Brief inquiries

Mollecular Biology

By ribosome rewarded

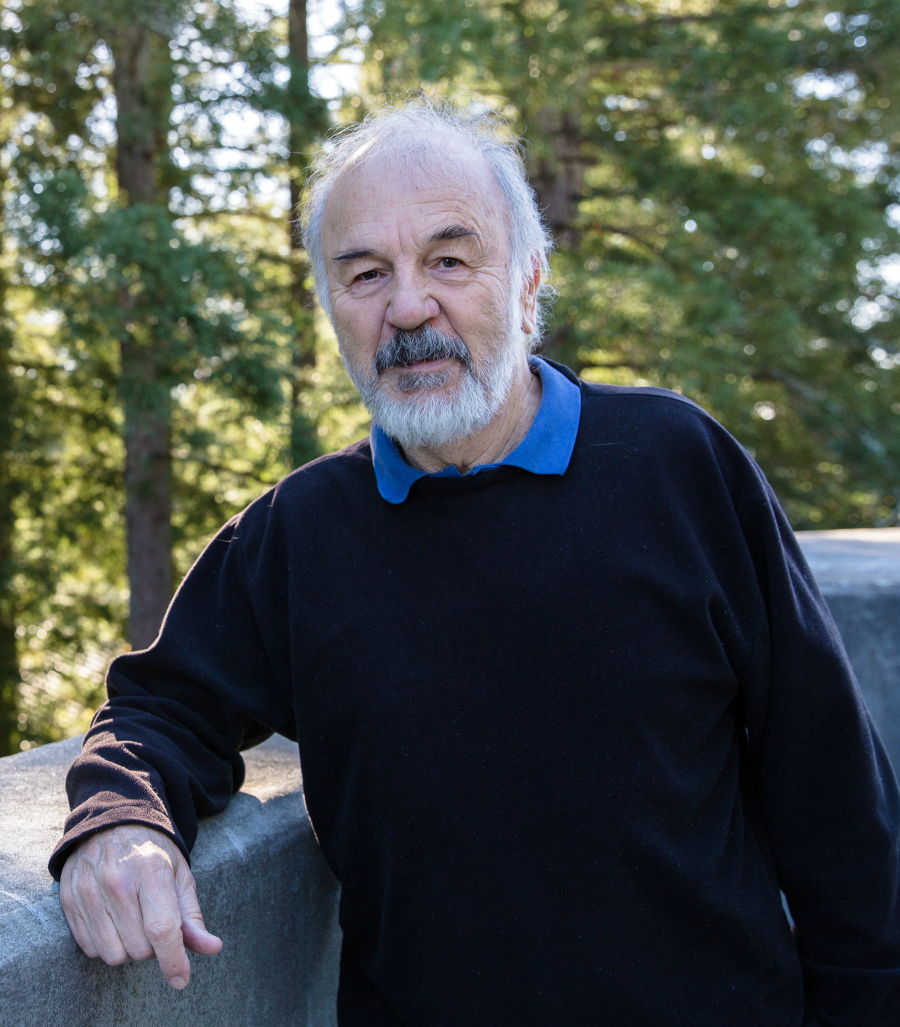

For revealing the central role of ribosomes in creating life through RNA and proteins, Harry Noller, Sinsheimer Professor of Molecular Biology, won the 2017 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. The $3 million award is funded by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to support the sciences.

“I can’t think of a more meaningful way to spend one’s career than working on the ribosome, one of the most amazing objects in all of the universe,” said Noller.

Since 1972, when Noller first showed that RNA was essential for ribosomes to produce proteins, his studies have spotlighted the role of RNA—not DNA—in the origin of life. In 1999, his lab produced the first high-resolution image of the molecular structure of a complete ribosome, a feat upon which they later improved.

“Our long-term goal is to create a three-dimensional movie of the ribosome carrying out protein synthesis at the atomic level,” said Noller, who plans to continue at the lab despite his emeritus status. Pinpointing structural changes during protein production could provide clues to how complex life arose from simple combinations of atoms, heat, and water. “It’s a tall order,” said Noller, “but it’s not crazy.”

Biomolecular Engineering

Cutting edge

In normal cells, mRNA splicing can edit a single sequence of genetic material in various ways, making transcripts for many different proteins.

