Built from scratch

Improving vaccines with molecular insights

Vaccines are one of history’s most important medical advances, shielding large swaths of humanity from more than a dozen diseases. Worldwide, experts estimate that measles vaccinations alone have saved more than 17 million lives since the year 2000. In the United States, as a National Academies report put it in 2003, vaccines are a major reason that “death in childhood is no longer expected.”

And yet, most vaccines are still made with the same basic approach Edward Jenner used for smallpox back in the 1790s: borrowing from nature. Later scientists and clinicians improved on Jenner, to be sure, but their work remained “empirical”—based on observation rather than a coherent theory.

“They didn’t have to understand what a virus was or what an immune system was,” said Bruce Gellin, vaccine expert and president of global immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute, a research and advocacy nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. Now, however, vaccinology is in the middle of a fundamental shift. “Insights from our investments in basic science have led to leaps in technology that allow you to do things in a totally different way,” Gellin said.

One of the scientists making those leaps is Rebecca DuBois, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz. She is a rising talent in “rational” vaccine design, so called because it is based on an understanding of why vaccines work at the molecular level. Instead of borrowing from nature, her approach is to build vaccines from scratch. The aim? In addition to improving on existing vaccines, it’s to develop first-time vaccines for viruses (and other disease agents) that have so far defied vaccination efforts. That includes viruses like HIV, but DuBois’s work focuses on more common but less notorious bugs, like respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). “Traditional ways of making a vaccine have in some cases just epically failed,” said DuBois. “So, we’re taking a new approach.”

Centuries old

The current approach is old indeed, and in some ways not terribly scientific. The earliest recorded version of vaccination—in 16th century China—is called variolation. It involved grinding up smallpox scabs and either blowing them up a person’s nose or injecting them under their skin. This proved fatal in about one in a hundred people, but that was much better than the 30 percent rate of death from natural infections, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

True vaccination was first attempted in 1796 by Jenner. At the time, it was widely believed that people who regularly milked cows were immune to smallpox because they had been exposed to cowpox. Jenner, a surgeon then working in Gloucestershire, England, took material from cowpox lesions and inoculated an 8-year-old boy. In a test that would give modern ethicists the vapors, he exposed that boy to fresh smallpox a few months later, thankfully with no ill effects. His initial paper about this episode was rejected, but after more rigorous work by Jenner and others, the practice became widespread in Europe by 1800. Jenner dubbed it “vaccination,” from “vacca,” the Latin word for cow.

About 90 years later, Louis Pasteur developed a more scalable way to protect people from viruses. Instead of finding a similar but less dangerous virus like cowpox, he used the actual disease agent he wanted to combat, rabies. He rendered it harmless by exposing it to dry air. Then, in another sketchy but successful test, he used an untested formulation to inoculate two boys who had been bitten by rabid dogs. Fortunately, neither developed rabies, a routinely fatal disease.

The professionalism and safety of vaccine development have improved dramatically. But the underlying technology? Not so much. Most vaccines now in use were made by doing what Pasteur did: killing or weakening viruses and showing them to the immune system, like a wanted poster: “Look out for these guys!”

