Canvassing bacterial communities

Targeting biofilms to bust cholera

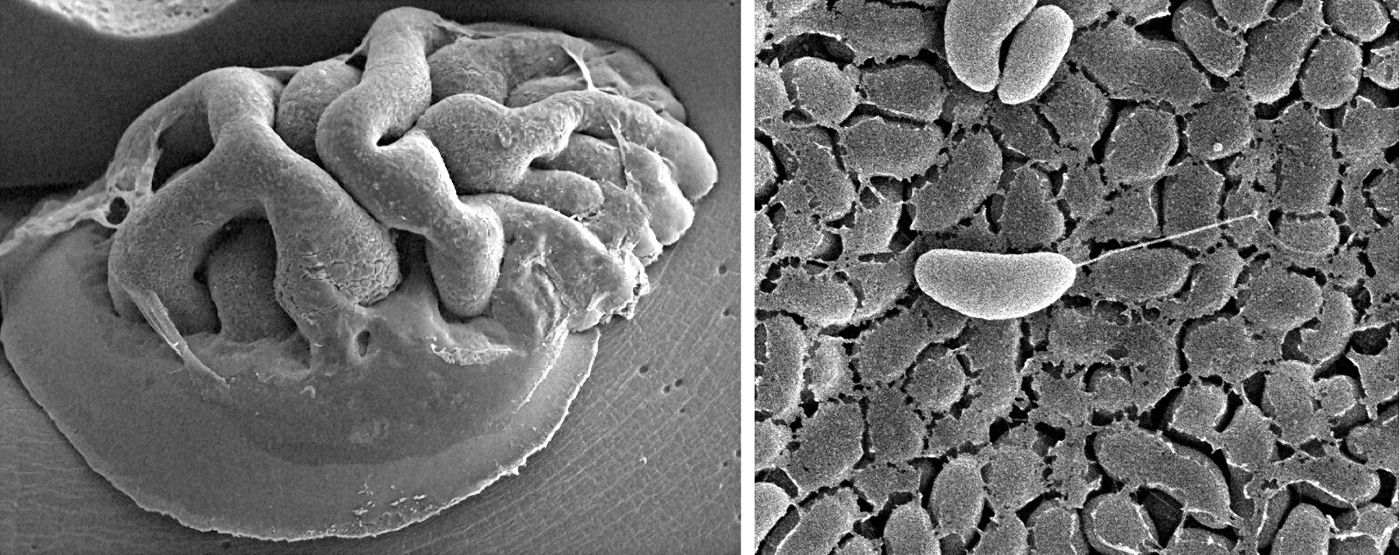

From above, the cholera colony looks like a piece of brain or a work of modern art. Deep grooves wind between wrinkly mountains of Vibrio cholerae bacteria. It’s tempting to reach out and touch this living landscape, but one swipe could kill. This is the same bacteria that sickens millions of people around the world each year, killing many of them, and it’s especially dangerous in its current form: a biofilm.

Bacteria are single-celled organisms; by definition they exist and function as lone entities. But to protect themselves from environmental stressors and optimize resources, groups of bacteria often interact, building communities held together with a kind of molecular glue. By virtue of their teamwork, their sheer number, and their structural properties, bacteria in these biofilms are more of an environmental nuisance and health hazard than populations of solo bacteria. That’s why researchers like Fitnat Yildiz, UC Santa Cruz professor of microbiology and environmental toxicology, are seeking to better understand biofilms. The goal? To develop new strategies to prevent biofilm formation and potentially discover new drugs urgently needed to combat the often antibiotic-resistant diseases caused by these bacterial communities.

“Scientists used to believe that most bacteria were free-living,” said Yildiz. “Now we know that the majority of bacteria live on surfaces in biofilms, and yet we understand very little of biofilm biology. There’s a lot to be discovered.”

Bacterial biofilms of one sort or another are everywhere: coating your teeth before you brush them and making your dirty dinner dishes slimy when they’ve sat in the sink overnight. They can grow so large they clog sewage pipes and cover the bottoms of ships. And they cause infections when they grow on the lining of a person’s lungs, gut, or urinary tract, or on contact lenses, pacemakers, artificial heart valves, or replacement joints. Yet the vast majority of all research on bacteria—including antibiotic development—is performed using bacterial cultures containing bacteria in their single, or planktonic, form.

