Beneficial binding

Prion diseases, including mad cow and, in humans, Creutzfeldt-Jakob, are fatal neurodegenerative diseases. They arise, usually late in life, from massive aggregations of endogenous prion proteins.

Compared to the hallmark aggregating proteins of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, “the prion protein is quite complex,” said Glenn Millhauser, distinguished professor of chemistry. “Its multiple domains with all sorts of chemical modifications point toward an important function in the central nervous system.”

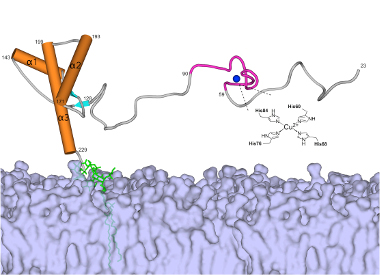

The bulky end of the prion protein binds to the surface of neurons where it modulates the flow of chemical messengers. Research has also shown that the extended, flexible end, in an unfolded configuration, drives prion toxicity and neuronal death.

Millhauser has been studying the prion protein structure for two decades. Of particular interest to him is how the protein binds copper ions. Scientists believe the protein binds copper to regulate the metal ion, which is essential for cellular function but extremely toxic if left unbound. Based on nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Millhauser and collaborators have now reported that copper, in turn, also regulates the prion protein by forcing its extended end to fold inward, thereby keeping its disease-related activity in check.