Agents of Hope

Tackling the Golden State’s crisis of poverty

Hermes Padilla still recalls hearing rats scamper above him in the ceiling of his $900-a-month room, once used for doing laundry in the rental house he shared with five others. “We had a slumlord,” the UC Santa Cruz student said, and she wasn’t fixing the rat problem, the leaks, the mold, or the lead paint. Eventually, Padilla left. Now couch surfing with friends, he’s trying, like many others in Santa Cruz County, to find a safe and affordable place to live.

Padilla grew up in Los Angeles County, in a family that has always rented. Like many thousands, they dealt with rent increases and rental shortages, while others crowded into houses to make rent more affordable. Those who fell through the cracks and couldn’t find a spot in the overburdened shelters ended up homeless. The City of Angels now has so many homeless people that Mayor Eric Garcetti recently declared it “the greatest moral and humanitarian crisis of our time.“

But Los Angeles and Santa Cruz counties—with some of the highest poverty rates in the state—are not alone. In fact, most Californians don’t make enough to afford the state’s high cost of living. The entire state, while boasting one of the wealthiest economies in the world, also suffers from the highest poverty rate in the country, with dire consequences for many. How did this happen? Experts point to the state’s housing and tax history, as well as to the rise of the information/technology economy.

What can be done? Answers for dealing with this seemingly intractable problem are being sought through one of UCSC’s three recently designated academic priority areas: “Justice in a Changing World.” Reflecting this major area of cross-disciplinary research at UCSC are three new studies led by UCSC faculty who examined different aspects of the wealth gap: income, affordable housing, and access to financial services. Based on their findings, they propose possible solutions to make life more equitable and dreams more achievable for those struggling in the economic shadows of huge financial success.

Shrinking incomes

Once a bucolic agricultural region called the Valley of Heart’s Delight, Silicon Valley is now famous worldwide: first, for its computer and electronics industry, now also for the internet and rise of the digital economy. The technology hub stands as a model of success admired by many who want to emulate it.

Chris Benner, UCSC professor of sociology and environmental studies and director of the Santa Cruz Institute for Social Transformation, sees it differently. As a graduate student 20 years ago, Benner published a research report on the impacts of Silicon Valley’s emerging technology economy. At the time, he said, he wanted to contribute to the national debates about what was happening due to changes in the information economy. “People were worried about the disappearance of jobs,” he said, and there were concerns about how to regulate the emerging tech industry and protect workers. When Benner began to see similar concerns surfacing again—such as those highlighted in the last presidential campaign—he approached several colleagues and community partners to follow up on his earlier findings.

Funded by the UC Berkeley Labor Center, Everett Program, and Working Partnerships USA, Benner and collaborators sifted through and analyzed reams of economic data in search of answers. The resulting report is aptly titled Still Walking the Lifelong Tightrope: Technology, Insecurity and the Future of Work.

