Electric avenues

Sea creature studies improve human biosensors

About the last thing one would expect to find on the laboratory website of an engineer is a recipe for calamaretti saltati piccanti, an Italian entrée of sautéed baby squid. But it makes perfect sense when the lab is run by Marco Rolandi, associate professor in UC Santa Cruz's Baskin School of Engineering; it's a dish Rolandi watched his mother make when he was a boy in Savona, a seaport town in northern Italy. Now, Rolandi and his lab group swap recipes for squid-centric cuisine, in tribute to the mollusks that provide a key ingredient for their research: chitin, the compound that gives cephalopod beaks and pens their toughness.

Rolandi and his collaborators create novel transistors that employ chitin-derived substrates to modulate the flow of protons, rather than electrons as conventional transistors do. "What we have developed, with these transistors that move protons, is a means of communicating a current of H+, which is the hydrogen ion, to the body rather than electrons," said Rolandi. These "bioprotonic" devices are a critical step toward enabling electronic technology to communicate seamlessly with living systems—using nature's own language. Such devices can be used to study physiological processes or, perhaps, even alter them.

In addition to being a good proton conductor, chitosan, the water-soluble chitin-derived compound that Rolandi's group works with, is nontoxic, biodegradable, and can be processed sustainably. His team develops innovative ways of creating chitin composites with desirable mechanical properties such as strength or flexibility. Potential applications include producing an environment-friendly alternative to synthetic polymers, such as the polystyrene foam used for things like packing material—or surfboards.

The body electric

Transistors are what enable circuits to perform calculations and are the sine qua non of all the gadgets—mobile phones, smart watches, digital cameras, computers, game consoles—that figure largely in our lives. In a conventional transistor, special materials called semiconductors can be triggered to switch modes from conductor to insulator, manipulating the flow of electrons and electron "holes" (spaces that could be occupied by electrons but aren't). Integrated circuits—microchips—have millions of transistors, each of which can be either "on," meaning current is flowing, which corresponds to the binary "1," or off, meaning no current is flowing, which corresponds to the binary "0."

Electric current is also a major mode of communication among living cells. But water, which makes up as much as two-thirds of the human body and is a major constituent of all organisms, is not a good electron conductor. Charged atoms, however, such as sodium and potassium, which carry a positive charge, and chloride, which carries a negative one, move reasonably well in water. Thus, ions are the lingua franca of cellular communication in most living systems.

The challenge of interfacing electronic technology with the human body, then, is that subtleties in the information encoded in the current can be lost in the translation from electrons to ions. The situation is analogous to a traveler in a foreign country who doesn't speak the local language using broad gestures in hopes of getting his or her general point across; whereas someone conversant in the language can communicate in a much more nuanced way.

Pacemakers, for example, work by monitoring the heartbeat and then delivering periodic pulses of electricity to normalize its rhythm. However, at the interface between the probes of the pacemaker and the heart tissue the flow of electrons is translated into ions moving in the bloodstream in a nonspecific manner. "Basically it's just giving a jolt; it's not specific to any ion. And every ion in the body serves a specific function," Rolandi pointed out.

The hydrogen ion in particular plays a pivotal role in regulating a number of biological functions, Rolandi said. For one, the concentration of H+ in solution corresponds to pH: the greater the concentration, the lower the pH, and the higher the acidity. And pH is one of the factors that influence the excitability of neurons, he noted; an alkaline environment lowers neurons' threshold for firing while an acidic environment raises it.

This can cause problems. In epilepsy, for example, the heightened excitability of neurons causes waves of disordered neuronal activity to sweep through the brain, resulting in a seizure. Rolandi speculated that a bioprotonic device that could control the flow of protons, and therefore pH, could be used therapeutically in epilepsy or other disorders. "Right now we are at the stage where we should be able to understand better certain neurological disorders. And we're looking into whether we can monitor, and then perhaps affect, the excitability of neurons," he said.

In one study published in Nature Scientific Reports, members of Rolandi's UC Santa Cruz lab, led by postdoctoral researcher Takeo Miyake, and collaborators at the University of Washington (UW), demonstrated that such devices can be used to control pH-tunable biochemical reactions, such as the enzyme-triggered glow of fireflies. And in another, published in Nature Communications, a team led by UC Santa Cruz postdoctoral scholar Zahra Hemmatian created a hybrid device with a model cell membrane—complete with ion channels—that can precisely measure and control the flow of protons and, by extension, pH.

"Although we have mastered the art of electronic communication fairly well, the vast universe of chemical signaling remains virtually untapped," said Aleksandr Noy, a senior scientist focusing on bioelectronics and nanofluidics at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California. "Protons play a very prominent role in this signaling universe, and Marco's work on bioprotonic devices really paves the foundation for our efforts to harness this particular biological signaling language," Noy said.

