Stiffing cancer

Within the body’s tissues, a framework of molecules called the extracellular matrix (ECM) holds cells together. As tumors develop in many types of cancer, this framework stiffens.

“A lump felt during a monthly breast exam does not necessarily reflect the number of cancer cells,” said Lindsay Hinck, professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology. “It reflects both the cancer cells and the stiffened extracellular matrix.”

ECM stiffening appears to block cancer progression by maintaining a balanced state, or homeostasis, of intracellular tension. Conversely, loss of this homeostasis can contribute to cancer progression by promoting tissue disorganization and metastasis.

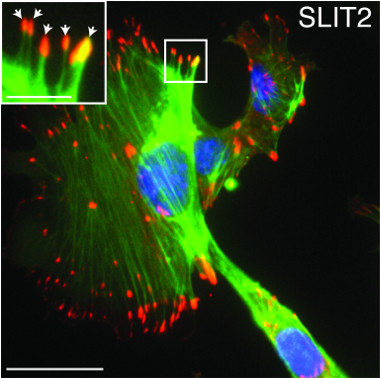

Hinck’s research focuses on understanding this complex biology. Senior author Hinck and collaborators now report that normal breast epithelial cells sense and respond to increased ECM stiffness by reducing levels of the microRNA miR-203, a short, noncoding RNA fragment that normally suppresses the Robo1 gene. This raises levels of the protein ROBO1, which, in turn, alters the cell’s cytoskeleton and boosts production of adhesion molecules, changes that help cells retain their shape and position within the stiffened ECM. The investigators also found that breast cancer patients with low-miR-203/high-ROBO1–expressing tumors had improved survival, identifying this pathway as a potential therapeutic target.