BRIEF inquiries

Digital Art New Media

The nature of eco-art

Walk past the beds of succulents and aromatic flowers at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum and Botanic Garden and there sit three geodesic domes. Inside each, native plants grow in climatic conditions forecast for the near future. One is drier than the California Coast today, another is wetter, and one contains plants watered intermittently. UCSC ecologists closely monitor the plants to study how native species will respond to drastic climate change. However, scientists did not initiate this project—it sprung from the imagination of ecological artists.

The Future Garden for the Central Coast of California is one of the dozens of art installations created by world-renowned ecological artists Newton Harrison and his late wife Helen Mayer Harrison, professors emeriti in the UCSC Arts Division. What constitutes “eco-art” eludes precise definition, but to Newton Harrison, it’s art that inspires environmental stewardship and actively contributes to it. While the Harrisons designed Future Garden primarily to show people how unbridled climate change could diminish the natural biodiversity of California’s coast, it also serves as an experiment with a valuable scientific purpose: knowing which native plants can endure will help maintain important ecosystems as global temperatures increase.

“It’s the nature of artists to select subject matter they feel attuned to,” said Harrison. “We’re destabilizing all our natural systems, and it’s affecting everyone. Artists should be taking this on as subject matter.”

—Annie Roth

Earth AND Planetary Sciences

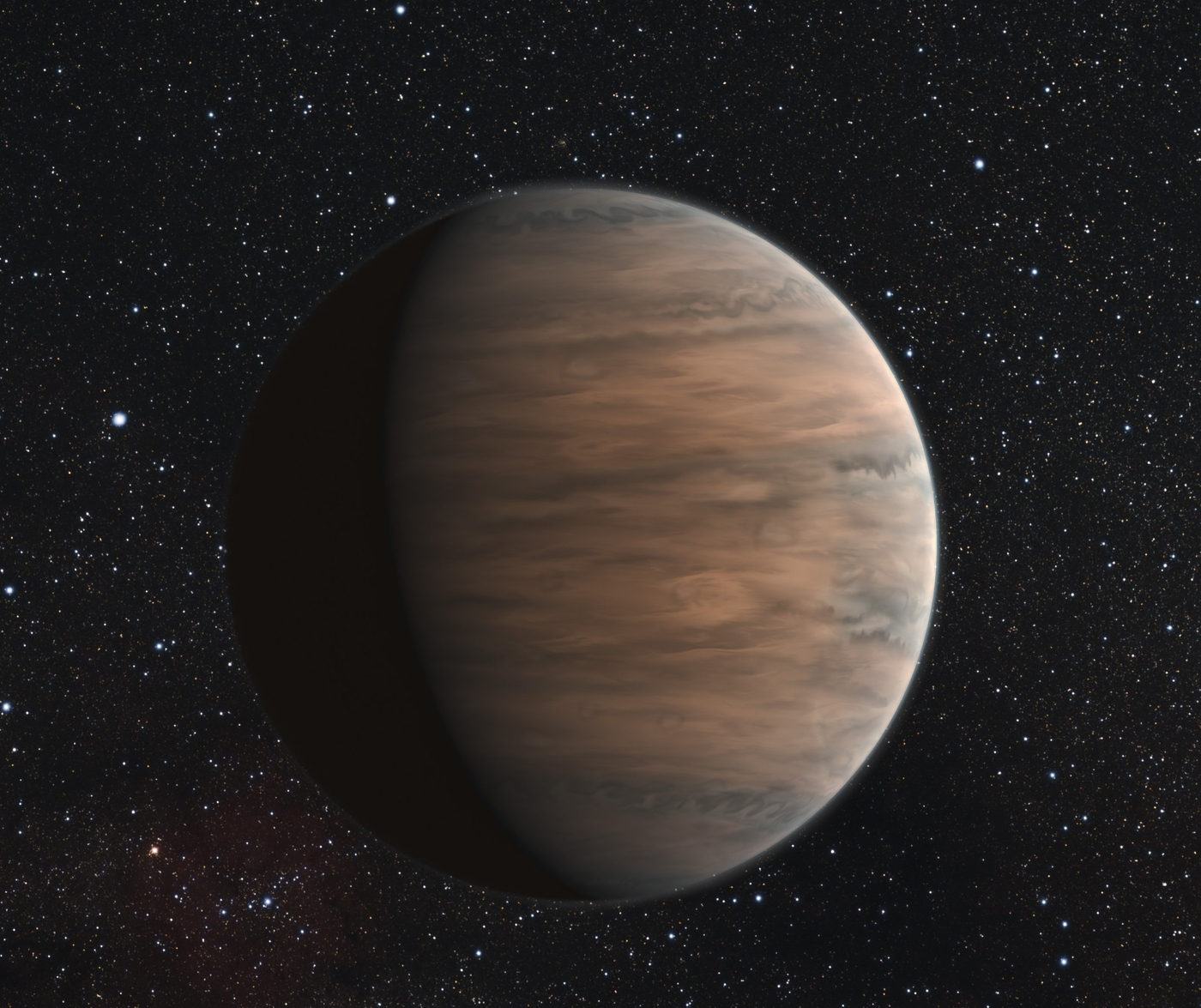

Forecasting alien clouds

Xi Zhang always has his head in the clouds…of other planets. The assistant professor of planetary sciences has built a powerful computer model that can simulate how individual molecules in a planet’s atmosphere coalesce and grow into billowing clouds.

Far from fluff, planetary clouds can provide insights into how planets form and evolve, Zhang said. In addition, understanding clouds on exoplanets could also be crucial to detecting alien life, outed by tell-tale atmospheric chemical signs.

