Disarming Bacteria

Microbiologist searches for next-generation antibiotics

When bacteria that cause maladies like typhoid fever, pneumonia, the plague, or even run-of-the-mill food poisoning get inside your body, they're quick to mount an offensive. The invading pathogens assemble minuscule syringe-like structures on their surfaces, filled with armies of toxic molecules ready to infiltrate. Then, when the bacteria sense that they're in the right place, these syringes—called type III secretion systems—poke directly into your cells, injecting their contents inside.

These microscopic "injections" are one of the first steps of infection for some species of bacteria, letting the bugs hijack your cells. Understanding how these injections work may hold the key to developing new antibiotics.

"Type III secretion systems are used by dozens of bacteria that cause a lot of morbidity and mortality in the world," said Vicki Auerbuch Stone, UC Santa Cruz associate professor of microbiology and environmental toxicology. "What we want to do is disarm the system."

Over the past few years, Auerbuch Stone has discovered a handful of compounds that shut off the type III secretion system. The drugs, she speculates, may be able to render disease-causing bacteria harmless to humans without killing the pathogens—or the body's beneficial bacteria—in the process, a distinction that could eliminate some of the problems with existing antibiotics.

"There's reason to think—at least, based on what we've seen in mouse models—that type III [secretion] inhibitors could be very effective against disease," said Auerbuch Stone, who recently published a series of papers on how one inhibitor works.

A need for new drugs

Classic antibiotics—most of which have been used clinically for many decades—work by stopping the growth of bacteria or killing bacterial cells outright. But bacteria can evolve resistance to these drugs; every year in the United States, more than two million people become infected with antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The rising number of drug-resistant pathogens has been called a crisis by scientists and policy makers.

On top of that, these broad-acting antibiotics kill more than just the illness-causing germs that have gotten into a person's body. They also act on some of the trillions of other bacteria that are living in the body—the microbiota or microbiome. "We're just in the last five or so years realizing how bad it is to disrupt our healthy microbiota," said Auerbuch Stone. "And classic antibiotics do just that; they at least temporarily disrupt the microbiota."

With those challenges in mind, scientists like Auerbuch Stone are hunting for a new kind of antibiotic, dubbed "antivirulence" drugs. These new drugs block the ability to cause disease without killing bacteria. That's important because when bacteria are killed outright by drugs, any infectious culprits that develop a mutation to avoid that fate can very quickly spread; these living bacteria can reproduce while the ones killed by drugs can't. So, letting bacteria continue to live and grow, while taking away their ability to cause disease, gives bacteria with resistance mutations less of a competitive edge, scientists hypothesize. And targeting the virulence mechanisms—which are only used by pathogenic bacteria—could also spare the healthy bugs in the microbiome.

"I think there's really a need for new antimicrobials, and so-called antivirulence compounds make a lot of sense biologically," said James Bliska, a molecular biologist at Stony Brook University in New York, who also studies the type III secretion system.

Earlier this year, the World Health Organization published a list of "priority pathogens" that pose the greatest threats to human health. The top three are all Gram-negative bacteria that cause some of the hardest infections to treat—and are also those most prone to developing antibiotic resistance.

Named for their appearance under the microscope, these bacteria have an extra membrane surrounding them, making them especially good at keeping out existing antibiotics. That's one reason Auerbuch Stone's work with the type III secretion system is so important—the tiny syringe system is found specifically on Gram-negative bacteria, including the well-known bugs E. coli, Chlamydia, and Salmonella.

"There are a lot of challenges surrounding these particular bacteria and there hasn't been a new antibiotic for Gram-negative bacteria in a very long time," said Auerbuch Stone. Although penicillin was commercialized in 1938 and a flurry of other antibiotics hit pharmacy shelves in the decades following, no new classes of antibiotics that work on Gram-negative bacteria have been introduced since 1968.

Stopping the syringe

Since launching her lab at UC Santa Cruz in 2009, Auerbuch Stone has focused on unearthing compounds to block the type III secretion system. She's worked mostly with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a Gram-negative bacteria which causes food-borne illness. Her hope is that Y. pseudotuberculosis is a good model for all bacteria that rely on the injection system to infect humans.

"Ideally, some inhibitors will work in all bacteria that require the type III secretion system," said Hanh Lam, a UC Santa Cruz postdoctoral researcher in Auerbuch Stone's lab who's currently leading the project. "But we expect some will only inhibit certain bacteria."

