Sedimentary climate clues

To what extent has human activity contributed to today’s powerful storms and heat waves? To help answer this key climate change question, James Zachos, professor and chair of Earth and planetary sciences, looks to the past.

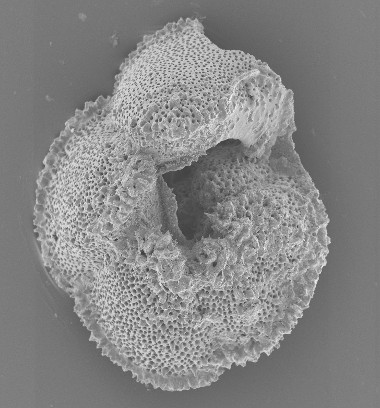

Fifty-six million years ago, during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), the Earth heated up 6° C and stayed warm for 150 thousand years. In a recently published study, senior author Zachos and collaborators analyzed ancient plankton shells from this period to reveal increasing ocean salinity and temperature. By producing greater evaporation near the equator, these changes would likely have led to more intense storms at higher latitudes and poleward shifts in dry and wet regions.

Although the heating during the PETM didn’t occur nearly as fast as today’s human-caused climate change, such case studies can be used to inform theories about how global warming will impact future hydrology. In California, for example, Zachos’s work supports models that predict more severe droughts and storms.

“We’re basically doing forensics,” said Zachos, who has been studying ancient ocean sediments for 30 years. “CO2 levels are going to go up, and climate specialists want to accurately predict how that will impact things like precipitation, so communities can plan.”