That has not happened yet. In the meantime, however, the model has proved useful in helping to explain a puzzle involving “hot Jupiters.” While some of these close-to-their-stars, Jupiter-sized planets show a strong chemical signature for the presence of sodium, others mysteriously show much weaker signals. For the latter, Zhang’s research suggests that a thick haze is likely obscuring the view.

More recently, the model has helped explain why some brown dwarfs, despite their name, appear so red. These balls of gas aren’t massive enough to ignite and become stars, but they do emit a reddish tinge. Diana Powell, one of Zhang’s graduate students, has shown that the hue comes from smaller particles high in their atmospheres, where lower temperatures cause them to glow red. This possibility eluded earlier models, which couldn’t predict the size distribution of the particles in these alien clouds.

—Marcus Woo

Theater Arts

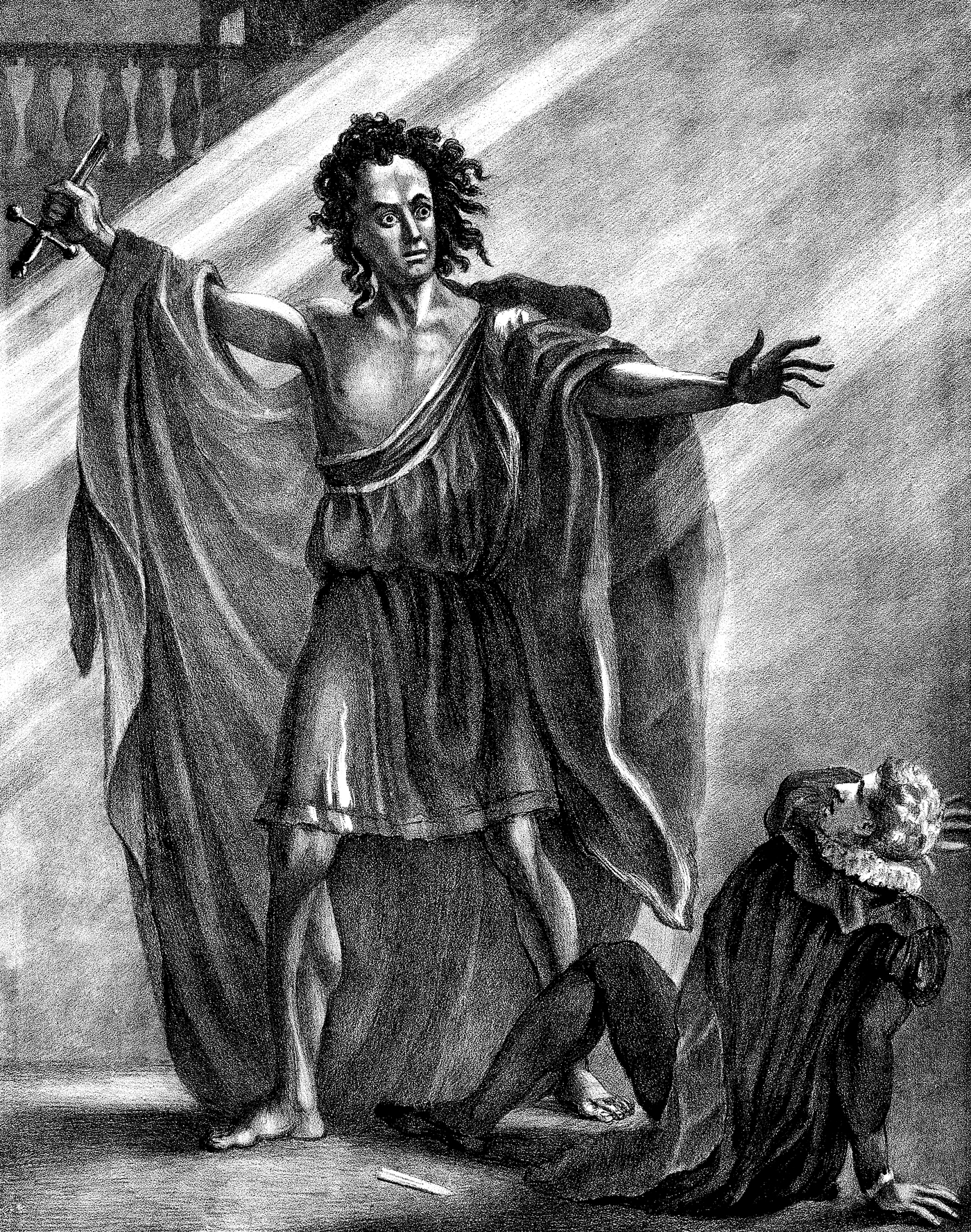

Monsters onstage

When Frankenstein’s creature lurches onstage, or Dracula disappears into the wings, what do the audience’s shudders convey? Michael Chemers, professor of dramatic literature and theater arts, sees the cultural processing of fear.

“I’m interested in freaks. I’m interested in monsters. I’m interested in deviants of all kinds,” said Chemers. He is preoccupied, he said, with how humans define and demonize the “other.”

The theater brings this question to life, literally, as actors embody society’s greatest anxieties. In his 2017 book, The Monster in Theatre History: This Thing of Darkness, Chemers explores how theater acts as a testing ground for the monstrous. For example, in her 1818 novel Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s monster turned evil only after his creator abandoned him. But by 1931, the movie monster played by Boris Karloff was an abomination from the start. Bridging the two depictions is more than a century of theatrical reinvention.

Performance art has served as a tool of monsterization throughout human history, Chemers said, including, for example, medieval European plays that demonized Jews. Today, the same tropes pop up in political rhetoric, stoking fear of immigrants and Muslims.

“Fear is very important to humans. It keeps us alive,” Chemers said. “But it also leads us into error—the more we know about fear and how it operates, the better we are prepared to move to a more just and harmonious society.”

