A window to the early universe

Witnessing the birth of galaxies

The present day is relatively dull, cosmologically speaking. Most of the action happened in the first few billion years after the Big Bang, when enormous swirls of gas and dust collapsed down to produce the earliest stars and galaxies, filling the universe with their light. Half of today’s stars arose during this peak era of formation.

Teasing out the details of this active early epoch has proven difficult. It’s only recently that astronomers have switched on facilities like the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), one of the world’s most powerful radio telescopes, allowing them to draw back the curtain to very nearly the dawn of time.

“With these new tools we will be able to really map out the distribution of star formation in individual galaxies 12 billion years ago,” said J. Xavier Prochaska, UC Santa Cruz professor of astronomy and astrophysics and ALMA researcher.

Astronomers have used sophisticated computer models to develop ideas about this period. Simulations of the effects of dark matter and dark energy, plus the matter content of planets and stars, show virtual galaxies coalescing out of an unstructured fog. The results suggest that uneven distributions of massive dark matter drew gas and dust into galactic knots, where the material cooled and fragmented into stars. Astronomers have long awaited physical data to corroborate or challenge these views, and ALMA—which became fully operational in 2013—has begun to deliver.

Observatories like ALMA work in radio bands, searching for light coming from the glowing gas and dust present in the first galaxies. Only slightly warmed by young massive stars, this material is much fainter and further away than recently formed objects. ALMA, located in the Chilean high desert, can capture these light signatures with its large array of 66 massive antennas (“dishes”).

“It’s sort of a new window, and when you open a new window you see different physical phenomena,” said Christopher Carilli, who also studies the earliest galaxies at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, a major radio telescope facility in the U.S. that hosts the North American ALMA Science Center. Whereas most astronomical observations have been of stars, “the focus is now shifting to the source of those stars, and completing the picture of the conversion of gas to stars as a function of cosmic time.”

Some limited physical clues were already available. Strange cosmic beats called quasars formed during an even earlier period, sending out powerful light beams that intersected the later gas and dust, imparting characteristic signatures onto it. Astronomers have used these indirect observations to locate and study a few early galaxies.

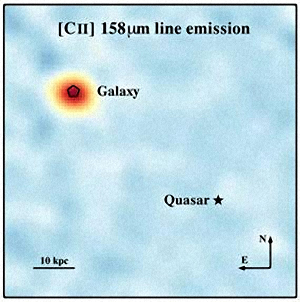

As reported by Prochaska and colleagues in a 2017 paper in Science, the more direct ALMA observations have produced surprises. For instance, quasar light had pegged one of the team’s galactic targets to a specific location. But ALMA placed the object about 100,000 light-years away, suggesting that the quasar light had passed through a much-larger-than-expected halo of gas and dust. The galaxy also glowed much brighter than predicted, indicating prodigious star formation of roughly 100 suns per year, 100 times greater than the modern rate.

And this is just one galaxy. These first observations mainly show that ALMA, built in part for this purpose, is capable of performing as planned. Prochaska and collaborators intend to follow this promising early work with close looks at the births of many more galaxies. “It’s inspired us to start a large survey of these phenomena,” he said. “That’s really how you learn and rigorously test these models of galaxy formation.”