Beyond the Middle Passage

Intra-American trafficking magnified slavery’s impact

Between the early 1500s and the mid-1860s, millions of Africans were captured, sold into slavery, and transported to the New World to live out their days in bondage. The African diaspora is believed to have been the largest forced migration in human history, though “mass abduction” might be more apt. Nothing conveys the scale of it better than the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (TSTD). Hosted at slavevoyages.org, the TSTD provides details of almost 36,000 slave-trading shipments that took place over three centuries. It’s the most complete record we have of transoceanic slave routes and an essential tool for researchers. One prominent historian likened its impact on the study of slavery to that of the Hubble Space Telescope on astronomy.

But like the Hubble—before it was repaired by the crew of the space shuttle Endeavour—the TSTD suffers from a kind of myopia. True to its name, it only includes voyages that made the transatlantic crossing from Africa, the infamous “Middle Passage.” But slave shipping didn’t stop there. It continued full throttle on this side of the Atlantic, with thousands of vessels and voyages ferrying enslaved people to and from points within the Americas.

The TSTD isn’t alone in overlooking that second stage of slave shipping. “For a long time, most research on the American slave trade focused on the shipments coming into major slaveholding colonies, and those were almost all arriving directly from Africa,” said UC Santa Cruz associate professor of history Greg O’Malley. “It missed a big piece of the overall picture.”

The missing piece—the bustling intra-American slave trade—played a critical role in spreading slavery across the Western Hemisphere and embedding it deep in the economic and social foundations of the New World. To grasp the full scope of that commerce is to gain a broader understanding of the way slavery shaped life in the Americas, with repercussions that are still playing out today.

O’Malley has spent much of his career as a historian advancing that broader understanding. The work began in graduate school, when he built his own database of thousands of slave shipments in British Colonial America (the 13 North American colonies and British Caribbean islands) as part of his Ph.D. thesis. He expanded on that research in his 2014 book, Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619–1807, a wide-ranging look at intra-American slave trading and its economic, political, and cultural consequences.

Now he’s taking another step, pooling his data with that of fellow historians to compile an even larger database, to be added to the slavevoyages.org site later in 2018. With information on more than 11,000 voyages, the new Intra-American Slave Trade Database will fill a crucial gap in the historical record and provide an essential complement to the TSTD.

“The Intra-American Slave Trade Database will give us a far richer picture of the slave experience,” said David Eltis, professor emeritus of history at Emory University and one of the creators of the TSTD. “I think it will inform a wide range of historical scholarship.”

An unexpected detour

O’Malley had a very different project in mind when, as a Ph.D. candidate in history at Johns Hopkins University specializing in British Colonial America, he began scouting for a dissertation topic in 2003. “I was thinking about the complex mix of people in the colonies,” he said, “with a particular interest in the cultures that enslaved Africans were bringing to America.”

To understand those cultural currents, he had to get a handle on the demographics—who the enslaved people were, where they came from, and in what numbers. And the numbers weren’t adding up.

“I’d be reading a book, for example, that said there were 90,000 people of African descent in North Carolina on the eve of the American Revolution,” O’Malley said. “And yet the book cited only one slave ship carrying at most a few hundred people that had come to the colony from Africa. So where did those other 89,000-plus people come from?”

It was a glaring discrepancy, one that O’Malley ran into again and again as he surveyed the literature. “There was a lot of scholarship on the transatlantic portion of the slave trade, describing where people landed in the Americas from Africa,” he said, “but that data didn’t line up with where we knew enslaved people actually lived in the New World.”

He did have a hunch. There had to be an extensive shipping system that was moving people from a small number of arrival points—like Charleston, South Carolina, the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, and Kingston, Jamaica—to the many places they lived and labored throughout the Americas.

To confirm that hypothesis, O’Malley went to the only detailed records that still survive—British Naval Office shipping lists, where colonial officials dutifully logged the contents of arriving and departing ships at ports throughout British America. The innocuous-looking ledgers contained a grim accounting. Alongside entries for goods like sugar, rum, salt pork, and naval supplies, many had a column for “Negroes.”

O’Malley spent a year systematically cross-checking thousands of such records (most were available on microfilm at Johns Hopkins’s Eisenhower Library), tallying the shipments and creating his own growing database, which he modeled on the TSTD. “I had the notion even then that the editors of the TSTD might someday incorporate my data,” he said.

By the time he was done, he’d documented intra-American slave trading on a previously unknown scale—over 7,000 voyages from the 17th through 19th centuries. “The magnitude of it surprised even me,” he said.