—Stephanie Pappas

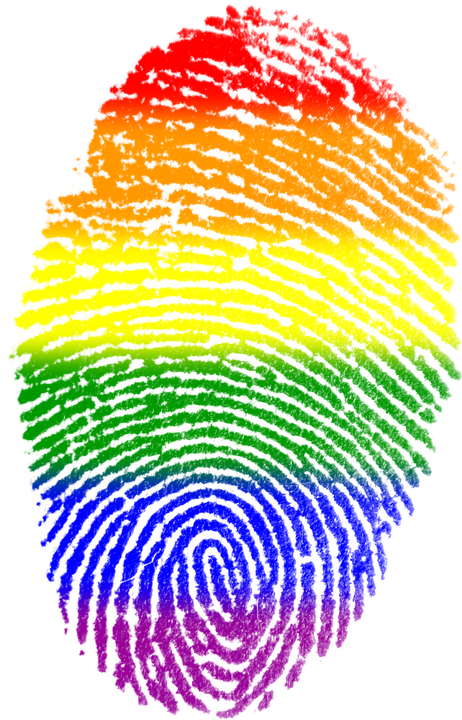

Psychology

Queer youth revolution

Unexpected results emerged from an extensive study examining the experiences of LGBT teens living in one historically supportive community (the San Francisco Bay Area), and another with historically more hostile attitudes toward sexual and gender diversity (the Central Valley).

“I was surprised by how much new identity labels are being used,” said Phillip Hammack, professor of social psychology and director of the Sexual and Gender Diversity Laboratory. “Among LGBT young people across these communities, 24 percent don’t identify as male or female, but rather as gender non-binary. That’s huge, and it’s a relatively new concept. It’s a quiet revolution.”

A person identifying as gender non-binary may blend elements of traditional masculinity and femininity or may not fall within those two categories at all.

But this revolution isn’t affecting all queer teens equally, said Hammack. Leaders within the unofficial movement were overwhelmingly teens who were assigned female at birth, but now identify as gender non-binary. And overall, there were twice as many openly transgender boys (assigned female at birth) as girls.

That doesn’t jibe with the demographic makeup of the larger LGBT community, Hammack said. So, where are the boys? Teens who were assigned male at birth but who now have a different gender identity don’t feel they can come out safely, Hammack said. “They’re worried about stigma and bullying from other boys. If they can pass as gender-conforming, they’d rather stay in the closet.”

—Sascha Zubryd

Ocean Sciences

Deep sea surveying

Mining the ocean floor is inevitable, according to associate professor of ocean sciences Phoebe Lam. Unfortunately, that could cause changes in the ocean’s dynamic metal chemistry with unanticipated consequences.

The concern centers on how miners will separate their quarry—black, potato-sized polymetallic nodules formed over thousands of years—from the surrounding sediment. The nodules contain valuable metals, including manganese, cobalt, nickel, and copper, highly prized for their use in modern electronics. Current schemes to mine the nodules involve scooping up the seabed, picking out the metal lumps on the boat, and finally pumping the dregs back below the surface. But dumping this mineral-rich sludge into the oxygenated upper ocean layer could have dire effects way beyond simply muddying the water.

Manganese oxides in the sludge, for example, bind trace metals. “Even at tiny concentrations of manganese oxides, we see a hugely disproportionate effect,” Lam said. Some trace metals are essential for life; decreasing their bioavailability could make life harder for the photosynthesizing phytoplankton that provide half of Earth’s oxygen.

In November, Lam and other researchers collected water samples from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a vast nodule hotbed. Part of the U.S. GEOTRACES GP15 cruise, a two-month expedition to survey ocean trace elements in waters from Alaska to Tahiti, the work will provide baseline measurements that predate mining. Their findings, said Lam, will help inform industry guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of harm to ocean geochemistry—and the vast web of life it supports.

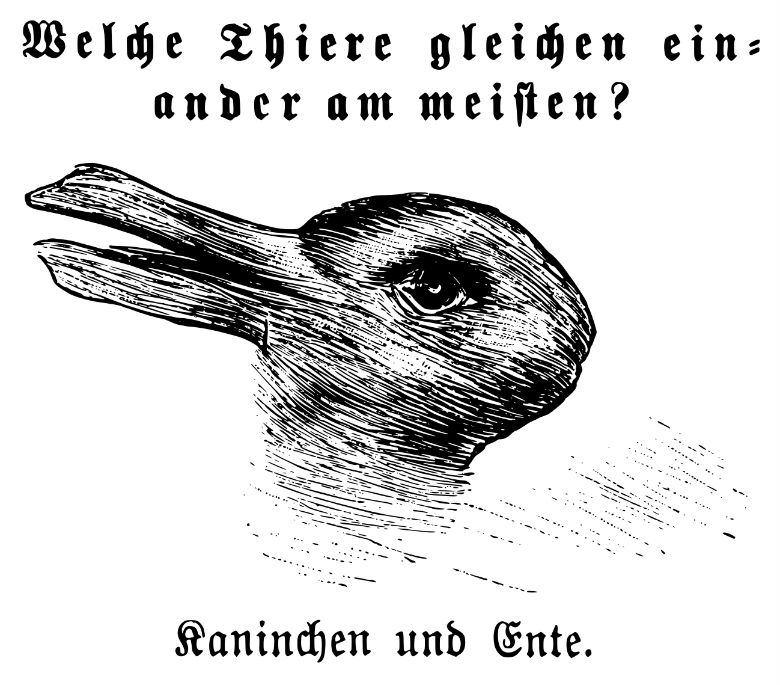

Philosophy

Seeking autism insights

There’s always been a strong link between philosophy and psychology. Studying psychological disorders has helped philosophers understand atypical ways of interacting with the world, while philosophical theories have the potential to challenge preconceptions that often limit people with these disorders. But philosophers need to do a better job of understanding these disorders, said assistant professor of philosophy Janette Dinishak, whose research focuses on autism.