By focusing on V. cholerae in biofilms, Yildiz’s lab has already revealed many of the major components of biofilms, including the molecules that make up the matrix—or glue—between the bacteria. The researchers have now turned their focus to how these components interact and how microbes know when to form a biofilm. “If you know what’s in the matrix and how all these steps are regulated, you can use it to your advantage,” said Yildiz.

Gripping and grabbing

In nature, cholera bacteria live in rivers and estuaries, alternating between a solo, free-floating “planktonic” state and biofilms depending on all sorts of poorly understood environmental factors including salinity, temperature, and nutrient availability. In general, though, it seems that harsher conditions promote biofilm formation, with the gatherings acting as a kind of safety net for bacterial survival.

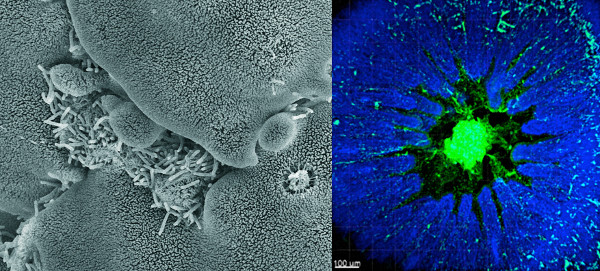

Like all biofilms, V. cholerae biofilms form on surfaces. They often coat the exoskeletons of tiny plankton, which explains why large plankton blooms often go hand-in-hand with cholera outbreaks.

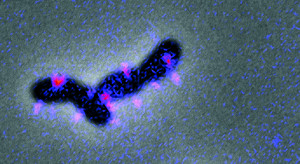

The first step in making a biofilm is when individual bacteria attach to a surface—whether on the shell of a plankton, the lining of your gut, or the interior of a sewage pipe. For V. cholerae and many other pathogens, clutching onto a surface involves pili—hair-like appendages that extend from the bacteria. Some types of bacteria also use pili to move, extending and retracting them like grappling hooks. V. cholerae, though, mostly rely on their single long flagellum—like the tail of a sperm—to swim in a fashion characteristic of the genus. When they first reach a surface, weak interactions between pili and the surface may cause them to move in small tight circles.

Without pili, bacteria like V. cholerae can’t attach to a surface and can’t form biofilms. So understanding how cells produce and control pili is critical to understanding biofilms. But there are more questions than answers about these miniscule limbs.

“Right now, we don’t know a lot about how the bacteria regulate the production of pili,” said Kyle Floyd, a postdoctoral fellow in the Yildiz lab. “We also don’t know exactly how they sense a surface.”

What is known is that a signaling molecule found only in bacteria, called cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate or c-di-GMP, is required for the cells to latch onto surfaces. In 2015, the Yildiz group discovered that c-di-GMP binds directly to a molecular motor that helps assemble MshA, the main protein component of pili. C-di-GMP, as reported in PLOS Pathogens, promotes the assembly of MshA, leading to new pili. The higher the levels of c-di-GMP, the more MshA is made and the more pili that can form.

To uncover more about this interaction, as well as what other molecules help V. cholerae sense surfaces and produce pili, Floyd is now labeling pili proteins with fluorescent tags, so he can see and study them in real-time. “Hopefully we’ll be able to watch them extend and retract,” he said. “And once we can do that, we can start manipulating other molecules and observe the effect on pili.” Learning how to stop bacteria from producing pili, he added, could lead to ways to completely block their ability to form biofilms.

The matrix revealed

A biofilm isn’t just composed of bacteria that gather on a surface, pili tightly gripping each other. To form a biofilm, the bacteria must produce the sticky molecular matrix that holds them together. Biofilm matrices are mostly composed of large sugar molecules called exopolysaccharides, but also include proteins, fats, and even bits of DNA.

In V. cholerae biofilms, Yildiz and her colleagues had previously shown that the major components are Vibrio exopolysaccharide (VPS)—about half the mass of the matrix—and the proteins RbmA, RbmC, and Bap1. In a recent collaboration with Carrie Partch, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, the researchers created mutant versions of RbmA that let them probe exactly how the protein contributes to biofilm formation. As recently reported in eLife, RbmA binds directly to VPS, helping to organize the exopolysaccharide structure.

“This was really exciting work,” said Yildiz. “It is the first direct interaction we’ve shown between matrix components.”