Molecular locksmithing

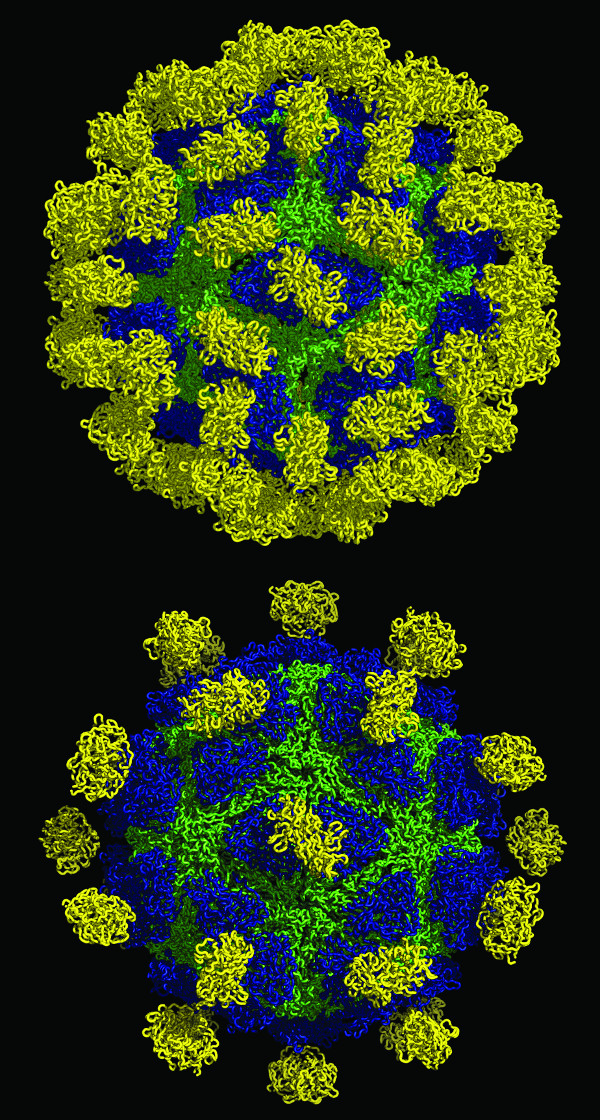

Vaccination works because the immune system can recognize invaders years or decades after being exposed to them. The human body has a cadre of “memory” cells patrolling the bloodstream. Their job is to recognize an invader, then rapidly produce proteins called antibodies to catch and neutralize it, usually with the help of a goon squad of killer immune cells. Antibodies stick only to one remembered feature on the surface of a specific invader, like a key fits a lock, and then wave a flag to bring in the killer cells.

Conventional vaccines expose the immune system to a whole virus, which can have several surface proteins. And each of those proteins can have several spots where antibodies can stick. This is like giving the immune system a bunch of locks and saying, “here, make keys for these in case you need them.” Rational vaccine design tries to find a single lock that will produce the right key—an antibody that not only sticks but protects. “We’re trying to help the immune system focus,” DuBois said.

It has already started to work. A few vaccines made with a basic version of rational design are now in use, including Flublock® for influenza and Gardasil® for human papillomavirus (HPV). However, early efforts at rational design have also put a lot of focus on HIV, said Phil Berman, UC Santa Cruz professor emeritus of biomolecular engineering. Berman helped lead the effort to develop the first HIV vaccine to enter large-scale human trials. The vaccine was not protective enough to win approval, but the trials produced valuable information, and the Berman lab is now using structure-based vaccine design to develop an improved HIV vaccine. Still, it’s a challenging disease for the relatively new approach. “HIV is the most difficult virus on the planet to work with, whereas there are a lot of other viruses that are very important for human health that this approach should benefit,” Berman said. “Rebecca’s really adding to our understanding of structure-based vaccine design and is filling in a lot of the gaps that have been left by jumping right to HIV.”

DuBois’s work focuses on viruses that mainly infect children, like RSV, and that have no approved vaccines. Her particular method of rational design is called “reverse vaccinology.” Instead of trying to generate a healthy immune response with a vaccine, she aims to build a vaccine based on a healthy immune response. She said the approach asks, what does the immune system look like in people that either don’t get infected or have mild disease?

In one prominent example of this approach, HIV researchers have studied the 25 percent of patients who generate “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” antibodies that attack many strains of the notoriously fast-mutating virus. Although these antibodies do not fully protect the patients who generate them, studying them has led to vaccine candidates that might prompt stronger immune responses. A few are now in early clinical trials.

Collaboration and cat whiskers

For her work with RSV, DuBois has partnered with drug developer Trellis Bioscience of Redwood City. The company discovered an antibody that binds the G protein on the surface of RSV. Most attempts to create an RSV vaccine have targeted the F protein, the other main component of the virus’s coat. So far, they have all failed, including ResVax, a vaccine candidate that in March proved ineffective in protecting infants when given to their mothers during pregnancy. Colleagues said DuBois’s choice to study the G protein is typical, showing how she can be tenacious but also creative.

“She has taken on incredible challenges and difficult problems, and she has nailed it,” said Tuli Mukhopadhyay, a fellow virologist and associate professor of biology at Indiana University. “She has figured out things that other people have overlooked.”

