No detail too small

Studying the oceanic carbon pump at the atomic level

Every year, humans spew tens of billions of metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through industry and by burning fossil fuels. Carbon that lingers in the air can trap heat from the sun, potentially contributing to destructive global warming. It could be a lot worse. Fortunately, the Earth is blessed with a series of massive “pumps,” natural processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere and lock it away for centuries or millennia. The biggest pumps are found in the oceans, which is why many scientists have devoted their careers to understanding the flow of carbon from the air to the sea.

The future climate largely depends on the continued power and efficiency of the ocean’s carbon pump, so every gear and cog matters. Many scientists study the big-picture movement of ocean-based carbon, including the gigatons of carbon taken up by microscopic algae, also known as phytoplankton. Matthew McCarthy, UC Santa Cruz professor of ocean sciences and codirector of the Stable Isotope Laboratory, is one of a growing number of researchers who study the pump in finer detail—in his case, down to the atomic level.

McCarthy and his team track naturally occurring isotopes of carbon, atomic-level variations that can help reveal changes in the Earth’s carbon storage system, both past and present. His recent research suggests that a shift in ocean microbial communities driven by a warming world could potentially make the pump more efficient in some ocean regions that may be most affected by planetary warming. These changes could in part offset larger negative effects elsewhere, one piece of positive news in a sea of uncertainty. “I take a granular view, but the findings could have huge implications,” McCarthy said.

Carbon lockup

To understand the pump’s inner workings, it helps to look at the whole machine. The great majority of the carbon in the ocean exists simply as dissolved carbon dioxide gas taken from the atmosphere. This removal process has picked up in recent years. “The massive amount of carbon that we’re putting into the atmosphere is driving sustained carbon intakes,” said Andrea Fassbender, UCSC assistant adjunct professor of ocean sciences and marine geobiochemist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing.