Dinishak sees the autism-philosophy link as a two-way street, where philosophy should draw on the personal experience of autism in order to translate it in a meaningful way for autism researchers and the public. Dinishak explores this experience by grounding it in reports from actual autists.

Most philosophical treatments of autism center on what is purportedly missing, an emphasis Dinishak’s research suggests may be misguided. For example, one philosophical notion posits that people with autism are “aspect blind.” Coined by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, the term describes the inability to see one thing as something else. As reported in Philosophical Psychology, Dinishak’s close look at the statements of autists reveals that the concept of aspect-blindness may be far too limited to fully reflect their actual perception.

“We’re only now just starting to create a language to describe the experience of autism,” said Dinishak, who credits her mentor, Canadian philosopher Ian Hacking, with the broad ideas that shape her work.

—Stephanie Pappas

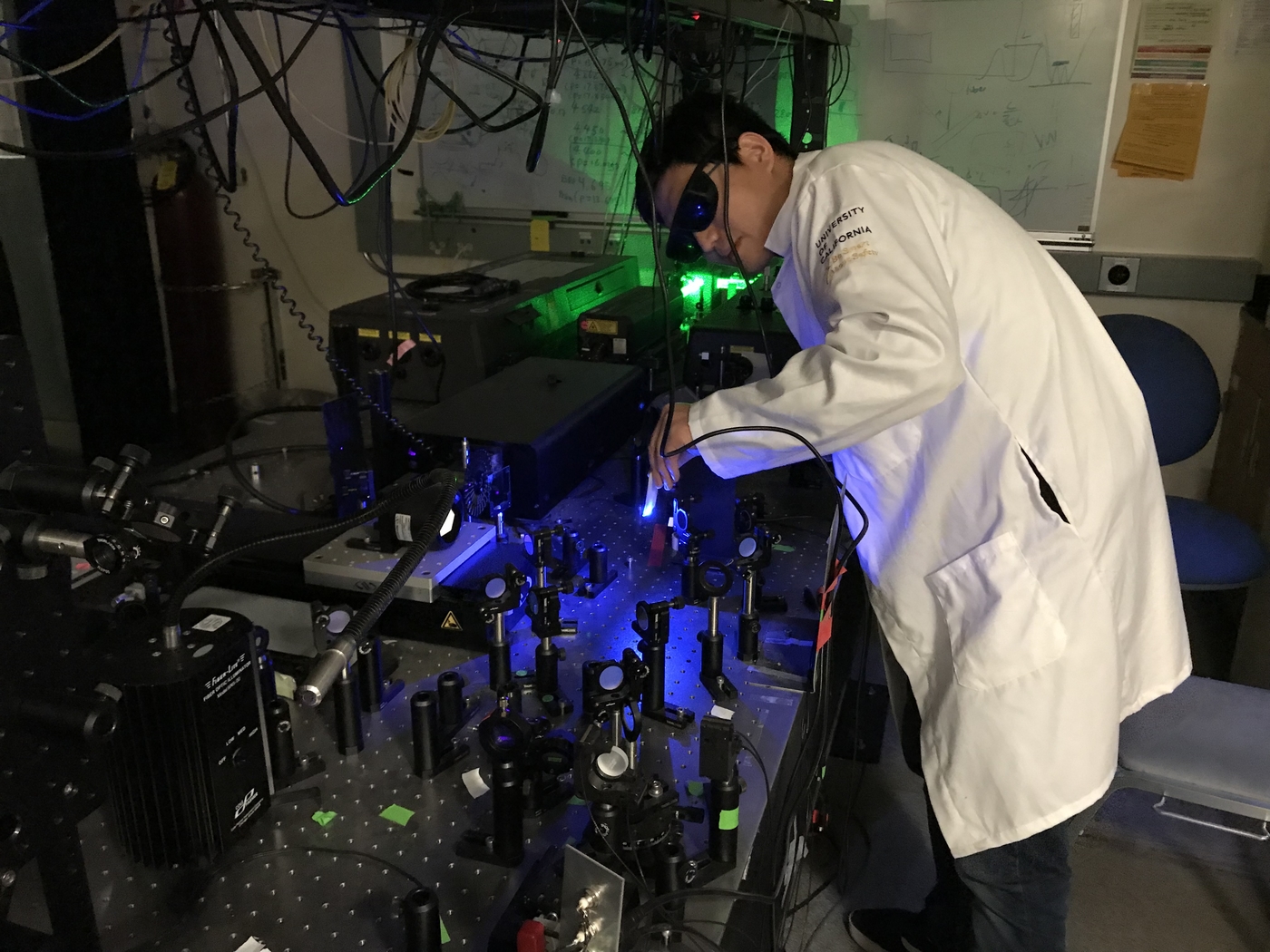

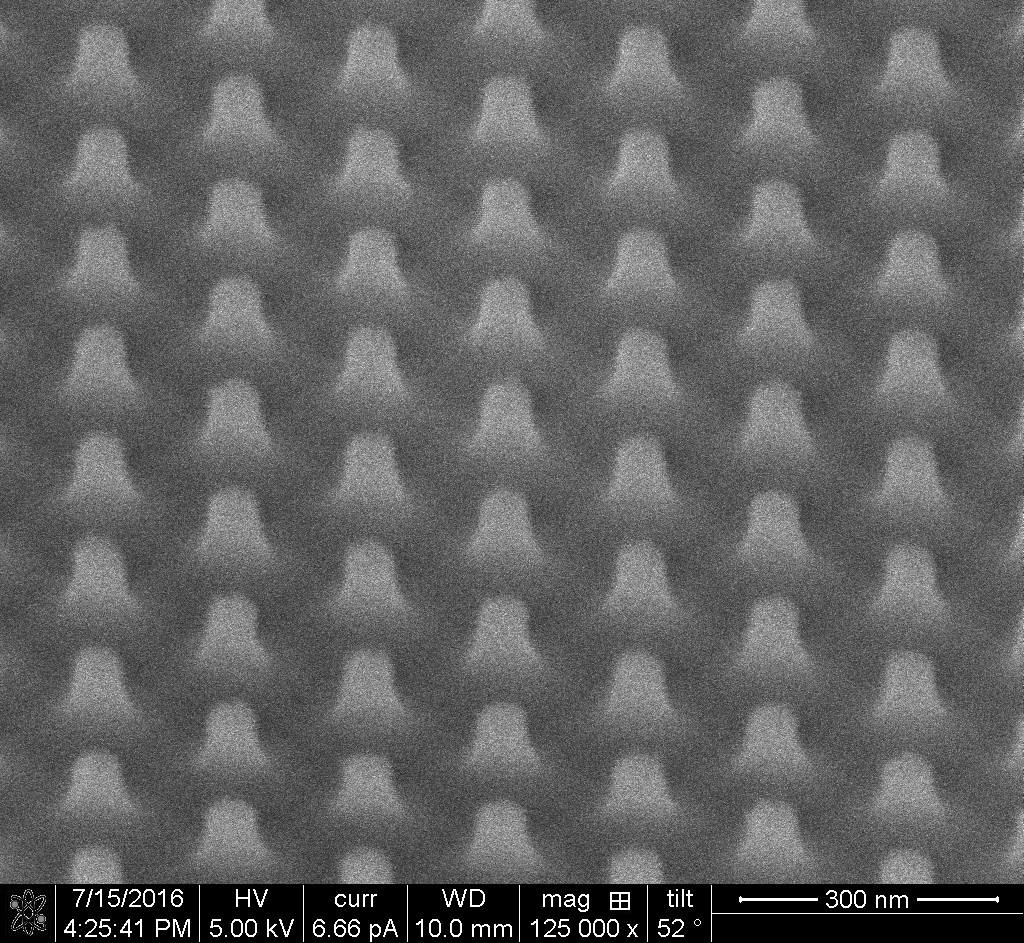

Electrical and Computer Entineering

Laser-focused memory

As computer memory devices shrink and become more powerful, more sophisticated methods are needed to assess performance and improve designs. Lasers can help measure the magnetic properties on which most of these advanced devices rely, said Holger Schmidt, a professor of electrical and computer engineering with expertise in spintronics and ultrafast optics. “With lasers we can measure things that happen really fast in things that are really small.”

For example, Schmidt is working with Samsung to study devices called STT-MRAM (spin-transfer torque magnetic random access memory). Already used in niche applications, STT-MRAM has no moving parts and at its heart contains two magnetic layers, approximately 10 nm wide and 1 nm thick (1 nm = one billionth of a meter), separated by a barrier. Within each layer, electrons act like tiny compass needles that are aligned to produce a measurable magnetization. But while the needles in the bottom layer are fixed, the top ones can rotate. Applied electric current turns the top needles, which otherwise resist rotating, and whether the top and bottom needles are aligned yields the 0’s and 1’s of computer memory.

To assess this dynamic—specifically, how much the top needles resist rotating (called magnetic damping)—Schmidt fires two laser pulses a few picoseconds apart at the magnetic material. The first spins the needles, and the second monitors their return to position, producing accurate measurements that are informing decisions about which materials to use in the next generation of memory devices.