For example, DuBois was trying to catch antibodies in the act of binding to astrovirus, which, like RSV, is a common childhood infection. She tracked down a Spanish researcher at the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Alicia Sánchez-Fauquier, who had created a mouse in the 1990s that produced antibodies to the virus. The mouse’s cells had been lost in a freezer failure, but Sánchez-Fauquier had managed to save a small amount of antibody.

“She said, ‘I’m about to retire, so this is perfect. I’ll empty my freezer and give you everything I have,’” DuBois said. In an unusual maneuver, DuBois used an x-ray image to deduce the sequence of building blocks, known as amino acids, that make up part of the antibody. She then programmed a bacterial cell to produce a miniature version of the antibody. It functioned like the real thing, allowing DuBois and her collaborators to make several discoveries about astrovirus. For example, they found that, in all cases, the antibodies stick to a much larger part of the virus’s coat than anyone anticipated. This observation explains why previous attempts to develop a vaccine using smaller pieces of the coat did not work. It could, in addition, help design a more effective approach.

“I feel like nothing ever deters her. She’s like, ‘Okay, we have a roadblock. Let’s think about this logically,’” Mukhopadhyay said. That attitude paid off again with RSV. DuBois heard about the new Trellis G protein antibody and decided to just ask for it. “Basically, I emailed Trellis and asked, ‘Hey, can I study your antibody?’ They were a little hesitant, but they said sure.”

“It’s been a very fruitful collaboration,” said Larry Kauvar, Trellis founder and chief scientific officer. “She’s interested in learning about not just how to do science, but how to do science that would be useful from a commercial point of view.”