Behind the numbers

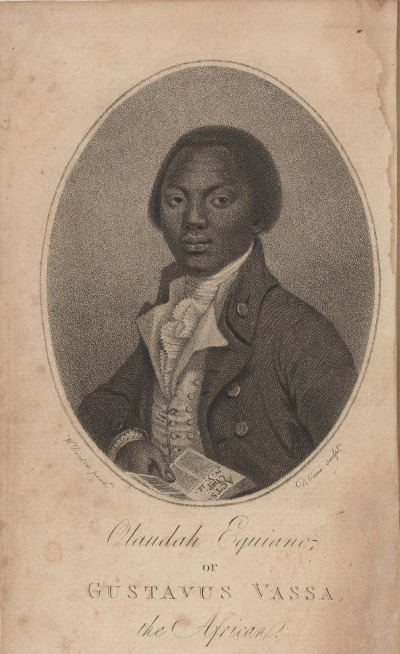

It was depressing work at times, and not only because of the sheer monotony of combing through shipping lists day in and day out. “There was a terrible tension between the boredom on the one hand and the realization that all those numbers flashing past on microfilm were human beings,” O’Malley said. “I really wanted to present a human story of what the captives suffered in this horrific business, but these documents are the opposite of humanizing.”

Eventually, by analyzing the numbers along with other sources such as merchant correspondence and slave narratives, he was able to flesh out a fuller story. In his Ph.D. dissertation and later book, he showed how, for many enslaved Africans, the transatlantic passage was just a segment of a longer journey. He estimates that more than 400,000 of the Africans brought to British American ports between the mid-17th and early 19th centuries were promptly packed aboard other ships and dispatched to distant parts of the Americas.

“Although some of the enslaved were purchased by plantation owners and put to work near where they made landfall, many were bought by merchant speculators who then transported them for resale elsewhere in the colonial world,” O’Malley said. In other words, the major ports served as hubs in a vast distribution network.

The busiest hubs in the British Americas were in the Caribbean, principally Kingston, Jamaica, and Bridgetown, Barbados. From there, large numbers of slaves were shipped to North American colonies or shuttled between various British Caribbean territories. Even more were exported to other colonial empires, going mostly to the French Antilles and Spanish settlements in South and Central America. “If you look at the transatlantic data alone, you see a few key hot spots,” said O’Malley. “But with this broader data set you get a more powerful sense of the real pervasiveness of slave trading.”

Longer journeys, greater hardships

For people who’d already endured the deprivations of the oceanic crossing, the further passages only added to the ordeal. The port records O’Malley examined showed many intra-American slave-trading ships arriving at their destinations with fewer captives than they set out with, owing to deaths en route. Comparing the numbers, he was able to calculate an average mortality rate of 5% for enslaved people on intra-American voyages. That’s lower than the estimated 20% who perished during the Middle Passage. “But given that the intra-American voyages were much shorter, it tells us that people were actually dying at faster rate,” he said.

Those who survived found themselves increasingly isolated with each step of the journey, as friends, family members, and people with common ethnic backgrounds who’d managed to stick together or form bonds during the trip from Africa were split up and sent their separate ways according to the needs of merchants.

As for the merchants themselves, many were middlemen who purchased enslaved people at their initial port of arrival, then resold them wherever they could fetch a higher price; in effect, buying wholesale and selling retail. “Most of the previous work assessing the economics of slave trading considered only the transatlantic trade. They looked at the price paid on the coast of Africa, the transportation costs, and the price received in America,” O’Malley said. “But this complicates that picture, adding a whole other round of buying, selling, and profits.”

A hidden logic

While the transatlantic trade was run largely by slave specialists, the players in this second layer of trafficking were often ordinary merchants happy to sell whatever the market wanted, be it raw materials, products, or people. Slaves were treated like livestock and frequently combined with other cargoes such as rum, timber, and cloth. The mix sought to maximize the returns on each leg of a ship’s travels.

This financial logic became clear when O’Malley studied the letters that merchants wrote each other as they negotiated deals and planned their shipments, and it helped explain trade patterns that at first glance seemed nonsensical.

He discovered, for example, that many of the slaves in North Carolina were being brought from Kingston, Jamaica. That helped to solve the original puzzle that started him investigating slave routes in the first place, but it begged another question. Why would anyone ship slaves all the way from Jamaica when there were plenty available in the neighboring colonies of Virginia and South Carolina? “It only makes sense if you look closely at the commerce,” O’Malley said. “Traders in North Carolina were exporting food and materials to the sugar plantations in the Caribbean, and they needed something to take back in return. North Carolina could only handle so much sugar and rum, but there was always a market for slaves.”

It was the imperatives of the marketplace, O’Malley argues, that spread slavery far beyond the plantation zones to many corners of the Americas, including areas we don’t typically associate with slavery today, like New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania.

Slave trading greased the wheels of commerce, and helped entrepreneurs get a toehold in new markets. While demand for other goods ebbed and flowed with supply, the need for workers was nearly unquenchable. The Americas offered up a seemingly endless bounty of land and natural resources. All that was needed to reap the spoils was cheap labor. Slaves became a widely accepted medium of exchange, a bargaining chip that merchants could trade for almost anything else.