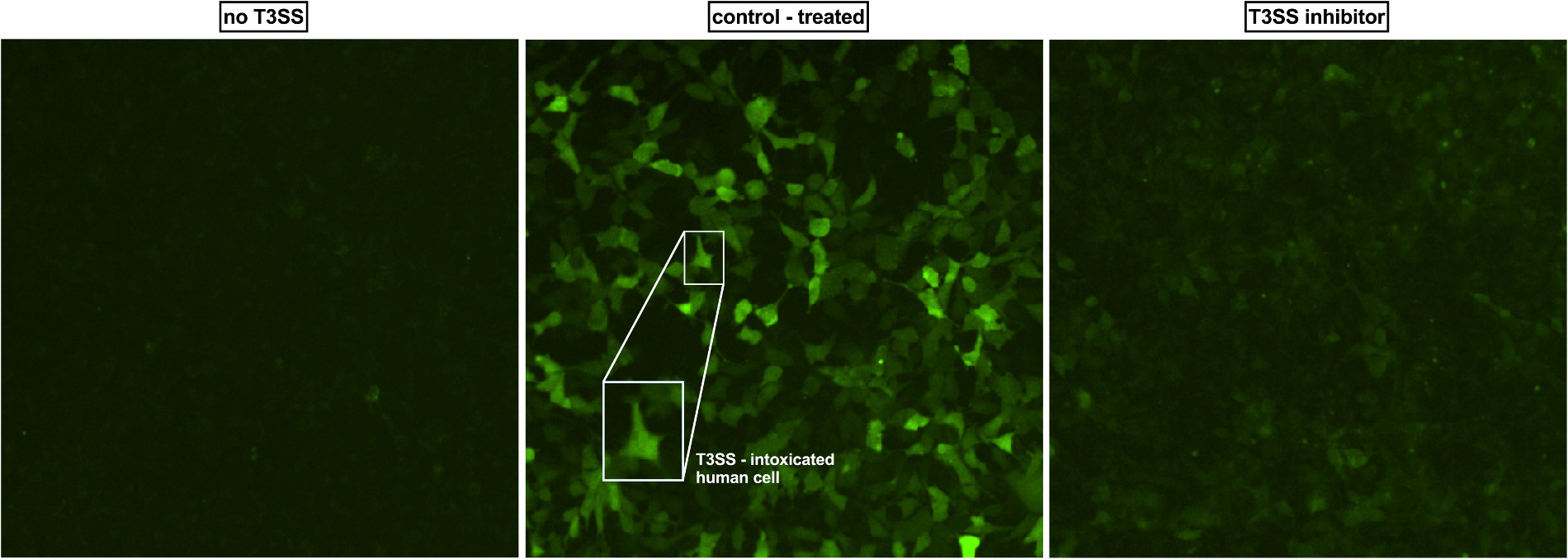

Auerbuch Stone and Lam developed and fine-tuned a method to quickly screen large collections of molecules to find ones that block one aspect of the type III secretion system. Their approach tests whether Y. pseudotuberculosis produces and expels YopE (Yersinia outer protein E), one of the so-called "effector molecules" that the bacteria normally injects through the type III secretion system syringe.

The researchers put Y. pseudotuberculosis in a liquid that mimics the inside of the human body and then test whether—in the presence of new drugs—the bacteria can secrete YopE into the liquid. If the bacteria can still do this, the type III secretion system is functioning as normal. But if not, a drug they've added must be blocking some step of the system. They then run a series of experiments to see whether the effects still hold true when the bacteria are interacting with mammalian cells.

Promising candidates

Armed with their screening method, Auerbuch Stone's group collaborates with three chemists who each have libraries of molecules that can be mined for drug discovery: at UC Santa Cruz, Scott Lokey synthesizes brand new molecules based on existing natural products and Phillip Crews isolates compounds from marine sponges, while Roger Linington, formerly at UC Santa Cruz and now at Simon Fraser University in Canada, collects molecules from marine bacteria during scuba dives.

In 2014, the researchers published their first success story; their high-throughput screen flagged two related molecules called piericidins, originating from marine bacteria, as type III secretion system inhibitors. When either of the piericidins were added to a culture of Y. pseudotuberculosis, the bacteria continued to grow but didn't eject the toxic compounds—including YopE—that it normally uses to hijack human cells. Since then, they've identified a handful of other molecules that have similar effects, and even found a drug that works in multiple species of bacteria. Those results are currently awaiting publication.

"I think one of the reasons we've had success is that these are libraries no one has screened for type III [secretion] inhibition before," said Auerbuch Stone. "Other people have screened standard commercial libraries."

The team has gone on to develop a set of assays to help pinpoint how molecules like piercidins affect the secretion system. Using special stains and microscopy techniques, they can visualize the syringes that are formed on the outside of Y. pseudotuberculosis. That's how they discovered that piericidin A1, one of the marine bacterial molecules they homed in on earlier, works by blocking the assembly of the needle, reducing the number of type III secretion needles on any given bacterial cell.

Other inhibitors, though, could block other steps, allowing the needle to form but preventing it from injecting human cells, for instance. The finding on piericidin A1 was published this year, in the journal mSphere, and helps pave the way for more work on how to develop it as a potential antibiotic.

Next steps

Some of the remaining questions on type III secretion underscore just how little is known about the system. "We really don't fully understand how the type three secretion system works," pointed out Lam. "We don't know all the steps it uses to orchestrate all these proteins and then secrete these toxins in the order it wants."

But Auerbuch Stone thinks her inhibitors—even in advance of any clinical implications—might shed light on the basic science of type III secretion. An inhibitor can help reveal which bacterial cells in the body are using the system at any given time, and when during the course of an infection the secretion system is key.

"Our lofty goal is that we'd like a whole suite of inhibitors that each block different stages of secretion," said Auerbuch Stone.

As for moving the inhibitors to the clinic, that's still years away. So far, inhibitors of the type III secretion system have only been shown to be effective in isolated cells or mice, not in people.

"Ultimately, the next step is the harder step, which is testing out the activities of these inhibitors in a more complicated assay or preclinical model," said Stony Brook's Bliska, referring to the inhibitors described in published research papers by Auerbuch Stone's group.

Auerbuch Stone admitted there are still major questions about the feasibility of using type III secretion inhibitors to actually treat infections. For instance, the effector molecules or virulence factors that are churned out by the system may only be needed for a bacteria to initially infect someone's body, not to keep an infection going. "So it might be that giving this kind of inhibitor during an established infection won't treat it," said Auerbuch Stone, "but it could work as a preventive."

As the number of antibiotic-resistant infections around the globe continues to grow, though, increased pressure will be put on the pharmaceutical industry to develop new types of antibiotics. This, speculated Auerbuch Stone, might make more scientists take an interest in type III inhibitors.

"A lot of the diseases we're talking about have really only affected the developing world, which has made them not get the attention they might have otherwise," she said. "As they become more of a global threat, I think people are going to have to start caring."