But that wasn’t all the RbmA mutants revealed. The team also showed that the protein has multiple possible forms—an open conformation and a more closed conformation, as well as a processed, shorter version. When the researchers mutated RbmA, locking it in the closed formation, the normally mountainous V. cholerae biofilm instead appeared smooth and shiny, suggesting a role in biofilm conformation. In the initial stages of biofilm formation, Yildiz hypothesizes, full-length, RbmA is required to switch between closed and open conformations to bind VPS and coax the sugar molecules into the right architecture for a strong biofilm. Later, when the biofilm is more structured, this relationship isn’t needed, and VPS takes on its shorter form. In this short form, the protein may have other functions, potentially including recruiting bacteria that aren’t yet producing VPS to join the community.

Another biofilm question the lab is focusing on is how VPS is produced in the first place. To address this, postdoctoral fellow Carmen Schwechheimer has homed in on two proteins with seemingly opposing functions—VpsO and VpsU. While the work is still ongoing, Yildiz’s group has shown that VpsO is a tyrosine kinase, an enzyme which adds a phosphate chemical group to tyrosine—a nucleic acid building block of proteins. VpsU, on the other hand, is a tyrosine phosphatase, which does the exact opposite—removing phosphates from tyrosine. In addition, VpsO itself switches between a phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated form. And when it does this, it appears to interact with VPS.

“It seems like you need that cycle of phosphorylation for the matrix to form,” said Schwechheimer. “If you delete VpsO, the bacteria don’t make exopolysaccharides and don’t form biofilms, so it’s clearly critical.”

Schwechheimer is working with professor of chemistry and biochemistry Seth Rubin and his lab members to create tyrosine-mutated VpsO variants. These should enable the researchers to determine which tyrosines in the VpsO protein are phosphorylated, and how the changes contribute to VPS production. The kinase, Schwechheimer said, is particularly attractive to study because it’s different from any of the native tyrosine kinases found in mammals, including humans. That means that drugs blocking VpsO—and biofilm production—would likely not impact the many tyrosine kinases that are endogenously expressed in the human body. “It definitely has potential as an antibiotic target,” she said.

Sending signals

Underlying all these molecular mechanisms is the central question of how bacteria first sense changes in their environment that trigger them to start building biofilms. “In bacteria, everything is about sensing and responding,” said Yildiz. “Cholera has to respond to all sorts of changes in its environment, from changing salinity in the water to a whole new set of factors when it’s ingested by humans.”

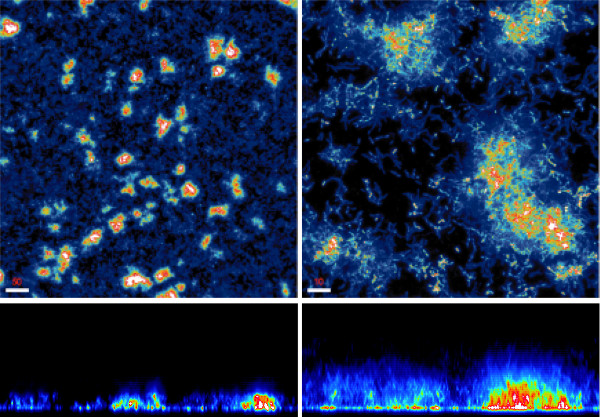

Researchers know that c-di-GMP is one of the important intermediaries in this sensory cycle, helping to communicate messages within bacterial cells. Its role isn’t just limited to producing pili, as Floyd is studying, but also appears to include biofilm and matrix formation more broadly. Studies by Yildiz and her colleagues over the past two decades have shown that high levels of c-di-GMP mean production of higher levels of a variety of proteins needed to produce biofilms. Currently, postdoctoral fellow Jin Hwan Park is leading a project to study how c-di-GMP inhibits V. cholerae motility and controls biofilm matrix production.

“C-di-GMP is a key, bacterial-specific signal for biofilm formation and maturation. Because it is not found in the host, it could make an outstanding drug target,” said George O’Toole, professor of microbiology and immunology at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine and another biofilm expert. Work by the Yildiz lab on c-di-GMP has inspired studies in his own lab, he added.