—Marcus Woo

Sustainability Science

Focus on the coast

Coastlines are changing fast, and management practices aren’t keeping up, said Anne Kapuscinski, professor of environmental studies and director of the new Coastal Science and Policy Program. “There’s real urgency now. The harmful impacts of climate change are already being felt in coastal areas worldwide.”

Based at UCSC’s Coastal Science Campus on Monterey Bay, the two-year master’s degree program aims to help students develop innovative strategies for coastal conservation and sustainable use management. The interdisciplinary curriculum emphasizes mentorship, collaboration, and leadership training. In addition to workshops and specialized coursework designed for the program, each student will complete a major project working closely with an outside partner such as a research institution, NGO, private company, or government agency. The interests of the inaugural class include Caribbean manatee protection, climate change insurance risk analysis, Chinese aquaculture management, and local grassroots watershed management.

“The program is exceeding my expectations,” said student Mali’o Kodis. “One of the greatest achievements—and challenges—of this program is addressing the wide array of interests, backgrounds, and unique experiences within our cohort of 10 incredible young leaders.”

“They help each other but they also push each other,” said Kapuscinski, whose own research focuses on increasing the sustainability of aquaculture, the world’s fastest growing food sector. “It’s all aimed at informing policy and real action on the ground.”

—Sascha Zubryd

Computer Science

Protecting data privacy

What if your cell phone could assess your risk for developing diabetes? For that to be possible, a predictive model would first need to be trained on vast amounts of user data. And that poses a problem, said Abhradeep Guha Thakurta, assistant professor of computer science and engineering.

“Access to this type of personal data is an insanely sensitive issue,” said Thakurta. “How do we harness such data while still protecting privacy?”

Thakurta has developed machine learning algorithms, or computational rulesets, to help solve this problem. His approach is based on introducing randomness into the data. Imagine your data being sent from your phone to a company server. While your actual data might reveal a family history of heart disease, Thakurta’s algorithms could replace this truth with its opposite—you don’t. “The data are intentionally a little bad,” he said.

Feeding models slightly bad data turns out to be good for them—they learn the general trends, without relying on any individual’s “real” data. The method maximizes data utility, while also maintaining user privacy.

