Knot known

Rapid cell division relies on telomerase, an enzyme complex that makes DNA for protective caps on the ends of chromosomes. Despite decades of studies that link telomerase mutations with cancer, scientists don't yet have a structural model of the complex or know how it self-assembles in cells—a first step for developing drug targets or diagnostics.

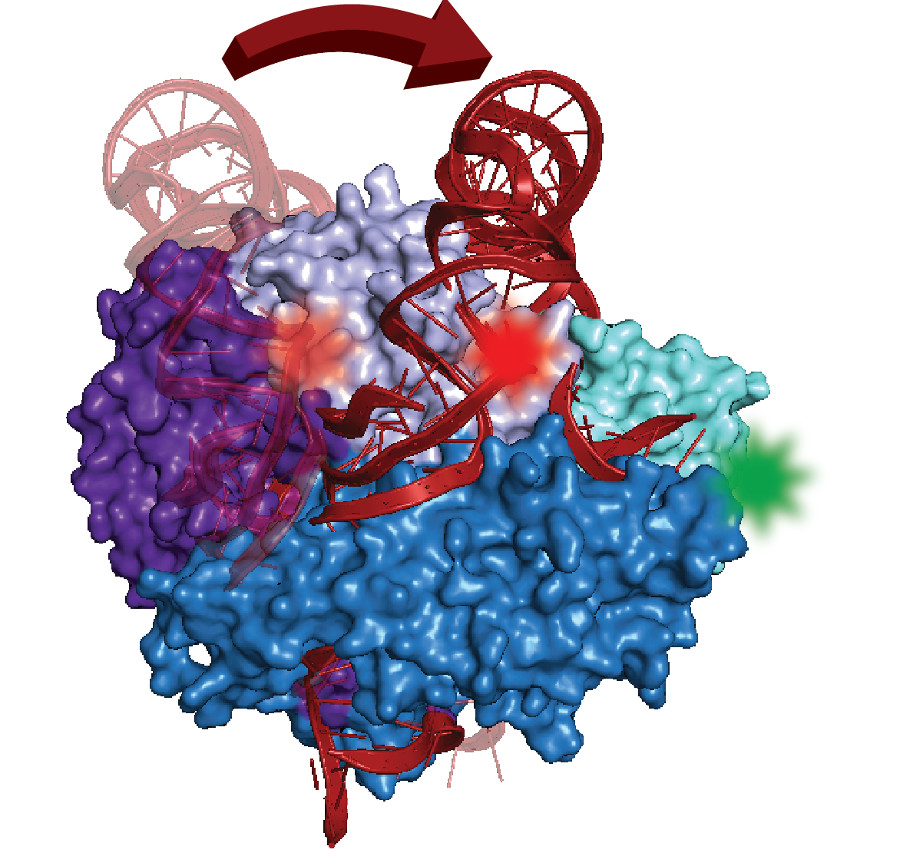

Made of protein parts and RNA, the complex contains a distinctively folded section of RNA called a pseudoknot. Found in many organisms, similar kinds of knots in other cell structures play key roles in promoting proper function.

With expertise in an advanced form of fluorescence microscopy that can measure structures one molecule at a time, UC Santa Cruz chemist Michael Stone and grad student Joseph Parks collaborated with computational modeling experts at Stanford to show a pseudoknot movement that occurred surprisingly far from telomerase's active site. "Whatever it's doing functionally, it must be acting indirectly," said Stone. The results are described in the journal RNA.

The bigger success of this study was combining single molecule measurements with computational modeling to find this pseudoknot movement, said Stone: "Telomerase is one of many protein-RNA complexes for which we don't know the structure. This is just the beginning."