But exactly how c-di-GMP receives an initial signal to trigger biofilm formation remains unclear. Yildiz and former graduate student Andrew Cheng (now a senior scientist at Whole Biome, Inc., in San Francisco) wondered whether a two-component system might play a role. Common in bacteria, these systems are made up of two proteins—one that senses conditions outside the organism, and a “response regulator” that reacts, carrying out changes inside the cell. “Two-component systems are capable of sensing environmental conditions and telling bacteria how to adjust their physiology, so it certainly makes sense that these could be involved in biofilm formation,” said current graduate student Jennifer Teschler.

Teschler, Cheng, and Yildiz deleted all 52 known response regulators in V. cholerae, one at a time, and studied the effect of each deletion on the bacteria’s ability to form a biofilm. Seven of the response regulators, they found, impacted biofilm formation, with the biofilms developing abnormally in their absence. One, called vxrB, had never been characterized before so the researchers looked at it in more detail. Levels of vxrB, they discovered, impacted levels of c-di-GMP. Their findings, published in the Journal of Bacteriology, suggest that a two-component system involving vxrB could be one way that V. cholerae senses environmental changes, triggering, in turn, the increase in c-di-GMP that promotes biofilm formation.

Biofilm busters

In the U.S. alone, it’s estimated that every year nearly 2 million hospital-acquired infections involve bacteria in their biofilm state, costing health-care systems more than $10 billion. These infections are often resistant to antibiotics—in some cases, it’s hard for the drugs to penetrate the dense biofilms; in others, antibiotics simply don’t work against the altered molecular state of the biofilm-associated bacteria. When a replacement knee or hip becomes coated with a biofilm infection, a complication affecting as many as 2% of patients, the standard treatment recourse is repeat surgery to replace the prosthesis. In general, antibiotic resistance remains a critical and persistent public health concern, for which new drug strategies are urgently needed.

As with other bacterial pathogens, it’s clear that V. cholerae in biofilms are more infectious than bacteria in their planktonic form. A study in Bangladesh showed that using even a crude filter—such as one made from sari cloth—to filter drinking water can reduce the incidence of cholera by nearly half. That’s in part because such a filter removes the microscopic plankton that are coated with the most dangerous, biofilm-associated bacteria, Yildiz said.

When biofilm-associated V. cholerae are ingested, though, what happens to them in the human gut remains unclear. In a collaboration with Roger Linington, a former UCSC associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry now at Simon Fraser University, Yildiz discovered that bile acids, which break down fats in the gut, can disperse biofilms. But studies of cholera patients have found evidence of intact biofilms in their stool samples. This suggests that bacterial biofilms may be broken up during early digestion, but form again during later stages of infection. In the human disease setting, “There’s this interesting dispersal and reformation cycle going on,” said Yildiz. “And there are certain situations in which bacteria really need to form biofilms to be better protected, and other times it’s perhaps not as advantageous.” Studies focused on this important area, the molecular biology underlying V. cholerae biofilms in vivo, are being led by postdoctoral fellow Ana Gallego.

With Linington, who specializes in screening natural products for their therapeutic potential, Yildiz has helped identify other molecules that break up V. cholerae biofilms. She hopes this combination of natural chemical screening for existing anti-biofilm molecules plus working out biofilm biology to rationally design drugs will eventually lead to new antibiotics to treat biofilm-associated infections. Such drugs could stop pili from extending, keep exopolysaccharides from assembling to form a matrix, or block signaling by c-di-GMP, among other mechanisms.

And while Yildiz’s research focuses on V. cholerae, other researchers are focusing on the biofilms of other bacteria. At Dartmouth, for instance, O’Toole mainly studies Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which forms biofilms in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. He said, however, that V. cholerae is a good choice for this work. “V. cholerae is a terrific model. The factors that drive maturation of the biofilm for V. cholerae are conserved across a number of other microbes.”

As always, there’s a lot more research to be done. Not many biofilms in the natural world are composed of a single species of bacteria, Yildiz said. An additional important question for biofilm researchers moving forward is how different species of bacteria interact. Just as biofilm research has uncovered a more complicated biology than that associated with isolated bacteria, investigating how biofilms relate to the larger picture of microbiomes will likely add even more complexity. “Nothing lives in isolation, and—as with so much of biology—the challenge is going to be seeing what happens when we start increasing the complexity of biofilms,” said Yildiz. “Will everything we’ve found so far still hold true?”