partner, Konrad Korabiewski, Skálar founder and UCSC research associate, traveled around Iceland with a photographer to collect sound for their contribution.

Desert soundscapes

After working, traveling, and performing across Europe and the Americas, Friz has found a home in Santa Cruz, where she is collaborating with colleagues in film and digital media, as well as soaking in the influence of UCSC’s ecology and environmental research. These connections are key to her latest project, a series of works focused on the landscape of the northern Chilean deserts. Here, pyramid-sized piles of mining tailings can be seen from satellites, plastic bags flutter from miles of fences, and the infrastructure of roads, cables, and pipelines radiate from copper and lithium mines. Interspersed with all this is the high-altitude beauty of arid plains, distant peaks, and the plants and animals that struggle to survive there. Friz aims to capture this complex landscape with a combination of audio, photography, and videography in her project We Build Ruins.

In these high deserts, Friz is recording sound with multiple microphone setups, including a contact microphone that records waves traveling through solid objects, an underwater microphone, and a VLF receiver that can detect activity in the ionosphere. She also takes photos and records each day’s experience in a field diary. Assisting her is Chile-based artist Rodrigo Ríos Zunino, who takes photos, videos, and additional audio recordings. Together, they’re exploring the expanse of the landscape and the long-lasting footprint of the mining activity that fuels the area’s economy. Friz points out that the extracted materials are part of many of the recording instruments that she has used throughout her career, and the digital devices that many of us use every day.

Listen and you may hear truckers on the Pan-American Highway on their CB radios. You might hear the wisps of evaporation from salt ponds, the rumblings of a distant volcano, the crackling foil from a pile of contraband cigarette packages, the rustle of the plastic bags entwined in fences in the relentless desert wind. “The desert appears in my memory as a platform for things to disappear,” said Ríos Zunino, “a place to smuggle, hide, and lose what we do not wish to see anymore.” Friz premiered her first piece from the initial fieldwork, called Radiation Day, at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria, in 2017, and performed it again in 2018 at a music festival in Quito, Ecuador.

In addition to capturing the distance and degradation with electromagnetic waves, Friz aspires to show the human connection. To this end, she is weaving an “earth suit” out of cassette tape and plastic bags, Andean wool, and alpaca yarn. She intends to use the suit as a sculptural element in future pieces, which will include installations, performances, and possibly publications. Combining visual and narrative elements, she hopes, will create many touchpoints through which listeners and viewers will find ways to connect. Friz knows that her work is often “noisy,” but the purpose is to invite people in. As a composer, she said, “I need to give people space to pay attention in the way that I hope they will.”

In many cases, Friz doesn’t know who hears her work. It could be someone walking through one of her installations or sitting in the audience of a performance. But it could also be someone on a solitary journey, who, at the right time, in the right place, eases across their radio dial. They may hear strange musical noises or a screech that makes them question what they’ve heard, or soft breathing or a voice that brings some comfort. Or they could hear the last lines of the Morse code in Radiotelegraph, even though they can’t translate them: “We remain together. We are here for the night. Confirm. Wait. End transmission. Closing station.” Then, maybe feeling that the distance between them and everything else has shortened, they journey on into the coming night.