Increasingly, studies have shown that aberrant splicing induces widespread transcript changes in associated cancers, noted Angela Brooks, UC Santa Cruz assistant professor of biomolecular engineering. For the first time, in a study published in Cancer Cell, Brooks and her colleagues linked one specific change in the splicing complex to a functional effect.

The SF3B1 mutation alters a single protein in the splicing complex. With Brooks’ expertise in computational analysis of mRNA transcripts, researchers uncovered an SF3B1-induced change in the DVL2 gene, which, in turn, activated a cancer pathway previously known as a factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but not known to be activated by SF3B1.

Now Brooks is developing high-throughput assays to simultaneously test the functional effects of hundreds of mutated RNA transcripts. She’s also focused on better understanding the splicing mechanism.

“Even in normal tissue we get different splicing patterns and we don’t really have a grasp of what’s happening,” she said.

Economics

College chances

Will lottery winners spend their windfall on college education?

Only if they win big, according to UC Santa Cruz economists George Bulman and Robert Fairlie, in a working paper published through the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“College is a big capital investment that drives government programs, tax exemptions, and life outcomes,” said Bulman, whose research focuses on why people choose higher education—or not.

U.S. Census Bureau data shows that 63% of students from high-income families attend college compared with 36% from low-income families. This disparity is often attributed to college costs and constraints to getting loans, said Fairlie.

After analyzing federal tax records linked to federal financial aid awards for more than one million children whose parents won $600 or more in the lottery from 2000 to 2013, they found wins less than $100,000 had little effect on college enrollment. Surprisingly, payouts that exceeded the cost of college continued to increase the probability of enrollment; the effect of a $1 million win was much larger than that of a $500,000 win. “Maybe it’s not all about money,” said Fairlie.

“We may need to do more to show people the value of education.”

Computer Science

Linked up

Making sense of big data can be a big problem. Information comes from disparate sources with bias, collection and missing data issues, noted Lise Getoor, UC Santa Cruz professor of computer science. So how do you build methods that can integrate this data and make interesting (and valid) inferences?

A Fellow of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, Getoor founded a line of research called statistical relational learning. Her methods mix network information with statistical information, exploiting background knowledge and domain theory as well—mapping, for instance, the underlying power structures among corporate entities or predicting outbreaks of social unrest.

For such work, Getoor and her collaborators developed an open-source, probabilistic soft logic (PSL) tool, that can represent structure and uncertainties in networks, and make inferences in a scalable way—at orders of magnitude faster than competing approaches. The latest PSL release occurred this year.“The key thing about my work,” said Getoor, “is that it not only makes use of probabilistic information, it also makes use of relational information, uncovering links and ties among all kinds of data.”

On the flipside, Getoor and her group also study privacy issues—learning how to prevent unwanted linkages.

Planetary Science

Heavy hearted

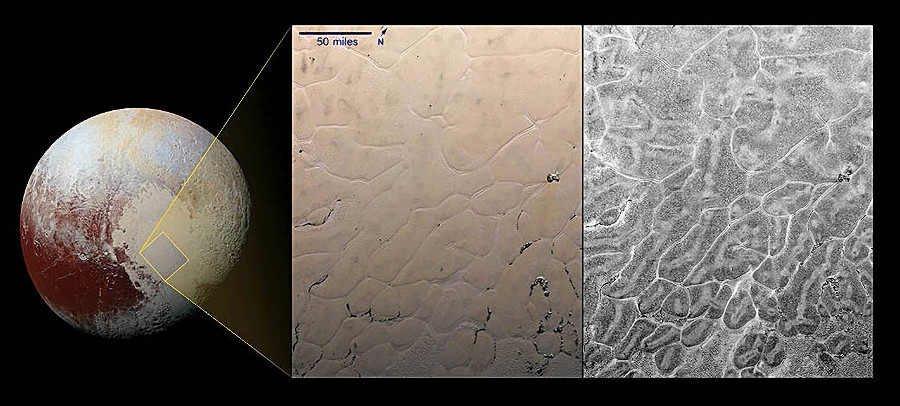

It's no coincidence that Sputnik Planitia has a special place in the heart-shaped surface feature on Pluto. The big basin, flooded with nitrogen ice, lies almost exactly underneath and opposite Pluto's largest moon. Holding that nearly-equatorial spot requires a lot of extra weight, noted Francis Nimmo, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz. The question was, in a 1,000 kilometer-wide hole, where was that heft hiding?

