Body work

A mathematical quest

Ever since Newton precisely predicted the orbits of two celestial bodies governed by gravity, the quest began for a solution to a three-body problem. It wasn't something that UC Santa Cruz mathematician Richard Montgomery ever planned to tackle, once saying: "Celestial mechanics is the land of old, famous, long-dead men; a world of very hard problems."

This "N-body problem" arose after Newton posed a system of differential equations whose solutions described how some arbitrary number, "N,'' of gravitating masses can move. His solution for the two-body problem forms the foundation for much of physics and astronomy. Yet a solution for three bodies in orbit eluded even Newton.

In the ensuing centuries only five families of explicit formulae (applicable only under specific sets of conditions) have been found. Furthermore, French polymath Poincaré proved the three-body problem can never be "solved'' with a single closed-form formula that describes all solutions. But the quest didn't end there.

"As is almost always the case in mathematics, impossibility proofs open up much vaster fields of study than those which they close," said Montgomery, noting that Poincaré's proof led to "chaotic dynamics" and other modern mathematics.

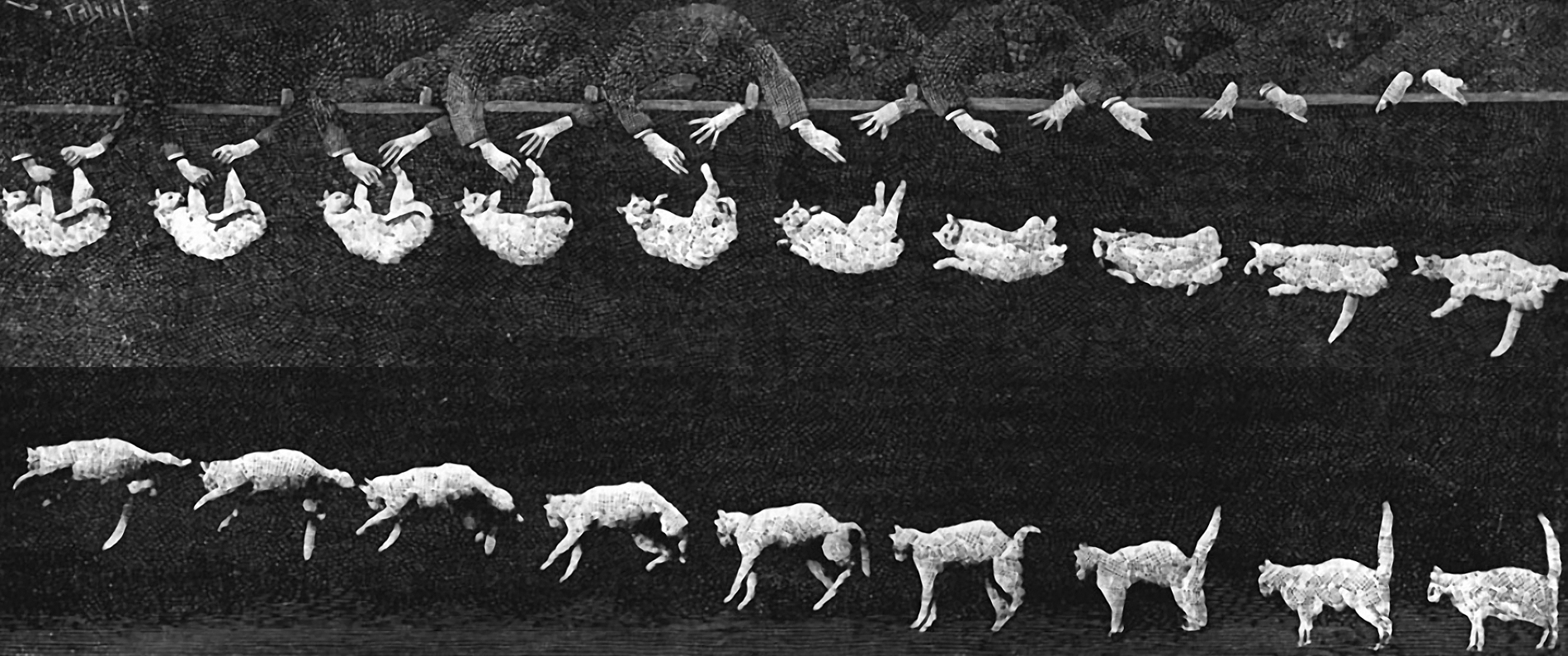

By 1993, Montgomery solved the classic "falling cat problem," showing how cats could change their shape to land on their feet despite the fact that their angular momentum must remain zero throughout the fall. His closed-form solution simplified the cat's body to three points of mass—echoing the three-body problem. With that, Montgomery entered the fray.

In 2000, collaborating with French mathematician Alain Chenciner, Montgomery rediscovered the "figure-eight'' solution, in which three equal masses chase each other around an 8-shape. Their work inspired numerous other choreographies (and a science fiction novel), but none offered explicit closed-form formulae.

For the next 17 years, Montgomery grappled with this: As the three masses move, they occasionally line up, all three on a single line with one between the other two; an eclipse. Three kinds of eclipses exist, depending on which mass is in the middle. If the bodies are "Red," "White," and "Blue," the eclipses can be "R," "W," or "B." (In the figure-8, RWBRWB repeats infinitely.) But the overarching question was: Given any sequence of eclipses, such as RWBRWBRRWWWRBR, is there a solution to the three-body problem which realizes this sequence?

"Yes," said Montgomery, but getting that answer required different mathematical methods from those that revealed the figure-8 solution. That new approach came from working with mathematician Richard Moeckel, at the University of Minnesota, and his chaotic dynamics theories. Their solution, derived in 2014, also allowed for resting points in each orbit—though real stars never stop moving. But their answer requires close to equally sized masses and a small angular momentum.

What happens when the angular momentum, like that of the falling cat, is actually zero? No one yet knows. "But, in pursuing really good problems we develop new methods," said Montgomery, "and mathematics becomes as much art as science."