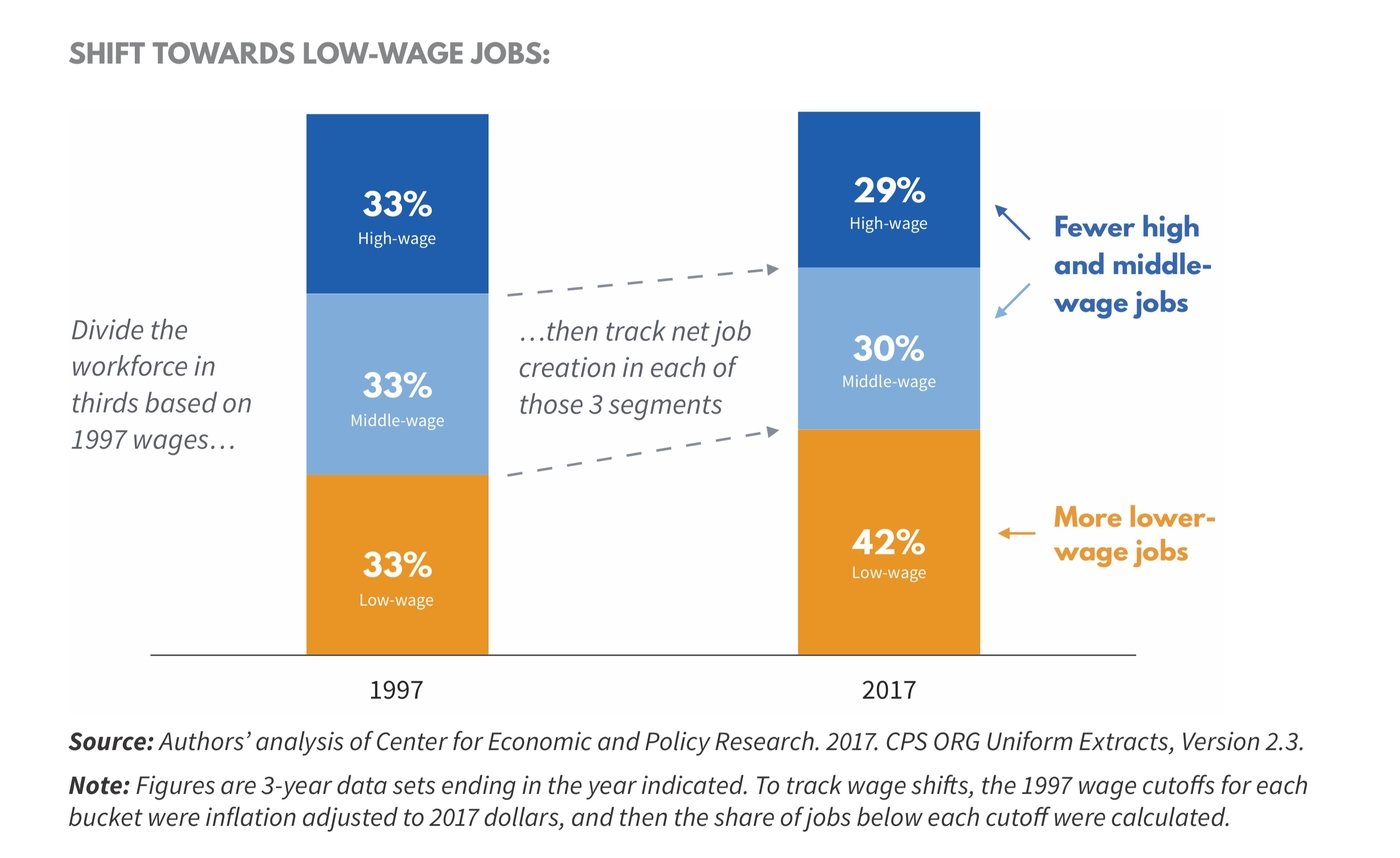

One of the biggest surprises, said Benner, was the level of wage stagnation among workers in the information/tech economy. Even though their per capita output had increased substantially, most workers weren’t seeing the rewards of their efforts. Instead, wages in the region—when adjusted for inflation—were less than what was paid 21 years ago. In fact, nearly nine out of 10 jobs in Silicon Valley paid lower wages. On top of that, the concentration of jobs had shifted from high- and middle-wage to low-wage.

“We expected to see inequality,” said Benner. But they did not expect to see how widespread it had become. The huge profits generated by industry giants such as Facebook, Apple, and Amazon, he said, are going mostly to the owners, executives, and stockholders, not to workers’ wages and operations. The business models of these companies focus on global expansion and turning small technology-related changes into big money-makers. This means, he said, there’s little or no associated expansion of local middle-class employment and minimal change in spending or investment in the local community.

Most who make the enormous revenues possible, including the communities that provide the infrastructure to support business operations, are short-changed, said Benner’s coauthor Louise Auerhahn, director of economic and workforce policy for Working Partnerships USA, which produced the related brief Innovating Inequality? “The creation of rules and incentives that promote winner-take-all markets and the pursuit of windfall profits,” she said, “are leading firms to choose business models that exclude the vast majority of people who contribute to the tech industry’s success.”

