Tracking Toxic Tides

Ocean sciences professor forecasts toxic algae events

When a giant algal bloom turned Pacific coastal waters poisonous from Santa Barbara to Alaska in May 2015, Raphael Kudela was ready.

His team from the Biological and Satellite Oceanography Laboratory not only stepped up their routine ocean water sampling, they also worked with collaborators to deploy more sophisticated instruments—including an underwater molecular biology lab, affectionately called “lab in a can,” to measure toxin levels and types of algae, a remote-controlled glider to gather information from different water depths, and wave-powered “wire walkers” loaded with recording devices.

A professor of ocean sciences, Kudela studies and tracks harmful algal blooms (HABs). He uses a variety of tools and collaborations that make it faster and easier to detect problems and work with health and fisheries agencies.

“From a scientific perspective, we were happy to see the bloom because we could collect the data we need to actually predict what’s going on,” said Kudela.

That’s the goal—to predict when and where toxic events are likely to emerge and, in turn, inform policy and management decisions that can minimize the impacts. Kudela’s lab and an alliance of researchers and public agencies are making rapid progress after almost a decade of building upon local trials.

The sooner the better. HABs are responsible for progressively higher economic losses, health threats, and damage to ocean and freshwater life. The 2015 West Coast bloom closed the commercial and recreational Dungeness crab fishery for the first time ever in Northern California, and temporarily took anchovies and rock crab from several California counties off the menu.

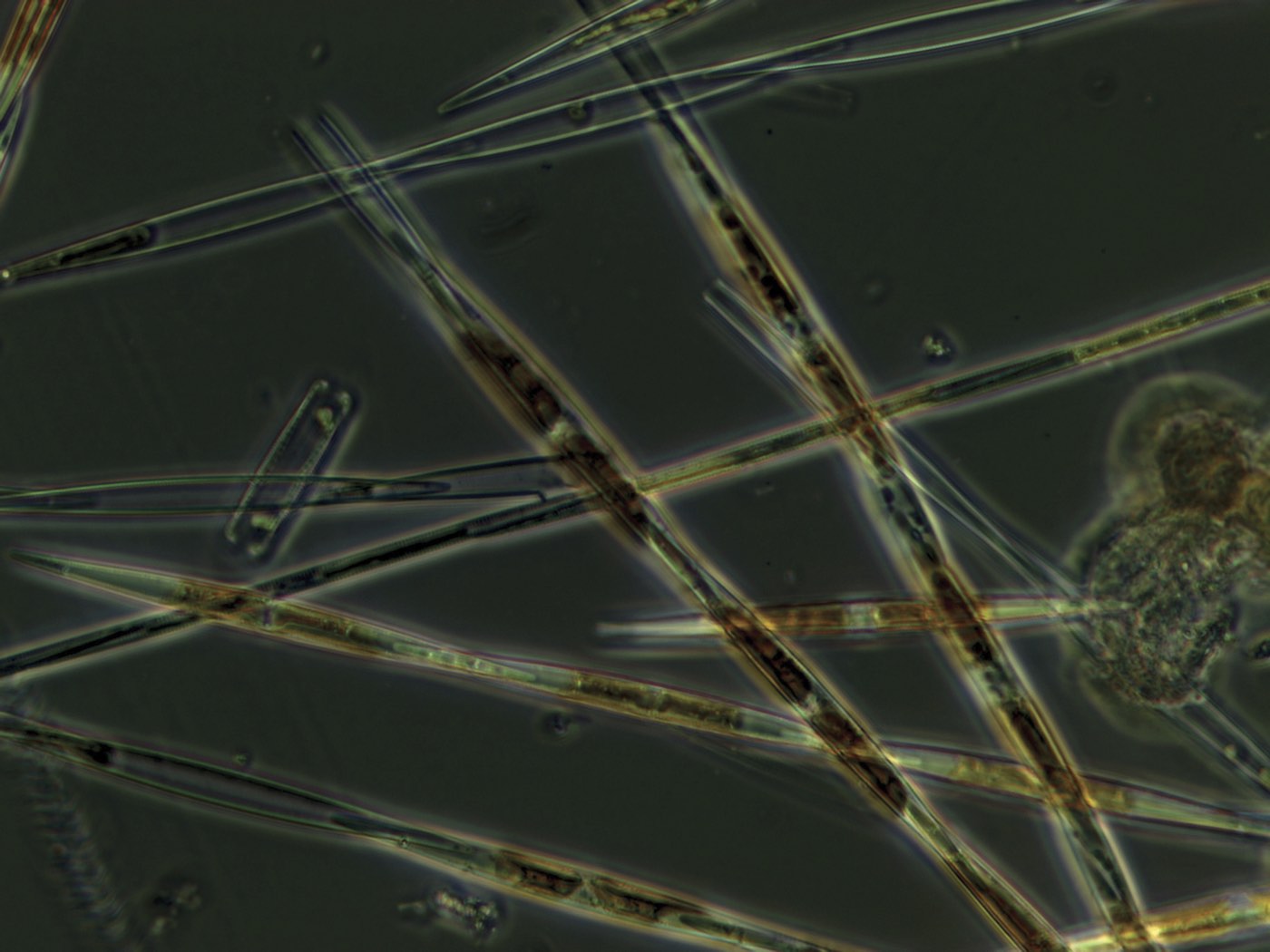

The troublemaker? A neurotoxin named domoic acid, produced by the blooming microalgae Pseudo-nitzschia. As well as the fisheries, the toxin also afflicted sea lions, seabirds, and other marine animals causing amnesia, seizures, comas, and death.

