Total recall

Do digital footprints alter our relationship to the past?

There is widespread concern that at-our-fingertips accessibility to all the information on the Internet has eroded our memories and thought processes. However there’s no denying that it’s also made life a good deal easier. Anyone under the age of 25 has likely never had to summon up a friend’s telephone number from memory or give someone turn-by-turn directions to a party. And not all scholars share this dim view of the changes digital technology has wrought.

“There’s a bunch of ways that technology is absolutely transforming all of these human [thought and social] processes,” said Steve Whittaker, UC Santa Cruz professor of psychology, who specializes in the study of human computer interaction, the intersection of psychology and computer science. “I’m very interested in trying to document and understand those effects,” he said. “But I’m also very interested in how we might better design technologies to help us with things that we have problems with.”

One of the problems stems from the sheer amount of digital “stuff” we accumulate. The average person produces six newspapers’ worth of information per day—a nearly 200-fold increase compared to two decades ago, according to Martin Hilbert, professor of communication at UC Davis. This figure encompasses digital documents, emails, blog posts, photos, audio/video, and messages on social media.

In Whittaker’s lab, a principal research theme concerns the ways people organize their digital archives, and how the structure (or lack thereof) affects their ability to retrieve a specific piece of information when needed. “A lot of this stuff about organizing file systems, what you’re doing is basically trying to guess what the information needs of your future self will be. And we’re not very good at that.”

Search patterns

Having worked in the tech sector for nine years, Whittaker holds more than 30 patents for communications and user interfaces. He noted that despite improvements in search—and the apparent advantage, in terms of flexibility, of using keywords to locate a computer file—most people use search only as a last resort.

It’s no accident that graphical user interface design draws on analogies to the physical world: the icon for a text document looks like a sheet of paper, the icon for a folder looks like a manila file folder, and so on. Whittaker hypothesized that when we navigate these virtual representations, it engages parts of our “animal brain” involved in locating an object in physical space.

“I don’t want to judge squirrels, but they’re probably not the most intelligent,” he said wryly, “Yet they seem to be pretty good at re-finding things that they’ve hidden.”

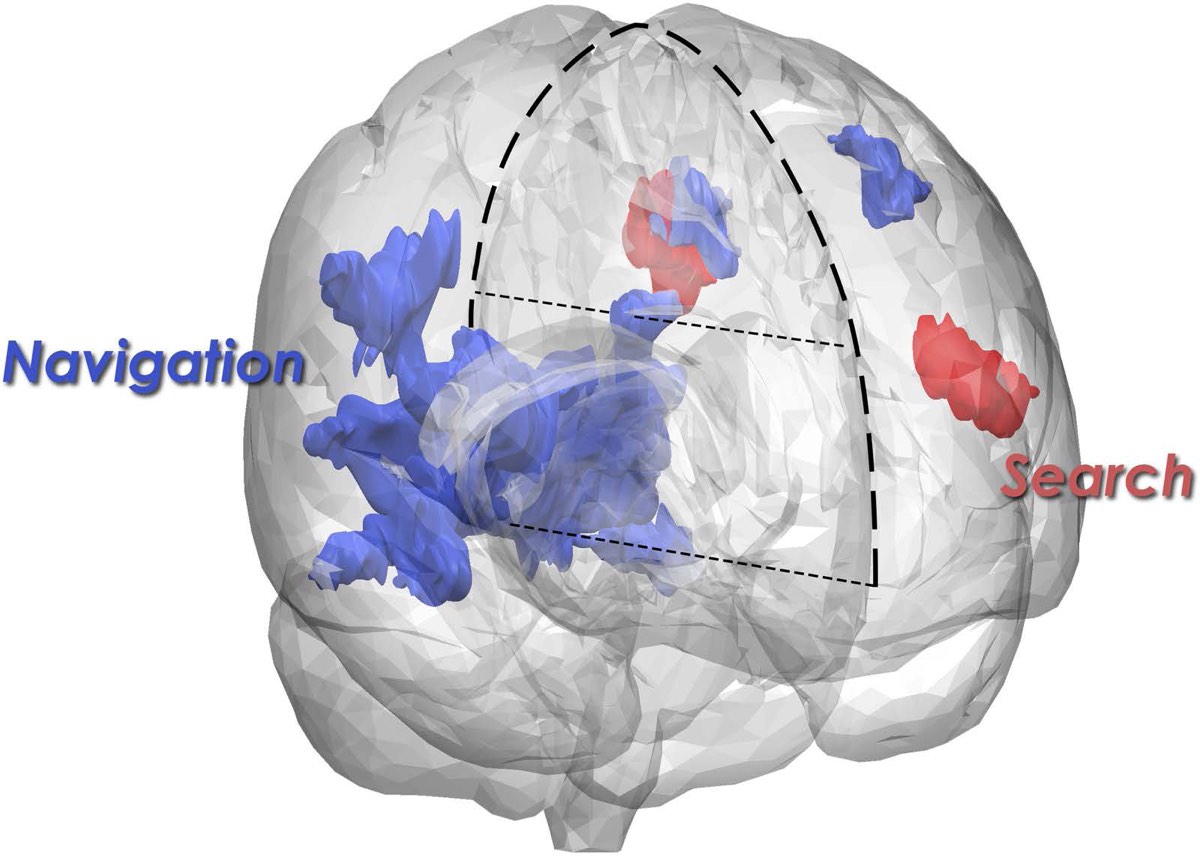

Whittaker collaborated with colleagues at England’s University of Sheffield and Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv on a study that used functional MRI to compare activity in the brains of 17 students while they retrieved target files from their own laptops, either by navigation or by search. The success rate didn’t differ significantly between the two methods, but the patterns of brain activity were distinct.