To help remedy this, the group’s report includes several recommendations, especially for changes at the local level. For instance, tech companies could commit to sharing a greater portion of their revenue and profits with workers and, through taxes, to help maintain and develop the communities that support them. In another step toward improving wage equity, businesses could guarantee at least the minimum wage and insist on high standards in working conditions for subcontractors. Finally, businesses also could partner with surrounding communities to reduce the negative impacts of tech industry growth on, among other things, housing, increased traffic, cost of living, schools, and transportation.

Some suggested changes are already underway. The city of San Jose is negotiating with Google on ways to mitigate the impacts of a proposed complex with up to 20,000 new employees. And the call to action for the relatively new coalition campaign Silicon Valley Rising is “We’re inspiring the tech industry to build an inclusive middle class.” According to campaign director Maria Noel Fernandez, “It’s incredibly important that these workers organize, especially in an area where the cost of living and risk of being priced out of your community is so high.”

Unaffordable housing

Fallout from the wealth gap in the San Francisco Bay Area and its impact on the shortage and soaring cost of housing reverberates throughout the region. In Santa Cruz County, long-time public works employee John Holguin had to move farther south to put a good roof over his family. Rentals simply were too high in Santa Cruz, he recently told the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

With the dismal lack of affordable housing construction, people are at the mercy of the rental market. And it has not been kind. “Rent eats first” was the refrain heard over and over again from the 1,900 Santa Cruz County renters recently surveyed for the UCSC No Place Like Home (NPLH) research project (see sidebar below). Residents said that they would put paying rent ahead of buying food or taking care of health-care needs, said associate professor of sociology Steve McKay, who co-led the project with sociology professor Miriam Greenberg. The work “brought home how essential housing is to general well-being.”

The research began at the request of the nonprofit community partners Community Bridges, Community Action Board, and California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), as well as the Service Employees International Union, Local 521. Together, the group designed a three-year investigation into how the affordable housing crisis affected the community, “particularly the most vulnerable and undercounted—low- and moderate-income renters.”

The study showed that more than 40 percent of renters spent over half their income on housing. Nearly 30 percent lived in overcrowded conditions. Half of the renters who moved in the last five years did so involuntarily, forced out due mostly to rent increases. Renters also told stories of living under slumlord conditions. Over and over, residents in crisis explained their troubles and seemed thankful to have someone to listen.

“In the debate about affordable housing development, the voices of those most affected are rarely heard,” said Gretchen Regenhardt, a CRLA regional directing attorney. To have UCSC step in was important, she said, “Agencies like mine that deal with the legal issues affecting low-income people operate on a shoestring and don’t often have the capacity for such a wide reach.”

Although the final report remains in progress, many of the findings were released and posted on the NPLH website (noplacelikehome.ucsc.edu) to help inform the Santa Cruz community as residents debated both a proposed renter-protection measure and an affordable housing bond on the November ballot. Project members also helped organize and present information at several forums on the affordable housing crisis, with some events drawing hundreds of participants.

Greenberg and McKay also wrote an op-ed in the local newspaper that included recommended solutions. The research, they said, made it clear that steps need to be taken to protect tenants “through rent control, just-cause eviction, and legal aid; preservation of existing affordable housing, through dedicated funds and land-use; and, over the long-term, production of new affordable housing, through reinvestment in social housing, expansion of workforce and student housing, and creation of nonmarket alternatives like limited-equity co-ops and community land trusts.”

It remains unclear, however, when change might come to Santa Cruz. The November ballot’s rent-control measure, which would have restricted evictions, limited rent increases, and created a rent board, was opposed by 62 percent of voters. The affordable housing bond similarly failed; while it was supported by 55 percent of voters, a two-thirds majority was needed for passage.

Un- and underbanked

Raisa Sanchez grew up in the rural town of Watsonville south of Santa Cruz surrounded by a family with agricultural roots. A child of immigrants, she knows firsthand the difficulties of navigating new cultures, with their different languages, skills, and traditions. She now draws on this life experience in her work helping low-income Watsonville residents as a senior program manager with the affordable housing enterprise MidPen Housing Corp. One of the most important systems to access and navigate, said Sanchez, is banking services. Otherwise, it’s tough to get out of poverty.