Several companies are working to adapt his approach to their technology, Thakurta said. Apple, for example, is already using it in all their devices to ensure keyboard stroke privacy.

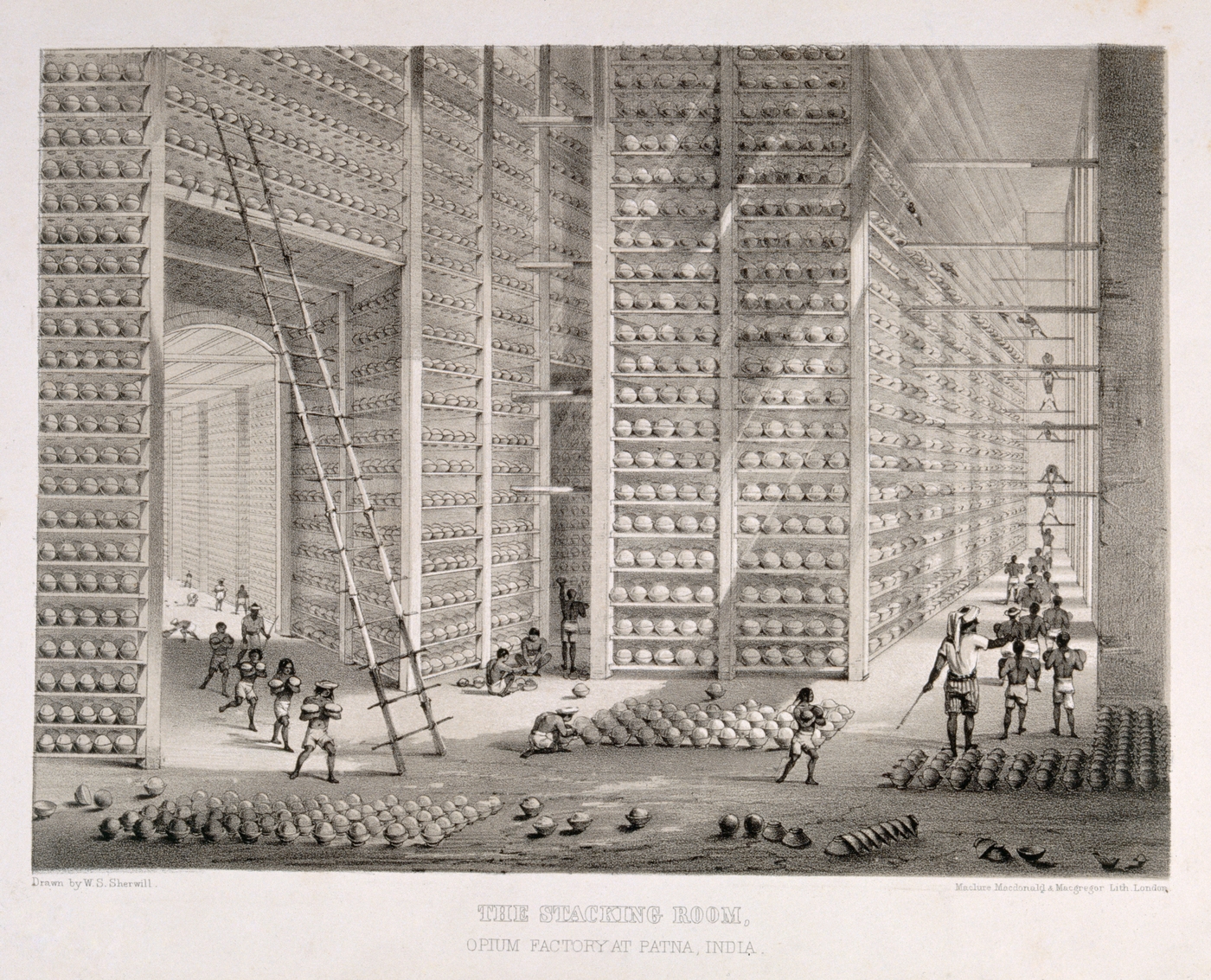

History

Opioid amnesia

It’s big news that opioid addiction in the U.S. has reached epidemic proportions. More than 48,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2017, leading the Department of Health and Human Services to declare the opioid crisis a public health emergency.

So where did this huge problem come from? One could argue it started in 1804 when German chemist Friedrich Sertürner isolated and extracted morphine from opium poppies. When morphine was first sold to the US, it was marketed as a treatment for pain and opium addiction. The irony became evident during the Civil War, when morphine addiction among the enlisted grew so widespread it became known as “soldier’s disease.”

Benjamin Breen, assistant professor of history, sees our current crisis as “a continuation of an older story” that began long before Sertürner discovered morphine. In his forthcoming book, The Age of Intoxication: Origins of the Global Drug Trade, Breen examines the origins of the global drug trade and its role in shaping modern society.

His research underscores the point that history repeats itself. “As a society, we have amnesia when it comes to these drugs,” he said. “We don’t remember the experiences of our great-grandparents’ generation. They had morphine and we have Oxycontin. The two drugs are slightly different but they’re both opioids.” And they cause the same problems.

