Lessons from teen activists

Youth organizations empower students

In the fall of 2012, returning Oakland High School students met with more than new teachers. They also encountered routine police patrols on campus and a new stop-and-frisk policy, enacted after several incidents of violence and weapons possession in the previous year. Students felt these new policies, along with teachers' established authority to hand out suspensions for "willful defiance," were unfairly targeting students of color. During the first quarter, school records showed that 32 percent of all student suspensions stemmed from willful defiance, which could cover anything from disrupting class to simply chewing gum or forgetting homework. Instead of just complaining, the students got organized.

Assisted by an Oakland-based grass-roots youth group, Californians for Justice (CFJ), the high schoolers surveyed their peers about the situation, compiled the results, and presented their report to the school principal. Other social advocacy groups used the students' report to pressure the Oakland Unified School District Board of Education to join Los Angeles, San Francisco, and other school boards to eliminate willful defiance as a reason for high school suspensions.

Reflecting on the students' involvement, UC Santa Cruz sociology associate professor Veronica Terriquez explained that "in [the] teenagers' minds, they don't necessarily think about their work as [being] political, especially when they start to get involved. It's about helping their communities."

Politicizing moments

Terriquez works in an emerging area of sociology, studying citizen-based organizations in low-income and historically marginalized communities. She's focused on civic youth groups, like CFJ, that work toward equality and racial justice. From statistically validated surveys and descriptive interviews, Terriquez catalogs the various ways youth can affect their schools and communities through these organizations. Her research also reveals the benefits these groups provide to students, such as the skills and mindset they develop, which can persist far past a student's initial involvement.

"There's a longer-term commitment by young people who have been civically engaged in their community—they tend to give back," said Terriquez, who observed this firsthand during work with an Oakland grass-roots organization after earning her bachelor's degree.

Terriquez's own politicizing moment came during the fight against passage of California Proposition 187, in the mid-1990s, which would have barred undocumented individuals from access to public services like non-emergency health care and public schools—to devastating effect in her community, she said. Ensuing work with community organizations guided her career toward "understanding how people could have a voice in their communities."

Individual impact

To identify the experiences and benefits students acquired from their involvement with CFJ and other youth organizing groups, Terriquez and her students surveyed youth in 98 civic groups associated with the Building Healthy Communities (BHC) program. This 10-year initiative was launched in 2010 by The California Endowment, a private health-oriented foundation based in Los Angeles, to analyze how funding community-based organizations can affect the overall health of 14 low-income urban and rural California communities.

It's not easy to elicit replies from high school students, but Terriquez's persistent approach resulted in a 92 percent overall response rate—a total of 1,396 surveys—that she keeps in an impressive collection of grey, orange, and turquoise file boxes around her office.

She credits her high survey return rate to partnering her students with interns from the organizations she studied. The interns also collaborated on the analysis of the surveys they helped gather—resulting in 14 reports crediting a total of 25 student and intern coauthors.

Active benefits

In her surveys, over half of the students reported participating in college preparation activities, improving their chances of enrolling in a two- or four-year college. But Terriquez also found that at least half the respondents said their grass-roots efforts helped them "a lot" in communicating, speaking in public, and understanding how government policies affect their own community.

Those kinds of soft skills can boost graduation rates because they equip students with strategies to help them stay in school, said Terriquez. Additionally, students' engagement with school boards and local governments helps them see their academic struggles as a result of systemic inequality, and not necessarily their personal failings.

Far from just shifting the blame away from themselves, this realization helps college students resolve their problems, Terriquez explained. For example, she found that students disproportionately took advantage of tutoring programs and Educational Opportunity Programs designed to assist students with their backgrounds.

Legacy lessons

Terriquez found that the effects of youth activism are lasting. Former members continue to be active in grass-roots groups at their colleges and within their community. Many of the students involved in changing their school's discipline policies went on to take active roles in the immigrant rights movement. "They weren't just participating," said Terriquez, "they were actually leading."