Many species of microalgae produce different toxins that attack the liver or nervous system and cause illnesses, including paralytic shellfish poisoning and diarrhetic shellfish poisoning. Even nontoxic blooms can be harmful by clogging fish gills or draining all the oxygen out of the area as they decompose, killing a variety of aquatic creatures.

The microalgae, also called phytoplankton, are dynamos: In bloom conditions, their numbers surge so quickly that some species color miles of ocean red and whole lakes bright green. As photosynthesizers, they remove carbon dioxide from the water and vent oxygen into the atmosphere—up to half the oxygen we breathe comes from phytoplankton.

At the bidding of currents and winds, thousands of phytoplankton species sail the oceans, their single-celled bodies turning sunlight into food for everything from the smallest shrimp to the widest whales. Which means the toxins produced by HABs percolate through the food chain.

As the world heats up, and oceans and freshwater along with it, the duration and intensity of HABs will escalate, posing increasing risks to aquatic and human health, fisheries, and drinking water.

“After years of seeing harmful blooms, that naturally led us to wonder ‘is there something we can do?’” Kudela asked.

He has answered “yes” in many ways.

Working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and others, Kudela’s lab harnessed research and data to create a demonstration forecasting model.

Now active on the Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System, the demo draws from satellite data on algal concentrations, real-time observations of biological activity and water conditions, calculations of circulation patterns, and statistical programs for prediction.

Tracking toxic tides

Maps based on current and future conditions show the probabilities of finding Pseudo-nitzschia blooms and domoic acid events along the California coastline. (For unknown but hotly investigated reasons, Pseudo-nitzschia doesn’t always make the toxin.)

“A complete predictive model will be a valuable resource for researchers and ocean users,” said David Caron, professor of biological sciences at the University of Southern California who contributes data for the model.

The maps currently advise: “Experimental Data—Use Cautiously.” But the information is already being used by marine mammal rescue groups to get a sense of how many sea lion strandings to expect in particular locales. Shellfish growers are beginning to pay attention, too; ultimately, insights from the maps should help them choose where and when to seed and harvest.

The model is also serving as a template for groups in Great Britain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. The latter two get at least 70 percent of their drinking water from desalination plants. Algal blooms obstruct plant filters; local HAB prediction could tell operators when to pull ocean water from deeper inlet pipes (phytoplankton live near the surface) or a different location.

“The research has gone almost all the way from a demo to a product that will be useful for policy, management, and the public,” Kudela said. The project, later to include Oregon and Washington, is scheduled to become part of NOAA’s National Weather Service and the National Ocean Service.

Looking for the big picture

Advances in science and technology have been crucial to building these predictive capabilities, and to analyzing the biology, chemistry, and physics of the tiny organisms and their watery world.

Satellites now play a major role in phytoplankton research. Kudela received a NASA grant for HAB forecasting, and his lab uses the space agency’s satellite data in a variety of ways.

“With remote sensing you can see the big picture, and take that information and move it into models so you can make predictions,” he said.

High-resolution satellites can precisely measure the amount of biomass, light scattering, chlorophyll, and other pigments in the water. In a 2015 journal article, Kudela’s team showed they could use this information to distinguish toxic and nontoxic freshwater algae blooms from space. Further, Kudela can specifically track Pseudo-nitzschia by the “signature” it presents to a satellite.

Freshwater HABs are also a concern. Now reported in every state, they can cause health problems ranging from allergic skin reactions to liver failure or sudden death, in both people and pets. Studies show that chronic exposure can even increase risk of cancer. One freshwater toxin, microcystin, sickens Monterey Bay sea otters when blooms flow to the ocean from inland water sources. It has also contaminated the drinking water of more than half a million people in the United States.

Soon, a newly launched satellite may be able to scan smaller bodies of water for telltale signs of dangerous blooms. Kudela’s lab is vetting the satellite to make sure the data it picks up from space matches the samples researchers take from the water.

In Santa Cruz, they verified that the satellite could “see” with 10-meter resolution exactly where a freshwater HAB and a saltwater HAB, each producing a different toxin, were mixing in the San Lorenzo River in the quarter-mile stretch between the ocean and the train-trestle bridge.

Kudela then advised city officials to let the peaking algal blooms subside before removing a sand berm and letting the river flow to the ocean. Otherwise, the algae could have seeded new blooms in coastal waters.

Satellites aren’t the only practical way to observe and gather evidence for decision making. In a pilot project with the California Department of Public Health, Kudela’s lab developed inexpensive, rapid test kits that can be used in the field to check for shellfish toxins. Each kit probes for a different toxin, with a simple stick showing a plus or minus sign, just like a pregnancy test.

Another Kudela-cultivated method that might prove helpful and more economical than traditional assays works by extracting pigments from a water sample to determine its algal constituents. His lab is teaming up with the U.S. Geological Survey to learn whether this technique can divulge enough information to assess the health of the San Francisco Bay.

“The impact of climate change is a huge open question,” Kudela said.

In the short term, higher water temperatures will provoke more HABs, he explained. The 2015–16 El Niño weather system brought both warmer waters and winter storms that washed chemicals from fertilizers, pesticides, and even leaking septic systems into the ocean, where they acted as algal nutrients and increased the chances for a massive spring bloom on the Central Coast for a third year in a row.

In the long term, climate disruption will alter water temperature, precipitation, wind, nutrient availability, light intensity, and ocean acidification. All of which will change—in still speculated-upon ways—the activity and community composition of phytoplankton. For instance, the day-to-day productivity of nonbloom phytoplankton might drop, jeopardizing the aquatic food chain and increasing carbon dioxide levels in the ocean and atmosphere.

Preventing HABs while protecting active—but not hyperactive—microalgae might be possible one day. In the meantime, Kudela said, “monitoring, early warnings, and well-coordinated research is clearly an important investment in food and water safety and in our marine and freshwater environments.”