When you search, Whittaker explained, you have to think about characteristics of the target document—when it was created, the type of file it is, words it contains, the file name—and intuit what query terms will lead you to it. In contrast, navigation is a lower- level thought process that doesn’t compete for resources with higher faculties. Whittaker concluded that, given the choice, people usually opt to use the less cognitively demanding, if more primitive, method.

Character counts

Of course, the degree to which people attempt to organize their digital information varies. For instance, some individuals create deeply nested hierarchies, with subfolders containing relatively few items that are closely related, while others create a handful of superficial folders into which they lump a larger number of items that are related only loosely. And then there are those who just leave everything exposed on their desktop with no attempt at organization. While many factors likely account for these differences, Whittaker demonstrated that some of these tendencies can be reliably linked to personality traits.

In academic circles, “personality” refers to the way a person consistently thinks, feels, and behaves. Psychologists have identified five major dimensions of personality—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Research has shown that for physical spaces, such as a dorm room or an office, certain cues can reliably predict these traits; for example, the variety of media the inhabitant owns is an indication of greater openness to experience.

Whittaker and his colleagues wrote a program that analyzes where all the personal files on an individual’s computer are stored and how they’re structured. The program strips the folder and file names that might reveal their contents, but shows where in the file hierarchy they’re located (e.g., on the Desktop, or in a subfolder within Documents).

The research team found that relationships were somewhat different for Mac and PC users, but for both, the personality trait of conscientiousness was related to active organization in Documents and Desktop, reflected in the average number of files per folder.

However, the relationship only held when the overall number of files was low. A more unexpected finding, said Whittaker, was that individuals who scored high in neuroticism tended to have a larger number of files on their Desktops, particularly as their workloads increased. He speculated this might be due to anxiety over forgetting something that needs to be acted on.

Urging caution over reading too much into the results, Whittaker stressed: “These are not amazingly strong effects, but they’re tendencies.” Still, he mused, such insights could be helpful in developing new digital-information-management tools that take personality into account.

Past perfect

Another major theme in Whittaker’s research is the impact of digital memory on people’s emotional well-being. People who routinely use social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to share aspects of what they’re doing, thinking, and feeling from moment to moment are creating rich and enduring—albeit somewhat skewed toward positive self-projection—records of the minutiae of their day-to-day lives.

“We’re quite interested in whether that’s changing our relationship to the past,” he said.

Unaided by technology, our recollections of our own histories are not entirely accurate. Human memory positively edits the past via a couple of well-studied phenomena, explained Whittaker. For instance, a vacation may start with long security lines at the airport, getting wedged into the middle seat on the plane, and lost luggage. At the time, these negative experiences seem very salient to the traveler.

After the trip, these incidents may not be mentioned, or even remembered. Psychologists call that positivity bias; people recall two to three times as many positive events as negative ones. And a year later, that hapless vacationer likely won’t remember that the bad stuff happened at all, thanks to the tendency of negative emotions to subside more quickly than positive ones—the so-called fading affect bias.

But what happens, Whittaker wondered, when you go back and read an unimpeachable account (your own!) of the raw emotions—pain, anger, loss—you felt at the time you were going through something difficult? Does it interfere with the mellowing effect of time? The answer, happily, seems to be no.

Self-determination

His team designed a smartphone application that allows users to capture what they’re doing, thinking, and feeling throughout each day by writing a brief description of an event—including photos, audio, or video if they choose—and rating their emotional reaction on a scale of 1 to 9 (negative to positive). Essentially posting private “status updates” to themselves.

In developing the app, Whittaker randomly assigned 33 study participants to receive one of two versions. In one, the “recorders” were asked to complete at least three entries per day. They could view and edit their posts only until the end of the day, after which point the posts were hidden. In the alternate version, in addition to logging three new events each day, “reflectors” were presented with three previous entries and asked to write down their thoughts and rate their current feelings about the past events.

At the beginning of the study, all participants were given a battery of psychological surveys designed to gauge well-being. The tests were repeated after a month, during which time app users recorded mundane events such as drinking a cup of coffee, major events such as interviewing for a job, negative events such as quarreling with a loved one, and positive events such as enjoying a social outing. Users of both versions of the app showed improved well-being scores with no significant difference between the two.

Both improved over controls who reflected about emotionally neutral events.

“Crudely expressed,” Whittaker said, “people get happier just through that experience of recording or thinking through their past experiences.” That finding is in line with research by others in the field of positive psychology who have shown that recording and reminiscing can have health and social benefits. However, technology-mediated reflection may provide additional benefits beyond those of simple recording. It can help people see patterns in their emotional responses to situations and alter their behavior, or gain perspective on negative experiences and reframe them as “redemption narratives” of resilience.

The current version of the Echo app, available for Android phones, is intended for people who are basically mentally healthy and just want to improve their well-being. It doesn’t direct users to analyze past events in a structured way. But, Whittaker said, future versions could incorporate prompts based on techniques from cognitive behavioral therapy to help people work through negative feelings by approaching them from a problem-solving stance.

“What’s interesting to us from the point of view of designing these types of systems,” remarked Whittaker, “is that people don’t know what’s good for ‘em. We say to people: ‘What kind of information would you like us to present?’ And they say ‘Oh, just keep it positive.’ But in order to get some of the benefits of these applications, it’s good to have negative stuff.

We don’t know our futures and these technologies are giving us insights into how little we know about what’s going to happen to us,” Whittaker added.