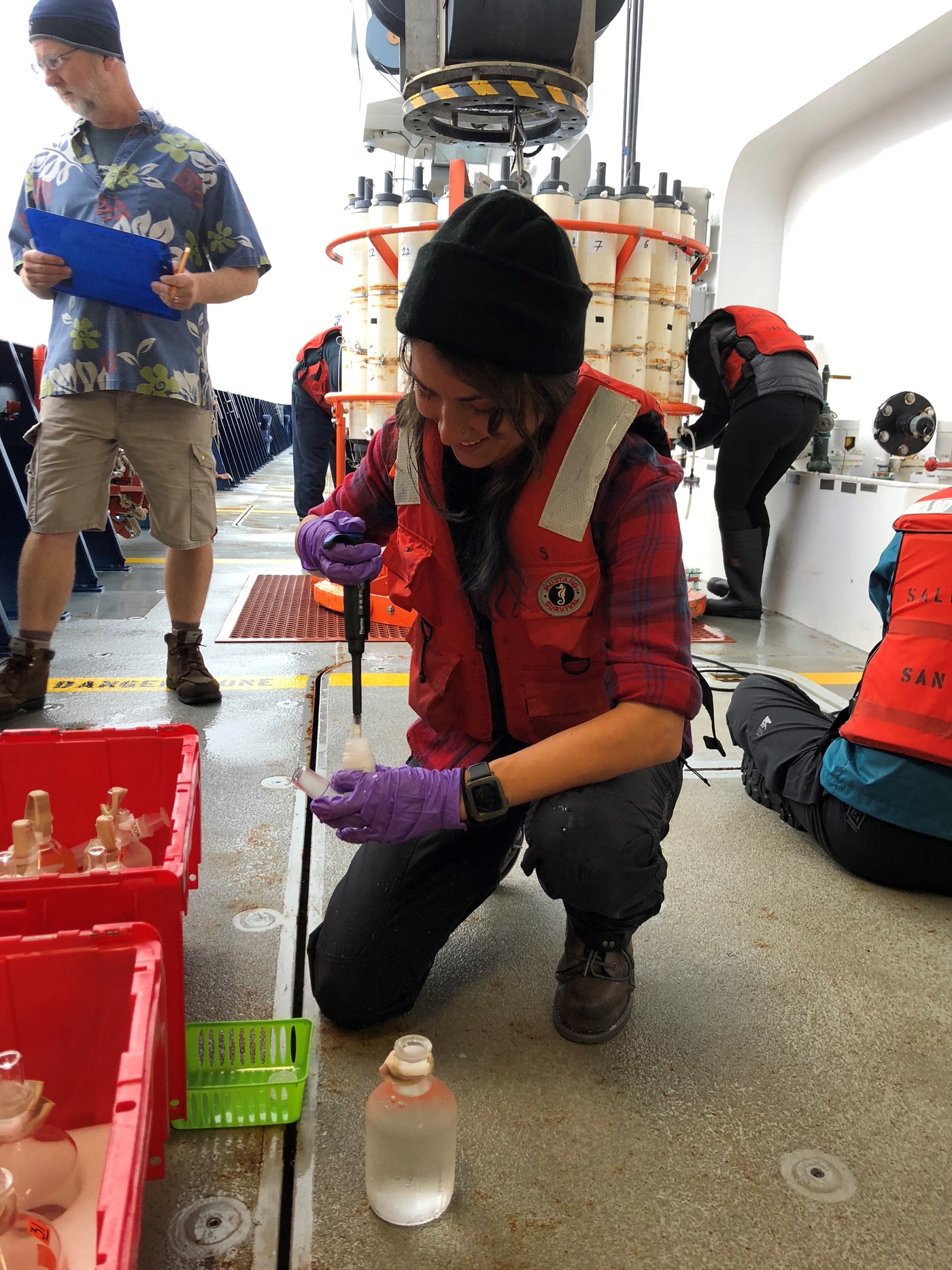

The pump gains power when carbon enters the biological arena. Algae and photosynthetic bacteria take up the element to form particles of organic matter. Over time, some fraction of those particles sinks far enough below the surface to essentially seal the carbon away from the atmosphere for centuries. Remnants of algae and bacteria also break apart in the water, leaving behind residues of carbon-rich, dissolved organic matter that similarly can linger in the water for even longer, trapping carbon over millennia. Overall, sinking particles account for about 80 percent of the carbon pumped into long-term storage by marine organisms, and dissolved organic matter accounts for about 20 percent, Fassbender said.