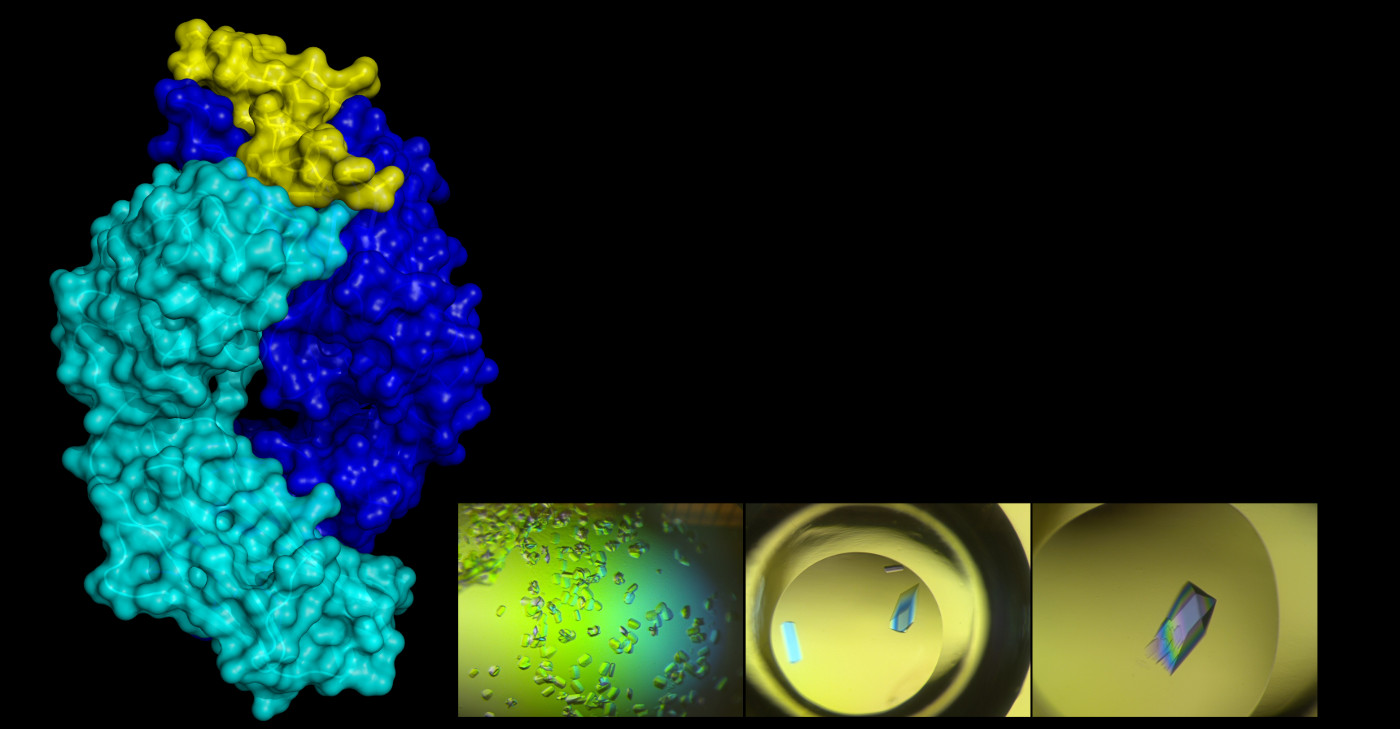

Once DuBois had the antibody, she wanted to study how it attacked RSV, trying to find the lock on the G protein where the antibody key fits. This requires inducing the proteins to form crystals, which can be shot with x-rays to produce clear images, a method called x-ray crystallography. It’s an exacting technique. Researchers first must manufacture the protein using bacteria, separate it from other proteins through an elaborate electro-chemical filtering process, and then find the recipe for a solution that crystallizes it in just the right way. Sometimes it takes 500 different formulations to find one that works, DuBois said.

The final step may be the most maddening: pulling a single microscopic crystal out of the solution. DuBois’s strategy for that involves cat whiskers, which, for some reason, work better than just about anything else. Something about them is just right for grabbing a protein crystal, she said, dragging it away from the rest, and then releasing it onto a plate of glass. The cat whiskers aren’t purchased at a scientific supply company, which adds a bit more meaning to the phrase, “built from scratch.” “My cat, Zuzu, a fluffy calico who is quite annoying and meows a lot, occasionally sheds whiskers,” DuBois said. “I always save them and bring them to the lab.”

A larger toolbox

The hard, meticulous work paid off in March 2018, when DuBois, graduate student Stanislav Fedechkin, Kauvar, and coauthors, published their work describing how the antibody attacks RSV in the prestigious journal Science Immunology. Trellis, for its part, plans to start clinical trials of its anti-G protein antibody treatment in the next year or so. If proven safe and effective, it would be given directly to infants who come to the emergency room with RSV. This is a potential improvement over the only current product for RSV, which is given preventively to high-risk premature babies. Success would also be a promising sign for a vaccine targeting the G protein.

But that vaccine is not yet in hand. It can’t be made from the G protein alone, because that protein is known to weaken the body’s immune response, which would make it unsafe in its current form. To get around this problem, DuBois and her colleagues must mutate the protein to eliminate the unwanted effects and save the good ones. There are lots of potential routes to achieve this. Perhaps a short, harmless fragment of the protein would be enough to key the immune system, or maybe a computer simulation will reveal a tweak that does the job.

By trying out options like these, DuBois and her colleagues are building a much larger toolbox for vaccine development. Gellin, of the Sabin Vaccine Institute, said the grand hope for rational vaccine design is to make people immune to the sneakiest and nastiest of viruses, as well as bacterial and other diseases that have so far eluded vaccine makers. “At the top of the list are HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and a universal influenza vaccine,” he said. “Those are the ones where these new techniques can be most helpful.”

If the RSV efforts of DuBois and her collaborators pan out (see sidebar), the first step may be to vaccinate pregnant women to protect their babies. The duration of protection is likely to be short, Kauvar said, but even if it lasts only a few months, it would cover much of the period when the risk of severe illness is highest.

Rational design could also help reduce the impacts of other viruses for which there currently is no vaccine, like astrovirus. Americans mostly experience astrovirus as a mild nuisance, DuBois said. “It’s different in developing countries. The infections last longer, there’s no clean water, and children develop co-infections. Ultimately, it can send them to the hospital and affect their growth.”

Indeed, many poorer countries have not received the full benefits of vaccination, and DuBois said she is driven partly by the desire to help children in such places. With that inspiration—and with luck, funding, and tenacity—a loftier goal may be in sight. If vaccines can reach more people and fight more diseases, perhaps everyone, not just the fortunate, will eventually be able to say that “death in childhood is no longer expected.”