Flukes and skates

Rolandi traces the evolution of using chitin derivatives to construct bioprotonic devices to a stroke of serendipity.

In the early 2000s, the quest to put more computing power into smaller devices by packing larger numbers of transistors into integrated circuits hit a plateau. "You needed to reduce the size of the transistor in order to pack more on a chip; they call it Moore's Law," Rolandi explained. And many people were worried that traditional semiconductor transistors would soon hit a "red brick wall" where further miniaturization was no longer feasible.

Interest in the potential of single molecule transistors was on the upswing, when, in 2002, a major fraud scandal undermined the credibility of the field. In a series of papers—published in preeminent journals—a researcher at Bell Labs falsified data to make it appear as though he had successfully coaxed organic molecules, which don't normally conduct electricity, to behave as semiconductors.

In the wake of the revelations, many researchers sought to distance themselves from that particular area of investigation. Rolandi decided to turn his focus to biological conductors when he established his first lab as an independent researcher at UW in 2008. "My curiosity was caught by this idea of proton conduction," he said.

Protons are special in that they're only a couple thousand times larger than an electron, so they behave in a manner that's somewhere between that of tiny particles and large ions. Their conductivity in biological systems, for example, involves the breaking and reforming of bonds—like square dancers doing a right-and-left-grand, clasping and releasing hands with each dancer in turn. "So it's kind of a concerted movement while most ions move only by diffusion. I'm a physicist by training so from the fundamental aspects this was very interesting to me," said Rolandi.

A series of synergistic collaborations led to the lab's current focus on using ion-conducting polymers derived from marine life. First, a postdoctoral researcher with expertise in synthesizing chitin-based materials joined Rolandi's lab at UW. Then a marine biologist at Harvard University, Joel Sohn—who has since become a senior member of his UC Santa Cruz group—approached Rolandi with the idea of measuring the H+ conductivity of a hydrogel he'd encountered in an odd sensory organ found in certain cartilaginous fish: the ampullae of Lorenzini.