“The financial system in the United States and internationally depends on credit and your ability to build it,” said Maria Cadenas, executive director of the nonprofit financial services organization Santa Cruz Community Ventures (SCCV). To build wealth, “it’s important to understand credit and leverage it.” This typically means having savings and loans accounts within the traditional banking system. But low-income workers in particular don’t have them or use them infrequently, so they become the “unbanked or underbanked.”

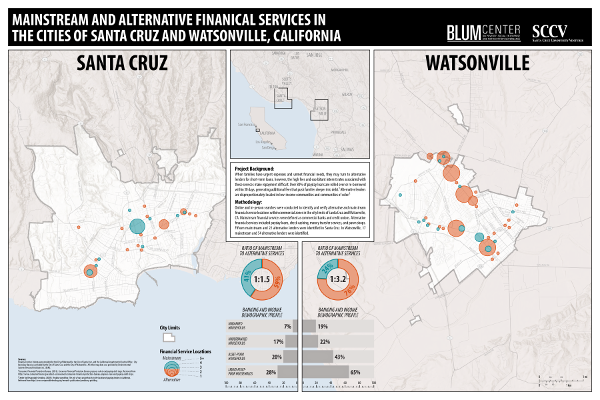

To investigate the challenges of this group, SCCV and the UC Santa Cruz Blum Center on Poverty, Social Enterprise, and Participatory Governance partnered together. “Nationally, we know that families who are unbanked and/or underbanked are especially likely to turn to alternative lenders to meet basic financial needs and that the exorbitant rates charged by these services deepens hardship. We wanted to learn more about this problem locally and what could be done to foster greater economic inclusion,” said psychology professor Heather Bullock, Blum Center director and coprincipal investigator with postdoctoral researcher and lecturer Erin Toolis.

Latinas who managed households appeared to be among those facing the greatest barriers, so the team decided to focus on them. More than 100 women in the region shared their experiences with the researchers. The resulting report, Mamás con Más (Mothers with More), identifies obstacles as well as possible solutions. What stood out, the authors noted, was that most of the mothers have a strong understanding of money management but encounter significant barriers to using mainstream banking services. Barriers included feeling unwelcome in banks as well as dealing with language gaps, requested documentation, and a lack of transparency regarding fees. Many found the institutional processes and documents confusing and off-putting. And then there were those whose budgets and income were so limited that they couldn’t afford, or see the sense in, monthly account charges or other fees.

Ofelia, for instance, is a single mother of two who makes money working in the fields and in child care. She went without a banking account for four years, she said, because she didn’t have enough money to support a minimum account balance. After participating in one of the study’s listening circles and having a lot of her questions answered, she found herself motivated to try again. She discovered a local bank that treats her well, with bilingual staff who recognize and greet her.

If the mothers in the project didn’t use banks but needed financial help, they turned to alternative services. These include payday loans, check-cashing services, money transfers, rent-to-own services, and car-title loans—services often considered predatory because they can charge steep fees and high interest rates.

What the researchers found was that Watsonville had more than twice as many alternative lenders as the city of Santa Cruz. Using these lenders can push families further into debt, so their availability should be limited or banned, the report recommended. In addition, there should be improved access to mainstream financial services. Unfortunately, said Cadenas, government social-service asset limit policies often discourage their use. “Various programs and policies designed to assist the poor actually discourage them from building credit and financial assets.” To address this potential barrier, the report recommended eliminating asset limits that can discourage families from using mainstream financial services. Providing useful and specific information such as this is helpful, said Robert Singleton, executive director of the Santa Cruz County Business Council. It can guide the development of business practices and policies that improve the region’s economy and “collective quality of life.”

For Victoria, an agricultural worker and mother of three, supports such as the ones identified by the study have gone far. She is benefiting from bank classes held by the Santa Cruz Community Credit Union as well as by MidPen. “Both helped me out a lot,” she said, adding that the credit union makes her feel safe and comfortable. The process of getting a car loan was difficult, but has made her more organized and careful, she said. “It’s a good thing to prepare for the future.”