"A subsurface ocean is the easiest way of getting extra density, since water is denser than ice," said Nimmo, making that case in a paper published in Nature. Returning with images of fractured surfaces all over Pluto, NASA's New Horizons mission helped resolve the hidden ocean question, a possibility Nimmo previously described in a 2011 paper. If a big impact dug out the basin, the ice removed would be replaced with denser water from an ocean below. The slow expansion of the freezing water closer to the surface would crackle the sphere's crust.

"We're finding more oceans in the outer solar system," said Nimmo. While they could indicate habitability, he's more intrigued by the fundamental science: "With the information we have, what can we learn about these icy bodies?"

Chemistry and Biochemistry

Knot known

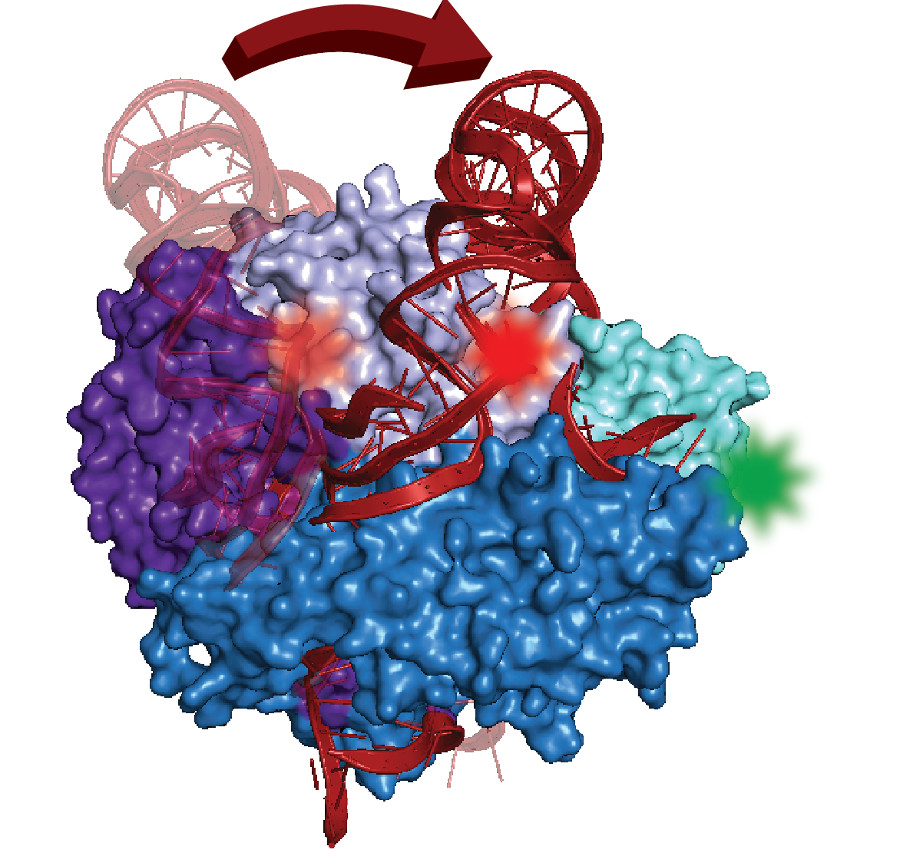

Rapid cell division relies on telomerase, an enzyme complex that makes DNA for protective caps on the ends of chromosomes. Despite decades of studies that link telomerase mutations with cancer, scientists don't yet have a structural model of the complex or know how it self-assembles in cells—a first step for developing drug targets or diagnostics.

Made of protein parts and RNA, the complex contains a distinctively folded section of RNA called a pseudoknot. Found in many organisms, similar kinds of knots in other cell structures play key roles in promoting proper function.

With expertise in an advanced form of fluorescence microscopy that can measure structures one molecule at a time, UC Santa Cruz chemist Michael Stone and grad student Joseph Parks collaborated with computational modeling experts at Stanford to show a pseudoknot movement that occurred surprisingly far from telomerase's active site. "Whatever it's doing functionally, it must be acting indirectly," said Stone. The results are described in the journal RNA.