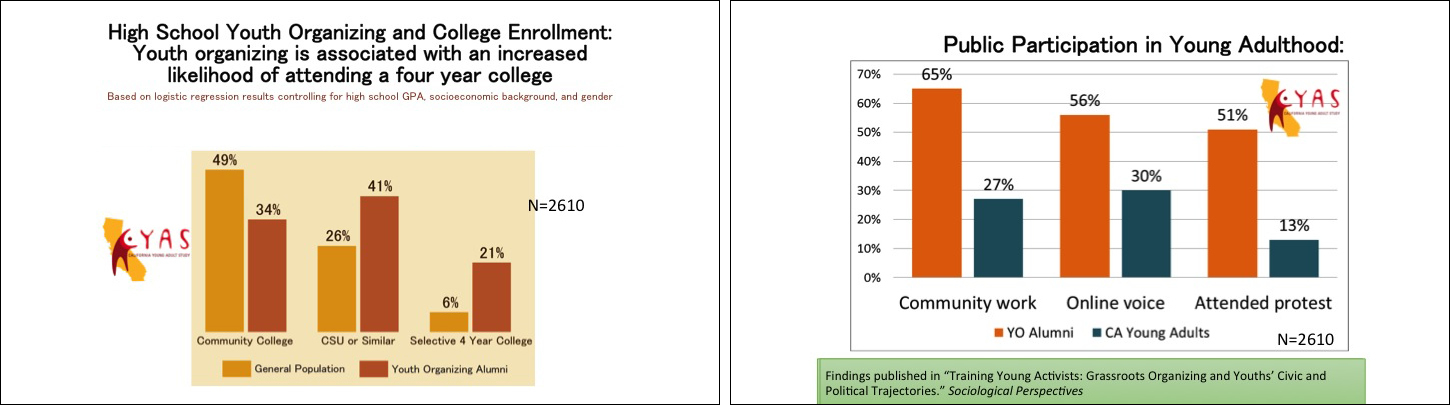

In a 2015 paper published in Sociological Perspectives, Terriquez compared the civic engagement of former youth organization members with the general population, based on records by the California State Fullerton Social Science Research Center in 2011. While former youth organization members were nearly twice as likely to come from low-income households—88 percent versus 46 percent of the general California population—they were statistically more likely to volunteer, be involved in community organizations, attend a protest, and vote. Terriquez credits this long-term effect to practical experiences gained at grass-roots organizations.

One example of these experiences, noted Geordee Mae Corpuz, lead organizer for the Oakland CFJ, occurred after the elimination of willful defiance suspensions in Oakland High. Students wanted increases in staff trained in restorative justice to lead students and teachers in conflict resolution. To fund this training, students joined their district's Local Control Funding Formula Advisory Committee. Established in 2013, this California program provides extra funds to low-income school districts based on accountability plans drafted by students, parents, and community members. The process of submitting the plans is very bureaucratic, and the Oakland students relied on CFJ's expertise to navigate the system. Corpuz said the participating teenagers met with parents across the district, people in the restorative justice movement, the school superintendent, and the budgeting office to draw up plans and secure the funds.

Additional qualitative data—revealed though analyses of Terriquez's trove of recorded interviews—show students from grass-roots organizations also develop strong social networks within their community. These students become knowledgeable about who their government representatives are, and often personally know the staff, she said.

Mining these interviews, which can be more than three hours long, offers an inside look at how students apply activism in their everyday lives. For instance, to learn how youth organization members engage with their parents about politics, Terriquez found incidences of youths reading through California's voting guides with their parents. She also found behaviors specific to each family's background; children of political refugees would assure their parents that political involvement in California was not dangerous in the way it had been in their home country, while children of undocumented immigrants would sometimes teach their parents about their rights in this country.

In her "control" interviews with random teenagers, Terriquez found that parents' interests and involvement in politics usually predicted their children's interest. This was not the case, however, with teenagers involved in civic youth organizations. "When children are very civically engaged, they politicize their parents," said Terriquez.

After school

Activist groups like CFJ also play a positive role in community health, believes Terriquez. Numerous studies show that decreasing high school expulsions and suspensions leads to higher graduation rates. Students who graduate are also more likely to pursue further education that, in turn, increases their earning potential and the overall health of their community.

Terriquez's research is being used to persuade educational and youth development funders to invest in similar programs. It's an area in which the California Endowment has heavily invested, said the youth program manager, Albert Maldonado Jr., but other funding organizations remain uncertain of its efficacy.

"We're learning that young people, with their spark and energy and passion, are critical change makers," said Maldonado "When assisted by youth organizing groups and adult allies, they can drive aggressive agendas," he said