Lost languages

The task of saving indigenous languages has acquired increased urgency as more and more are threatened by emigration, rapid cultural changes, and the failure to teach native tongues to children.

Associate professor of linguistics Maziar Toosarvandani stands on the forefront of this effort. To preserve their rapidly disappearing language, Toosarvandani partnered with Northern Paiute speaking elders near Mono Lake—of whom only a handful remain. He’s now taken on the Santiago Laxopa variety of Zapotec, an endangered native language from Oaxaca, Mexico. Of the 100,000 Oaxacan immigrants who live in communities across California, including Santa Cruz, nearly all speak Spanish. Fortunately, some also speak Zapotec.

In their research, Toosarvandani and his team collect stories, oral narratives, and historical texts from which they infer the structure of the language. Then, by speaking Zapotec with native speakers, they test their hypotheses about its structure and collate their findings in an open access database integrated with a dictionary.

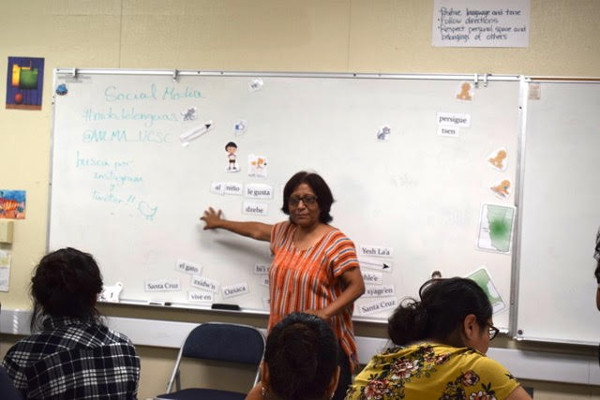

Toosarvandani and his colleague, associate professor of linguistics Pranav Anand, have also partnered with the organization Senderos to establish Nido de Lenguas, a nonprofit that sponsors monthly language classes and summer camps where native speakers teach their ancestral language to other Oaxacan immigrants. This work is vital, Toosarvandani said. “When we lose a language, we lose an aspect of what it means to be human. If we’re interested in saving the world’s diversity, we should be interested in saving these languages.”