The bigger success of this study was combining single molecule measurements with computational modeling to find this pseudoknot movement, said Stone: "Telomerase is one of many protein-RNA complexes for which we don't know the structure. This is just the beginning."

Physics

Proton power

Proton radiation treatment can target solid tumors with less harm to surrounding tissue than X-ray radiation therapy.

Pretreatment planning requires a 3D map of “proton stopping power,” or how fast the proton loses energy and slows down as it passes through tissues before hitting the tumor. Those values are now estimated from images taken by X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanners, but a proton CT (pCT) scanner would make direct and more accurate measurements.

Now, UC Santa Cruz researchers, working with Loma Linda University Medical Center scientists, have a prototype pCT capable of completing a full scan of a human head-sized object in less than 10 minutes, said Robert Johnson, chair of the Physics Department and first author on a paper describing the machine, published in IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science.

Making a scan in a few minutes requires measuring a million individual protons per second, noted Johnson. With experience designing NASA’s Fermi–Gamma ray Space Telescope—plus leftover silicon-strip detectors from that project—Johnson helped overcome those technical challenges.

“We are now comparing simulated treatment plans [with the prototype] against those obtained by a new X-ray technique,” said Johnson. “If we’re successful it could really improve cancer treatments, which is the ultimate goal.”

Linguistics

Talking points

Technology started talking back when Siri was introduced. But "conversational agents" like Siri can't yet carry a conversation. While machine-learning systems can follow pre-scripted repertoires and adapt to user patterns, other elements of language—such as sarcasm—don't yet compute.

"To be effective, computers might need to acquire some social inferences," said Marilyn Walker, UC Santa Cruz computer science professor and leader of the Natural Language and Dialogue Systems Lab in the Baskin School of Engineering.

To create those capabilities, Walker mines online social sites to develop statistical algorithms that capture the flow of natural conversations. A team of her graduate students, the SlugBots, were picked to compete in Amazon's $2.5 million Alexa Prize Challenge to develop a "socialbot" that could turn the company's voice-controlled devices into chatterboxes.

Improving conversational algorithms also advances fundamental science, noted Pranav Anand, associate professor of linguistics. Working with Walker and UC Santa Cruz cognitive psychologists Jean Fox Tree and Steve Whittaker, he brings a "rich intuition about language" to develop these new algorithms. Ultimately Anand hopes their work will improve studies of language itself.

Linguistics

Talking points

Technology started talking back when Siri was introduced. But "conversational agents" like Siri can't yet carry a conversation. While machine-learning systems can follow pre-scripted repertoires and adapt to user patterns, other elements of language—such as sarcasm—don't yet compute.

"To be effective, computers might need to acquire some social inferences," said Marilyn Walker, UC Santa Cruz computer science professor and leader of the Natural Language and Dialogue Systems Lab in the Baskin School of Engineering.

To create those capabilities, Walker mines online social sites to develop statistical algorithms that capture the flow of natural conversations. A team of her graduate students, the SlugBots, were picked to compete in Amazon's $2.5 million Alexa Prize Challenge to develop a "socialbot" that could turn the company's voice-controlled devices into chatterboxes.

Improving conversational algorithms also advances fundamental science, noted Pranav Anand, associate professor of linguistics. Working with Walker and UC Santa Cruz cognitive psychologists Jean Fox Tree and Steve Whittaker, he brings a "rich intuition about language" to develop these new algorithms. Ultimately Anand hopes their work will improve studies of language itself.

Rachel Carson College

Peregrine proof

Glenn Stewart's Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group (SCPBRG) shepherded peregrine falcon recovery efforts from almost uncountably low populations in the '70s to removal from the federal list of endangered species in 1999 and—now—more than 50 breeding pairs in the Bay Area alone.

A network of conservation biologists and raptor enthusiasts boosted falcon numbers by collecting and hatching thin-shelled wild eggs, then pioneering methods for captive breeding and releasing the young. Nest cameras brought the population recovery story to a public audience, including that of "Clara," who raised four generations, and counting, on San Jose City Hall.

Unlike the 10,000 kilometer migrations of Arctic populations, Stewart's studies showed that Central California peregrines stick around. They follow the food, he said, nesting anywhere from Mt. Diablo to the smokestacks in Moss Landing.