—Annie Roth

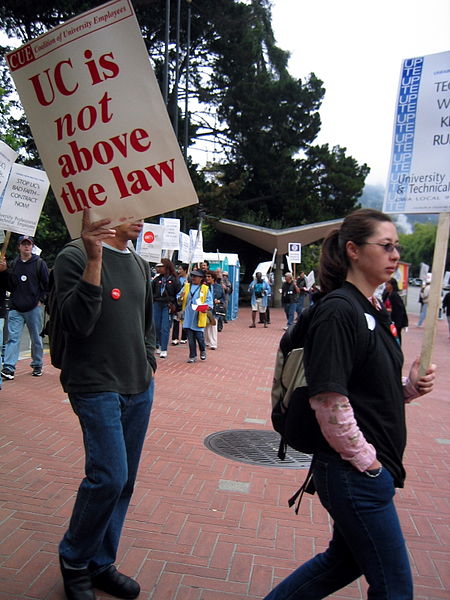

Critical race and ethnic studies

Introspective U

Supporters of secondary education often fondly reminisce about the 1960s as the golden era of the university (free in-state tuition at UC!). But Nick Mitchell, assistant professor of feminist studies and critical race and ethnic studies, seeks to put this nostalgia into a broader perspective. Universities reluctantly made concessions to feminist and minority activists during this formative time, but less for the greater good and more as a public relations strategy to promote American Cold War ideals and to maintain control over student activism, Mitchell said.

Mitchell explores how such motivations impact the university within the U.S. capitalistic system in his forthcoming book from Duke University Press, Disciplinary Matters: Black Studies, Women’s Studies, and the Neoliberal University. Universities can provide space to think outside of the market-driven box, Mitchell said, but they can also be exploitative, leaning hard on low-paid adjunct labor to teach students, for example. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis that resulted in increasing budgetary constraints for universities, Mitchell and other activist scholars in the fledgling field of Critical University Studies aim to challenge nostalgia about the past, highlight inconsistencies between the university’s public mission and actual practices, and propose policy changes to address them.

“It’s incredibly difficult to be honest about universities from within, because so many times, our ideal of what a university is conflicts with what is happening on the ground,” Mitchell said. “I felt the need to try to rebalance the scales and tell a different story.”

—By Stephanie Pappas

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Prosthetics next step

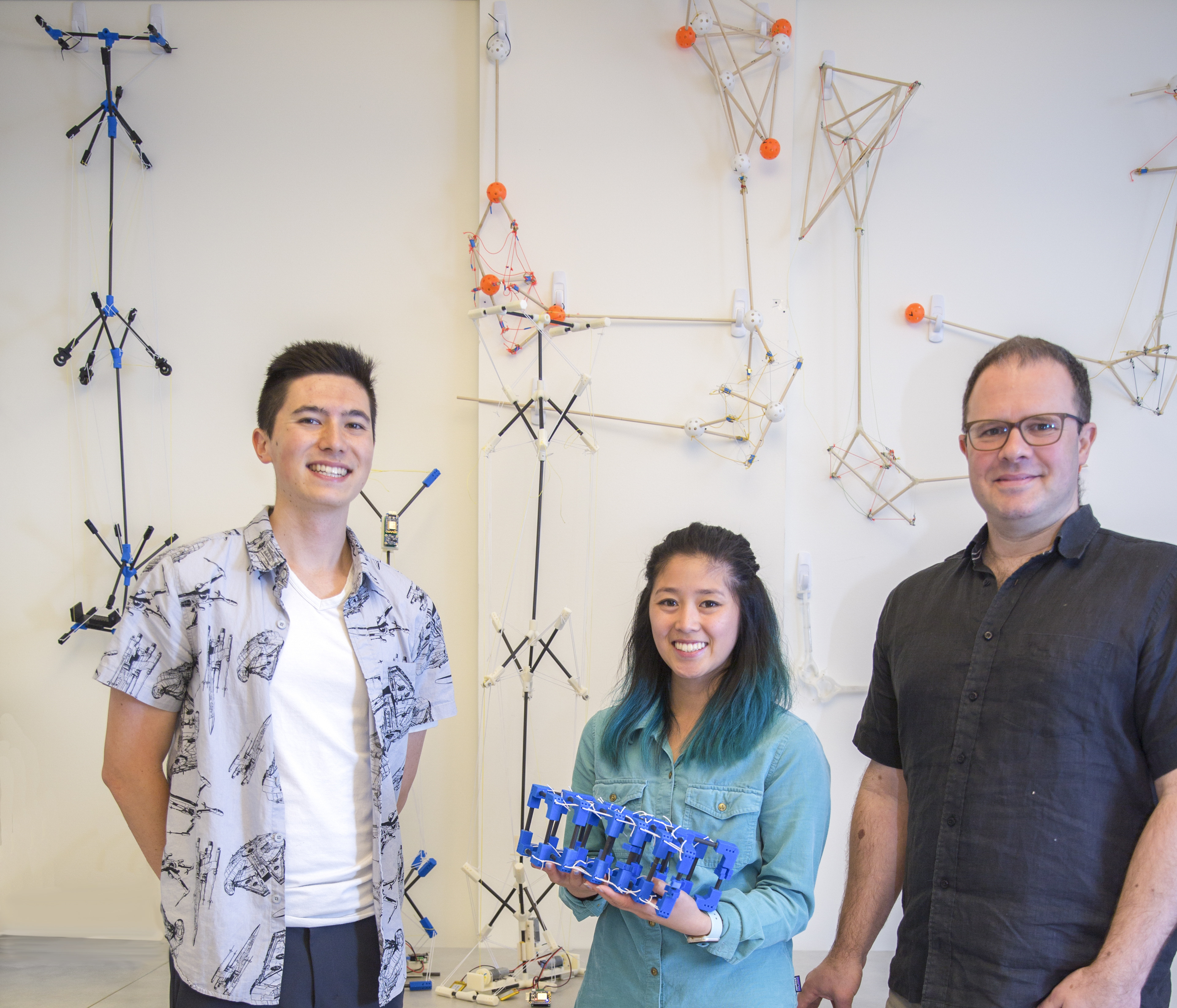

When Erik Jung toured an exoskeleton company in high school, he witnessed how the device helped a paralyzed man, shedding tears of joy, walk for the first time in 20 years. That moment inspired Jung to study how robotics can help people.