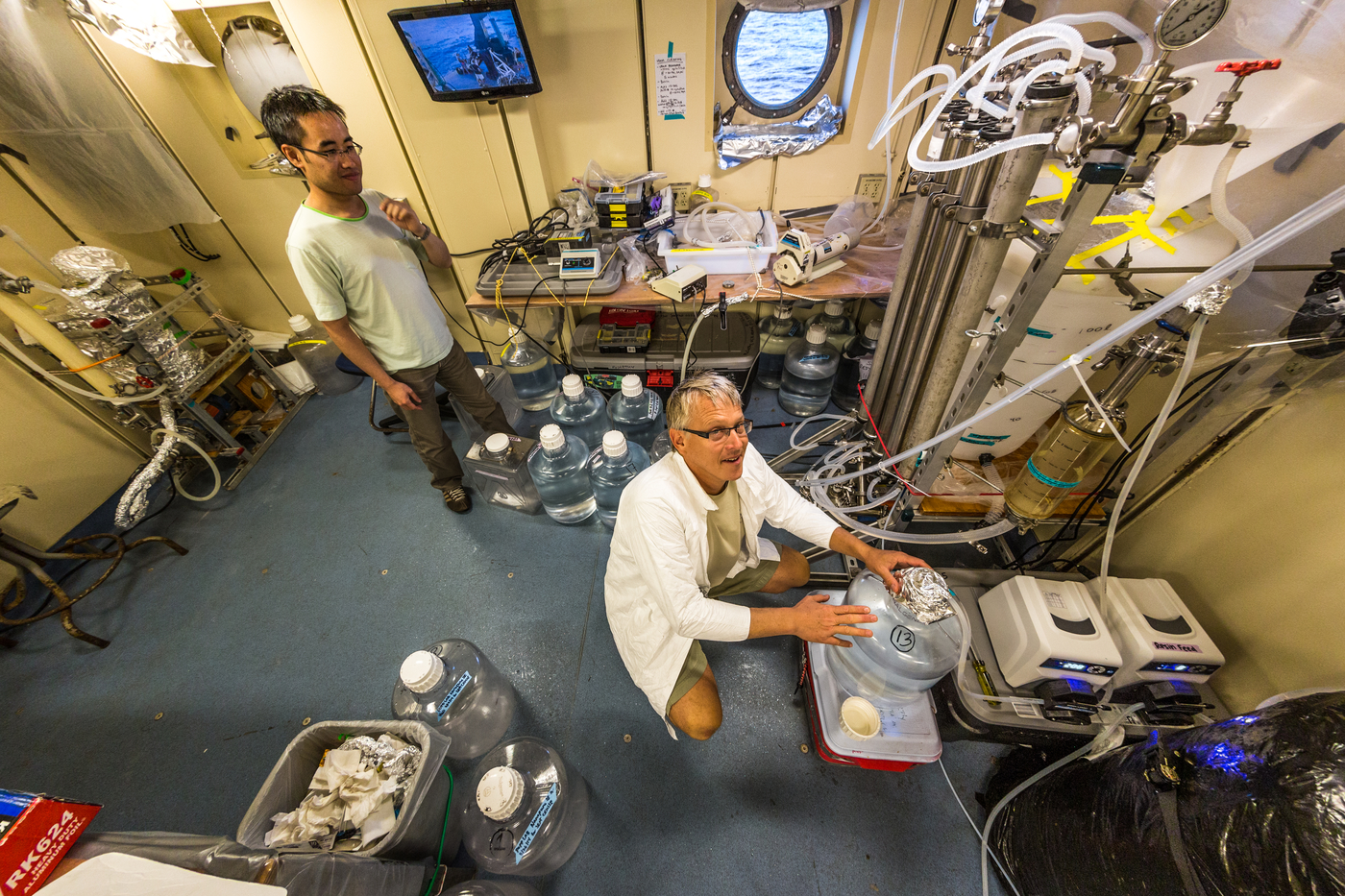

Because the pump is primarily a biological process, it runs on the basic fuel for life: energy and nutrients. It’s the nutrient flow that has sparked the attention of McCarthy and others. For more than a decade, he has been studying the life history of carbon and nitrogen in the ocean. These elements have naturally occurring isotopes, atoms with different numbers of neutrons but the same number of protons. Over the years, he and other scientists have shown that isotope ratios—like an atomic fingerprint—can help identify the sources, fates, and transformations of different forms of carbon. For example, the isotope ratios of individual amino acids from algae differ from those of amino acids from bacteria.