“I found examples of merchants writing to each other, saying, ‘If you want to get into this business or that business, get some slaves, because there are always planters in need of labor who will deal with a slave trader,’” O’Malley said. “So if you wanted to get into the rice export business in South Carolina, the advice was, ‘Pick up some slaves in the Caribbean. There will almost always be a plantation owner who will sell his rice to you for slaves.’”

British manufacturers went a step further, using the cover of slave trading to break into lucrative Spanish American markets in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. At the time, Spain barred foreign imports to its American colonies, but made an exception for slave traders because of the pressing need for labor. The British exploited this loophole, gaining entry to Spanish American ports by bringing slaves for sale while simultaneously smuggling in mass-produced goods such as textiles. Selling those products was the real endgame. It gave a timely lift to British factories at the dawn of the industrial revolution and helped fuel a boom in manufacturing. (Many of the same manufacturers depended on raw materials supplied by slave labor in the Americas, especially cotton.)

Slavery at the center

The overview that emerges is of a slave trade thoroughly entwined with, and instrumental to, the economic growth of the colonized Western World. O’Malley’s research makes the case for what the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates calls “the centrality of slavery in American history.” In this view, slavery wasn’t an ugly footnote in the story of American prosperity and economic opportunity—it was a driving force.

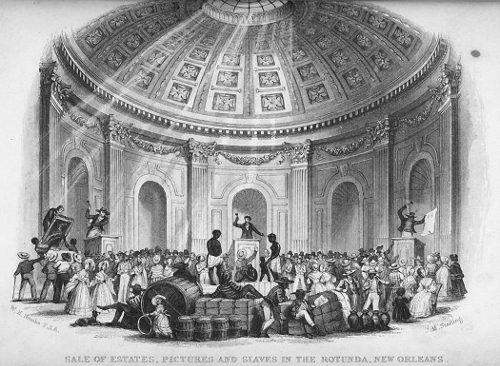

And it wasn’t just slave traders and slaveholders who benefited. It was everyone who shared in the wealth of the New World. The slave business went far beyond plantations, and touched all sorts of people. There were the sailors and dockworkers who transported slaves, the brokers and auctioneers who sold them, the bankers who handled the transactions, the farmers who sold provisions to arriving slave ships, and the ordinary consumers buying goods whose availability depended on slave trafficking.

This ubiquitous commerce had a normalizing effect, O’Malley believes. Many European Americans came to accept slavery as a necessary part of doing business and getting ahead, while turning a blind eye to the human toll. That indifference is painfully clear in the merchant letters. Amid pleasantries and small talk, the businessmen casually mention shipments of slaves, with no sign of empathy or recognition that these were actual people.

Illuminating past and present

The British American trafficking O’Malley studied was just a slice of the overall intra-American slave trade. Other colonial powers—Portugal, Holland, Spain, France—were doing their own trading, and a number of historians have been collecting data on those networks. For example, Alex Borucki, UC Irvine associate professor of history, has amassed details of roughly 1,000 slave voyages in the Portuguese colony of Brazil and in Spanish South America (areas that became Venezuela, Uruguay, and Argentina).

Funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant administered by the UCSC Humanities Institute, Borucki and O’Malley have been combining their data with that of other researchers tracing slave routes in the Dutch and Spanish Caribbean to create the new Intra-American Slave Trade Database. When the database goes live at slavevoyages.com later this year, scholars, students, and the general public will be able to search its 11,000-plus voyages using criteria such as the name of the ship, the date of the voyage, the itinerary, and even the outcome (for example, if slaves were successfully delivered or rebelled). “It’s really an astonishing expansion of the raw data we have,” said Linford Fisher, associate professor of history at Brown University. “It’s giving us a much deeper understanding of the mechanics of the slave trade in the Americas.”

Slave trafficking dates back to antiquity, but the mechanics that Fisher refers to reflected modern economic developments. As the intra-American slave trade grew, an entire ecosystem of merchant speculators took shape and inserted itself between slave suppliers and slaveholders. This middle layer of resellers valued slaves not as laborers, but as commodities, fungible assets used to exploit price differentials in markets (buy low, sell high). That cold-blooded calculus is manifest in the port records O’Malley examined. Their rows and columns offer no information on who the slaves were—not even their ages, genders, or origins—just quantities: the number of units shipped.

The reduction of persons to financial abstractions pushed the dehumanization of enslaved people to new depths. Plantation owners and overseers at least had to live beside and interact directly with slaves over extended periods. But for many of the merchants and others in the trafficking business—aside from the relatively small number of sailors and handlers who did the actual dirty work—the enslaved were mere line items on balance sheets.

This industrial-scale “human commodification,” O’Malley contends, was part of a “systematic devaluation of black lives that’s still with us.” He believes a reckoning is long overdue, and that historical research has a vital role to play. “My hope is that the work that I and other historians are doing helps American society finally come to grips with the legacy of enslavement and how it shaped the inequalities we see today,” he said. “If the information in this database can move us toward a more honest appraisal of our past—and our present—that would be the ultimate accomplishment.”