Today, he’s a graduate student in the lab of Mircea Teodorescu, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering. With graduate student Victoria Ly, they’re designing prosthetic legs that mimic the anatomical motion of the real thing, using an approach called tensegrity. In place of bones, tendons, and ligaments, the prosthetic has a balanced system of rigid rods and elastic bands, all pulling and pushing on one another, distributing forces like a real leg. Electric motors act as muscles to add extra push as needed.

“It could lead to potentially cheaper prosthetics that feel more natural to users,” said Jung. An unnatural gait, common in amputees using conventional prosthetics, can lead to pain and discomfort. Robotic exoskeletons work, but each device can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Tensegrity, Teodorescu said, doesn’t need as much electronics, which cuts the cost. The team’s working prototypes, which are still far from what someone would use, only cost about $100. The researchers are still working out basic function and control, he said, but hope to begin human testing soon.

—Marcus Woo

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Fishy behavior

It might seem unlikely that fish have much to teach us when it comes to parenting. Most don’t, and when they do, the father usually parents solo. However, as shown by the research of Suzanne Alonzo, professor of evolutionary biology, studying the reproductive habits of fish can offer insights into the evolution of our own.

Fish make useful models for this work for many reasons, Alonzo said. “When you think about reproductive systems, fish pretty much do it all.” While some change sex throughout their lifetimes, others are male and female at the same time. And while some keep it simple, just releasing eggs and sperm into the water column, others engage in complex mating rituals involving social interaction and cooperation among several individuals.

The ocellated wrasses (Symphodus ocellatus) studied by Alonzo fall into the latter, more complicated camp. Three types of males—nesting, satellite, and sneaker—compete for the favors of females, but only nesting males parent the offspring. When these fish prepare to mate, unrelated nesting and satellite males—despite being competitors themselves—will team up to keep sneaker males away from potential mates. While hard to explain from an evolutionary perspective, this blend of cooperation and competition is observed across taxa from insects all the way up to mammals, Alonzo said, adding an intriguing twist to the science of seduction.

—Annie Roth

Library

The Gonzo collection

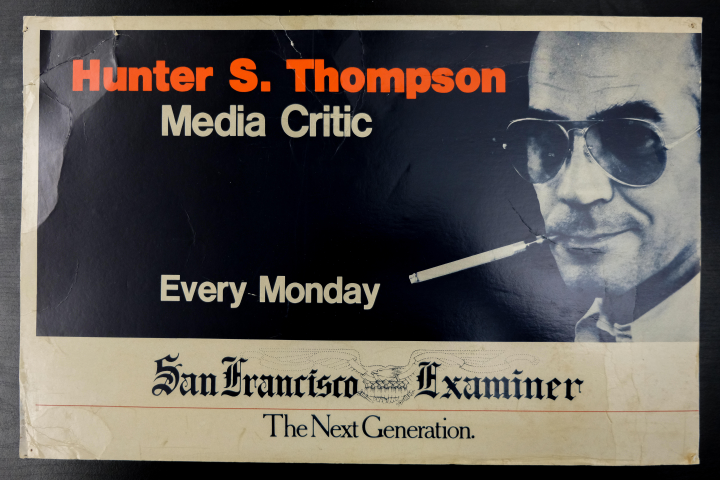

Hunter S. Thompson, counterculture icon with antiauthoritarian convictions and an affinity for drugs and firearms, has found a home at UC Santa Cruz. Thompson pioneered “Gonzo journalism,” an immersive, personal, often irreverent style, and much of his substantial body of work will soon be publicly available at the UCSC library in a newly donated, 800-volume collection.

The collection was gifted to the university by Eric C. Shoaf, author of Gonzology, a bibliography of Thompson’s works. Shoaf spent 30 years compiling the collection’s eclectic assortment of materials, which includes first editions, translations, posters, event fliers, and original-format periodicals. Its breadth makes the collection a valuable resource for literary research, including tracking Thompson’s cultural impact, said Teresa Mora, head of the library’s special collections and archives.

“Nuances between translations are important for understanding a work’s significance and getting at the author’s original intent,” she said, “and the ephemeral materials provide insight into how Thompson’s works were received at the time.”

The Thompson Collection complements the library’s Grateful Dead Archive. “We have an unofficial counterculture area, and Thompson fits very neatly with that,” Mora said.

“There’s an exquisitely printed little pamphlet of the eulogy Thompson wrote for Timothy Leary,” Mora said. Inside, there’s a sheet of blotter paper cut into stamps with Leary’s head on each. “It’s not dosed, but it conveys Leary’s impact in a unique way.”

—Sascha Zubryd

Anthropology

Mushroom magic

Matsutake, one of the most valued mushrooms in the world, make a perfect subject for thinking about how humans impact other life on Earth—for worse and for better—according to professor of anthropology Anna Tsing. The mushroom takes center stage in her 2015 book, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.

Now a global phenomenon, matsutake first found fame in ancient Japan. The mushrooms grew in satoyama, village forests where people cut trees for firewood, harvested fruits and mountain vegetables, and raked away litter to lay on their fields.

These forest management practices created a perfect environment for matsutake. Matsutake grow mainly on the roots of red pines in Japan, and the human activity encouraged the weedy red pines to flourish. Felling trees also favored deciduous oaks, which grew back from their intact roots. The oaks in turn discouraged red pine’s competitors—all the better for matsutake. Satoyama are now less common in Japan, but, thankfully for its devotees, matsutake thrives elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere.

Matsutake show us that many partners are required in the ecological dance that allows life to flourish, said Tsing. In fact, scientists have never been able to artificially cultivate matsutake. Rather, “you need a whole complex ecological community,” she said—humans included.