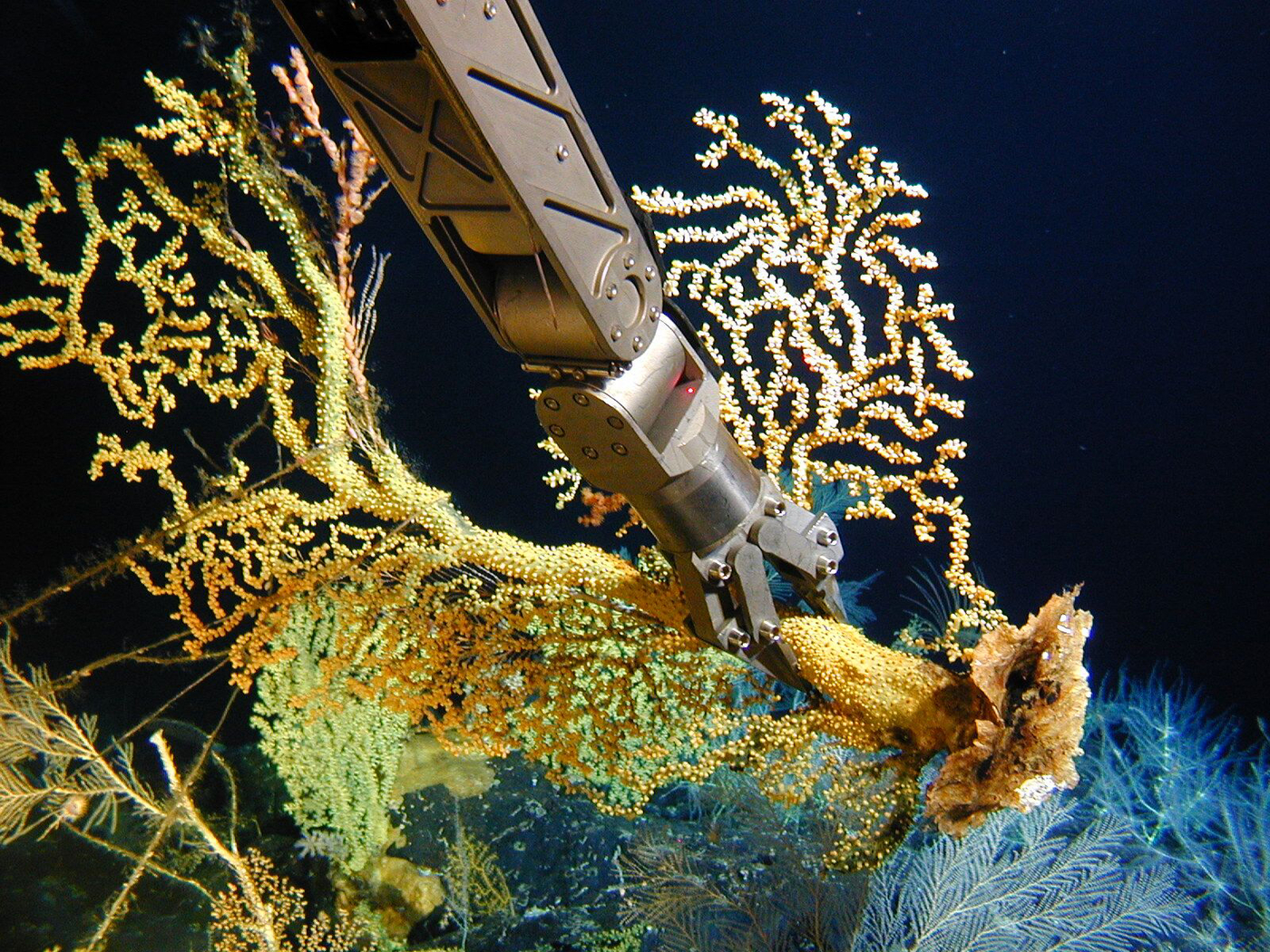

Those fingerprints can tell remarkable stories about the inner workings of the biological pump. Consider the subtropical waters off the coast of Hawaii, where McCarthy and his team gathered samples from long-lived corals some 200 meters below the surface. As reported in the journal Science in 2015, almost all of the carbon that reached the corals a thousand years ago came from one group of photosynthetic bacteria, known as cyanobacteria. However, as waters cooled during the so-called “Little Ice Age” between 1300 and 1850, very different green algae flourished, providing nearly half of the deep sea carbon flux recorded by corals below.

In the ocean and elsewhere, the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s marked the start of another major change towards warming. Around that time, the coral record shows that the biological pump shifted again away from green algae and instead became dominated by yet another type of cyanobacteria. Even though the water no longer teemed with the green algae of the past, the cyanobacteria kept the pump running. If corals 200 meters deep were eating it, that carbon clearly made it to the end of the pump, shifting our basic idea of how the pump can work, McCarthy said. “It had always been assumed that those bacterial cells don’t really sink.”

Hawaiian model

Hawaii could be a model for the Earth’s future. Its surface waters are clear today largely because the warm, sunlit layers where algae might thrive don’t readily mix with colder, denser, relatively nutrient-rich water below. As oceans everywhere warm, the assumption—and the worry—is that more parts of the ocean will become just as stratified, significantly slowing down algal growth and potentially putting a major damper on the pump. But the cyanobacteria around Hawaii suggest that pump can still work in a warming world. “Those waters aren’t an ecological desert,” McCarthy said.

McCarthy and others are also taking a closer look at the dissolved organic carbon that permeates the ocean. Dissolved carbon doesn’t sink as particles of algae or bacteria do, but rather mixes slowly into the deep ocean, taking much longer to reach depths that can effectively seal the carbon from the atmosphere. Still, its sheer volume makes it a major player in the pump, said Craig Carlson, professor of microbial oceanography, ecology, evolution, and marine biology at UC Santa Barbara. Although only accounting for about 20 percent of the annual global export via the biological carbon pump, the inventory of dissolved organic matter carbon pool is huge, some 200 times larger than the organic particle pool, Carlson said. “Tracking organic matter in the dissolved phase could be very important for understanding carbon storage.”

In recent years, McCarthy and colleagues have trained their isotope techniques on another, more recently recognized pump that can lock carbon away for hundreds or thousands of years: the microbial carbon pump. Through processes that still aren’t entirely clear, bacteria can break down molecules of dissolved organic carbon into smaller chunks that can’t be used by other microbes. Because it drifts around untouched, this inedible or “refractory” carbon doesn’t cycle through the food chain and can linger in the ocean depths for millennia.

Through various measurements and methods, including carbon dating to estimate the age of the refractory organic matter, McCarthy and others have found that the microbial carbon pump runs throughout the ocean, from the surface to the depths. In a 2016 paper in Nature Geoscience, McCarthy and his team estimated that bacteria in the deep ocean produce up to 140 million metric tons of dissolved, inedible carbon every year, an impressive feat. McCarthy suspects that the microbial pump works especially well in warm, stratified seas where microbes are both primary producers and consumers of organic matter. In theory, this pump could also therefore gain strength as ocean temperatures increase, potentially putting more carbon into long-term storage.

Carlson said it’s still far too early to answer the biggest question: will these oceanic pumps become more or less efficient in our increasingly warming, carbon-rich world? The answer depends on the complex interactions of many variables, including the productivity of algae, the effects of acidification caused by dissolved carbon dioxide, and the never-ending work of microbes.

But the urgency of the question isn’t in doubt. Stronger pumps could lock away more carbon and potentially slow climate change, but weaker ones could set off a feedback loop where the ocean takes in less and less carbon as humans continue to release more and more to the atmosphere. Whatever happens, McCarthy and others will be watching closely, down to the atoms. With so much at stake, no detail is too small.