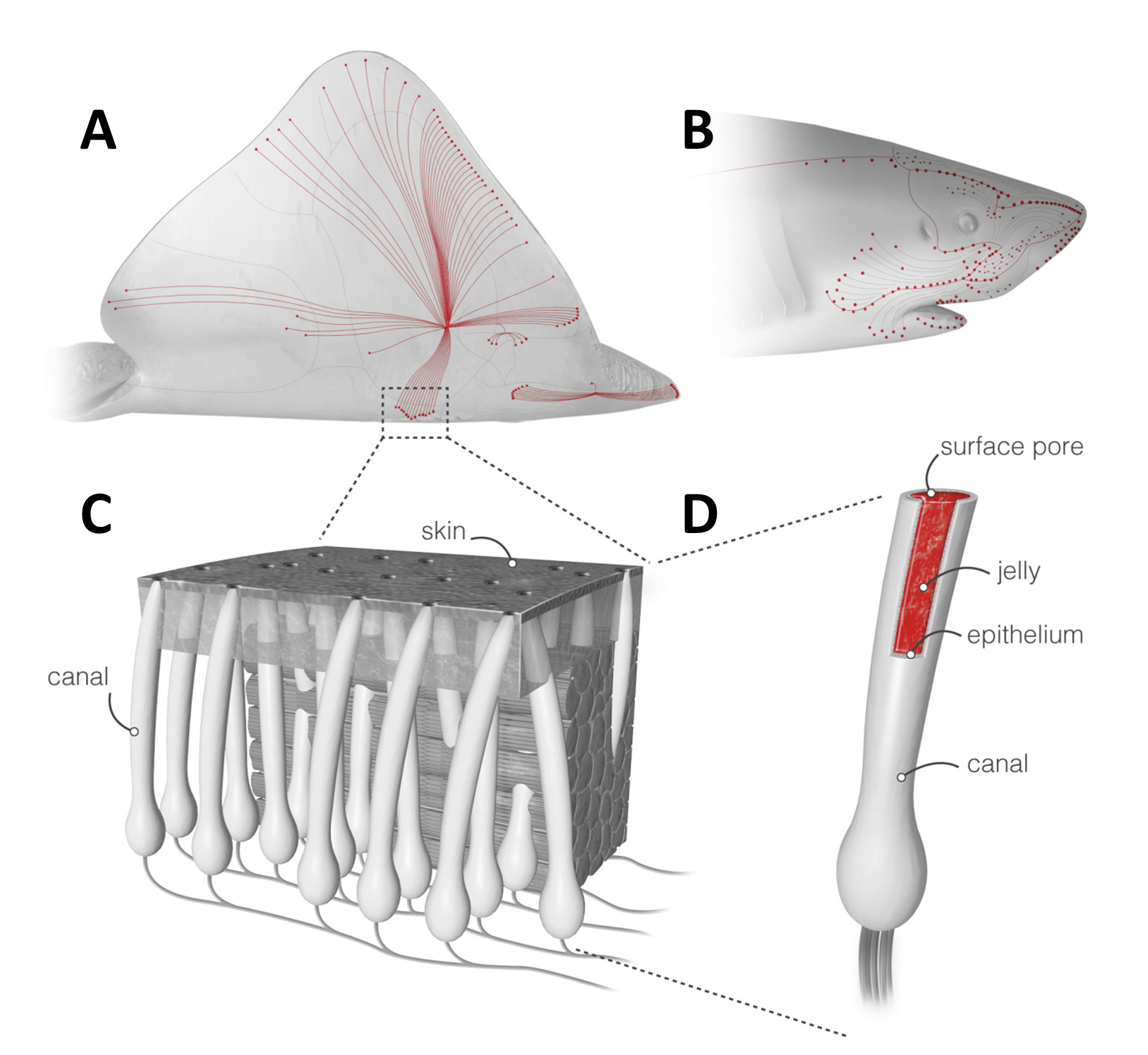

These organs may be the most sensitive electrosensors in the animal kingdom. They give sharks, rays, and skates the ability to pinpoint minute fluctuations in electrical fields—as small as five nanovolts per centimeter—generated by the muscle twitches and other physiological processes of creatures in the vicinity. This enables sharks and their ilk to locate prey in murky water or when their quarry is concealed.

The organ is actually an array of structures underneath the skin. Each ampulla is shaped like a Florence flask, with a round bottom containing cells that respond to electrical stimuli, a long neck filled with a transparent, viscous jelly, and an opening to the external environment through a pore in the skin. Externally, they appear as clusters of small dark spots, concentrated around the snout; an individual animal typically has several thousand pores.

Erik Josberger, a former doctoral student in Rolandi's UW lab, tested the jelly and to everyone's surprise it turned out to be a good proton conductor. Extremely good, in fact. This so-called "shark snot" has the highest known H+ conductivity in a biological material: three times higher than the maleic chitosan in the lab's bioprotonic transistors and just 40-fold lower than the state-of-the-art manmade polymer Nafion, which is used in fuel cells.

The exceptional proton conducting power of the jelly raises the question whether it's an incidental property of the substance, or integral to the way the electrosensing cells transduce the electric field change signal, Rolandi mused. But that's a question for biologists. The discovery relates to the lab's core bioprotonics work insomuch as it utilized the strategies they've developed to measure proton conductivity of biomaterials (for example, using palladium hydride contacts that can inject and collect protons).

A better board and beyond

Chitin is the second most abundant natural polymer (after cellulose) on the planet. In addition to strengthening the beaks and pens of cephalopods such as squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish, chitin comprises a major component of the exoskeletons of insects such as grasshoppers and cockroaches, and crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp, and lobsters. Globally, the food industry produces between six and eight million metric tons of crustacean carapaces annually, with a chitin content that ranges from 15 to 40 percent.

Led by graduate student Xiaolin Zhang, members of Rolandi's lab devised methods for tweaking the mechanical properties of chitosan composites—to make them either rigid or flexible, for instance—for a variety of applications, described in a paper for Journal of Materials Chemistry B. The team's initial idea for a consumer product is to make the unshaped "blanks" for surfboards, which are typically made from polystyrene or polyurethane. The manufacturing process for those synthetic polymers pollutes the environment, and the discarded boards take up space in landfills, releasing toxic chemicals when they decompose. "And obviously most people who surf love the ocean," Rolandi asserted. "So the last thing that they want to do is actually further increase pollution with their sport."

Graduate student John Felts, who recently won a UC Santa Cruz "elevator pitch" competition with the idea, is spearheading the surfboard project. So far he has collected some proof-of-concept data that Rolandi said demonstrates that their shrimp chitin foam can match the mechanical properties and performance of the blanks currently on the market.

But the longer-term plan is to produce any kind of foam from chitin, for products ranging from packing "peanuts" to disposable coolers. The upward trend in online consumer spending means more goods are being packaged and delivered to homes and businesses. "The amount of foam waste this generates is really a problem," Rolandi lamented. "If we can eventually make stuff like that out of shrimp shells, you can see how the environmental impact is much smaller."

Or, perhaps, lobster shells? In point of fact, the chitin that Rolandi's team uses is not extracted in the lab, but that hasn't kept him from considering the gastronomic possibilities of expanding his research—or collecting recipes for surf and turf.