Pen&Inq

By Emma Hiolski

Emotional Gaming

Although video games have now beguiled players for 40 years, we don’t have nuanced cultural conversations about them, said Katherine Isbister, UC Santa Cruz professor of computational media. According to Isbister, the language to support rich discussions—like those we have about books or movies—hardly exists.

In How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design, Isbister aims to give readers a clear understanding of how design choices influence the way players feel—and a way to talk about what’s happening and why.

Eschewing violent games, she instead analyzes video games designed to build empathy. Such games can provide a space for people to experience real emotional responses to both the choices they make and the subsequent consequences. The “emotional texture” of these games can closely match that of life, said Isbister.

“It’s worthwhile to develop literacy about games,” she said, “because they really are the medium of the 21st century.”

Hitting the Beach

Gary Griggs, UC Santa Cruz distinguished professor of Earth sciences, has spent a lifetime observing coasts. That’s where it all comes together, he said. “Over the years, I’ve worked on water pollution and dabbled in desalination, sand, dams, offshore oil, and nuclear power.”

In his ninth book, Coasts in Crisis: A Global Challenge, Griggs explores growing human impacts on coastal environments. Written to accompany his undergraduate course of the same name, the book also discusses the increasing dangers coastal hazards pose to swelling populations worldwide. Griggs makes sure to include a positive note—like the great strides made in wind and solar energy technology—at the end of every chapter. “We always have to have hope,” he said.

Griggs is also co-author, with Kim Steinhardt, of The Edge: The Pressured Past and Precarious Future of California’s Coast, in which they share tales of—and their personal connections to—California’s coastal history.

Between World Wars

During the 1930s, globalization was on the decline: countries cut ties with one another, the Great Depression was devastating the United States, and fascism was on the rise around the world. At least that’s the perspective that history books typically offer, said Marc Matera, UC Santa Cruz associate professor of history.

Matera and coauthor Susan Kingsley Kent shed a different light on the decade in The Global 1930s: The International Decade. They synthesize interdisciplinary readings from global scholars to share voices typically excluded from history books—those of women, minorities, and colonized peoples.

Through this new lens, they illustrate pervasive global connections between these marginalized groups during the 1930s. They also demonstrate that these connections formed a foundation for later global movements promoting decolonization and civil rights. “If we look at things from a different angle,” said Matera, “we can see that the global connections were as important as ever.”

Dream Theory

“Our minds are restless,” said G. William Domhoff, UC Santa Cruz distinguished professor emeritus of sociology and psychology. During waking hours, this is obvious: Our thoughts flit between current tasks to future errands or past problems. As it turns out, our minds do something similar when we sleep.

In The Emergence of Dreaming: Mind-Wandering, Embodied Simulation, and the Default Network, Domhoff explores nearly 15 years of new research on dreams and dreaming. He concludes that dreaming is an intensified version of mind-wandering.

Dreaming and mind-wandering activate specific, closely overlapping regions of the brain. When we dream, brain regions linked to imagination are activated and our sleeping minds “escape from time,” Domhoff said. And, while some suggest that dreaming is an evolutionary adaptation, he argues that imagination is the true adaptation. “We just happen to dream as a byproduct of that,” he said.

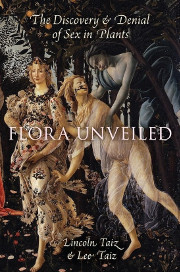

Plant Sexuality

Long after sexual reproduction in animals became scientific canon, plant reproduction remained a mystery. It wasn’t until the end of the 17th century that the idea of pollination and plant sex arose.

This discovery was “hotly debated” until the middle of the 19th century, said Lincoln Taiz, UC Santa Cruz professor emeritus of molecular, cell, and developmental biology. The primary objection, he said, stemmed from the strong association between plants and the female gender. Flowers and plants, like women, were supposed to be chaste and pure.

Taiz and his spouse, Lee Taiz—a former UCSC research biologist—spent 20 years traveling and unraveling this story. The result is Flora Unveiled: The Discovery and Denial of Sex in Plants.

“It is a fascinating topic,” said Lee Taiz, “and it says so much about cultural development and the way that culture either enhances or stands in the way of scientific fact.”