Now retired from the SCPBRG, Stewart continues his research—and bands 3-week olds each spring. And, as a Rachel Carson College lecturer, he passes on the peregrines' success story. "We figured out how to cover the Earth with peregrines again," said Stewart." They are proof that conservation works."

Feminist Studies

Soils, war, life

Putumayo is located in the Andean-Amazonian foothills of southern Colombia. An extremely biodiverse region, it was also an epicenter of the U.S.–Colombia War on Drugs which, until recently, included aerial spraying of illicit coca crops.

When UC Santa Cruz cultural anthropologist Kristina Lyons began her fieldwork in Putumayo, she intended to research the public health and environmental consequences of the herbicide, glyphosate, that rained down from the sky.

Instead, after almost twelve years working with small farmers, soil scientists, state officials, and others, Lyons ended up following the practices that make life possible in a criminalized and poisoned ecology. "The farmers I met pushed me to transform my research questions, and to think about how life is being cultivated in the midst of war," she said.

Lyons' work, "Decomposition as Life Politics: Soils, Selva, and Small Farmers under the Gun of the U.S.–Colombia War on Drugs," was published in Cultural Anthropology and garnered the Junior Scholar Award from the Anthropology and Environment Society of the American Anthropological Association.

In post-conflict Colombia, after a peace agreement between leftist guerrillas and the government, Lyons continues to examine the complexities of science, nature, and justice.

Sociology

Asymmetrical lines

Informed consent for medical research participants didn't exist in 1951 when researchers took the cancerous cervical cells of Henrietta Lacks, a poor African American woman, and developed "HeLa" cell cultures for worldwide study.

By 2013, when scientists sequenced—and published—Lacks' genome from those cells without the family's permission, it spotlighted ethics, race, gender, and justice in biomedical research. Further, the National Institutes of Health director described Lacks as a matriarch for her contribution to science; an irony that didn't escape many, including James Doucet-Battle, a UC Santa Cruz medical anthropologist.

"Matriarchal societies are those in which women wield control over political and economic resources," said Doucet-Battle. "For Henrietta Lacks, and historically for African American women, that's not quite the case."

With Henrietta Lacks as a starting point, Doucet-Battle examined the social contract between society and government in his paper, "Bioethical Matriarchy: Race, Gender, and the Gift in Genomic Research," published in Catalyst.

"It's about answering whether there's a possibility of an ideal democratic form of citizenship, in which the obligations to give and receive are based not on sacrificial forms of exchange, but on egalitarian forms of exchange," he said.

Mollecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology

Supporting role

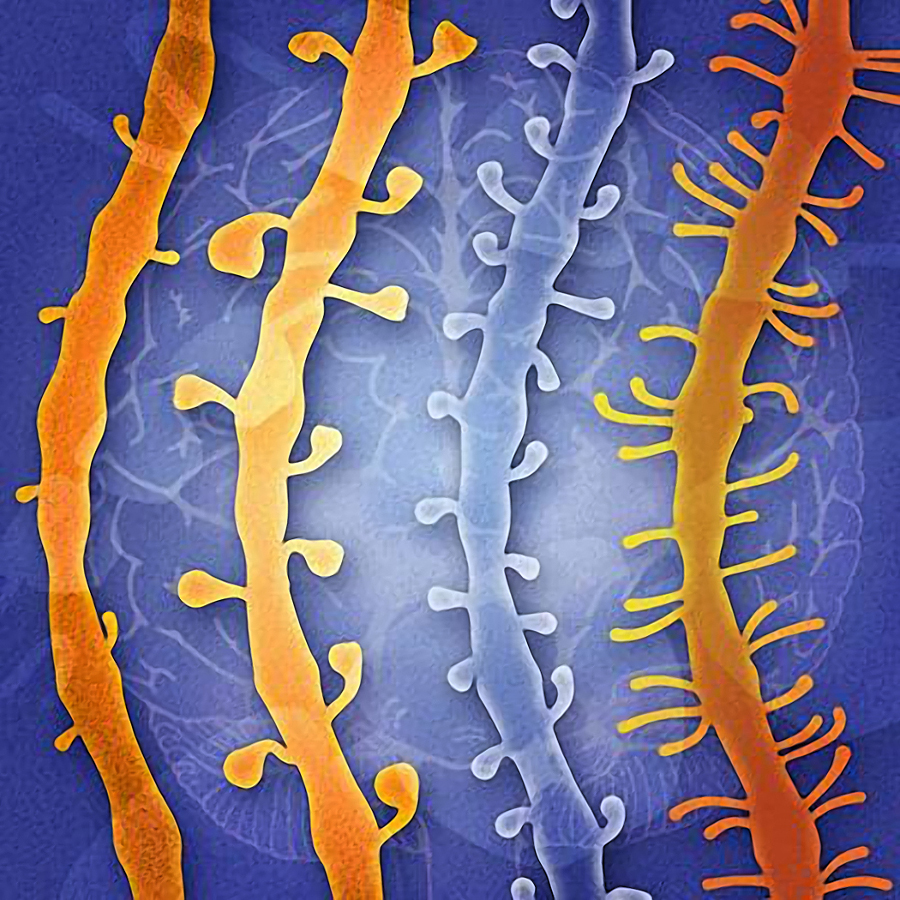

During development and learning, neurons in the brain grow small protrusions along branching dendrites—the dendritic spines—to boost cell-to-cell connectivity.

This process may be modulated by neuronal supporting cells, called astrocytes, more than previously thought according to new research by Yi Zuo, professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology. The study was published in Biological Psychiatry.

Zuo discovered the astrocytes' contribution by first studying mice with Fragile X syndrome, in which a lack of Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) leads to too many dendritic spines and impaired motor skills.

While neurons and astrocytes both express the FMRP protein, the neurons have 10 times as much, noted Zuo. So, she was surprised to find that selectively eliminating FMRP in astrocytes—while maintaining neurons' protein expression—still led to symptoms of Fragile X. "Even though astrocytes express very little of this protein, they seem to be contributing to the disease," said Zuo.

Next, Zuo's team seeks changes in astrocytes that may be important for synaptic transmission. She also wants to learn more about the role of astrocytes in aging.

"Neurons are still very important," said Zuo, "but we should pay more attention to astrocytes."

Anthropology

DNA directions

For example, reconstructing the genomes of 92 pre-Columbian individuals enabled Fehren-Schmitz and his colleagues to track the migration of people, once isolated on the Beringian land bridge for thousands of years, into the Americas starting around 16,000 years ago. That early isolation period created a unique pattern of genetic diversity, traceable as those populations moved southward to Chile, explained Fehren-Schmitz, an author on the study published in Science Advances.

Among those ancient samples, Fehren-Schmitz also found DNA markers no longer seen in modern data sets, suggesting a high extinction rate of Native American people around the time of first European contact. "Our high-resolution data allowed us to verify the historic record," he said.

DNA markers in another study showed that adaptation to high altitudes existed before people got to the Andes, a trait that allowed populations to persist there.

Now the UC Santa Cruz Paleogenomics Lab is expanding and, along with it, Fehren-Schmitz's research plans. "How far can the interactions between biology and culture shape diversity in populations?" he wants to know; "not just in ancient peoples, but in contemporary populations and in how our future development will look."

Sociology

Sound solutions

Informed consent for medical research participants didn't exist in 1951 when researchers took the cancerous cervical cells of Henrietta Lacks, a poor African American woman, and developed "HeLa" cell cultures for worldwide study.

By 2013, when scientists sequenced—and published—Lacks' genome from those cells without the family's permission, it spotlighted ethics, race, gender, and justice in biomedical research. Further, the National Institutes of Health director described Lacks as a matriarch for her contribution to science; an irony that didn't escape many, including James Doucet-Battle, a UC Santa Cruz medical anthropologist.

"Matriarchal societies are those in which women wield control over political and economic resources," said Doucet-Battle. "For Henrietta Lacks, and historically for African American women, that's not quite the case."

With Henrietta Lacks as a starting point, Doucet-Battle examined the social contract between society and government in his paper, "Bioethical Matriarchy: Race, Gender, and the Gift in Genomic Research," published in Catalyst.

"It's about answering whether there's a possibility of an ideal democratic form of citizenship, in which the obligations to give and receive are based not on sacrificial forms of exchange, but on egalitarian forms of exchange," he said.