Following the law

Chronicling politics, religion, and law from Africa to California

When peace returned to Sudan after more than two decades of civil war, Mark Fathi Massoud followed. After a long absence from his native country, the UC Santa Cruz professor of politics and legal studies spent a hot and dusty summer interviewing people about their encounters with law during those tumultuous years. He returned repeatedly during the next six years to question hundreds more. His goal was to uncover the way successive rulers exploited the law throughout the country’s troubled history. Ultimately, his investigations revealed how law survived in the thick of political chaos.

Massoud‘s research documents the interaction between law and society. Scholars in his field study how citizens use courts and the legal system to further political agendas. Most of that work has focused on institutionalized settings in developing countries. In the United States, for example, Brown v. Board of Education pushed forward the goals of progressives who considered school segregation morally wrong. More recently, gay activists won the right to marry via a series of court decisions.

A few intrepid scholars have broadened this scope, studying women’s rights in the Middle East, environmental rights in China, or gay rights in Asian countries. But they are the vanguard and—until Massoud—none had considered looking at laws and courts in the world’s most fragile states.

“I realized there’s a gap here,” said Massoud. “Do all these grand theories about law and society apply to a place like Sudan?”

Expanding on that research, he’s now documenting the complex interplay of religion, law, and politics in places as disparate as war-torn African nations and his adopted home, in California.

Back to the beginning

When Massoud told colleagues he planned to write about the rule of law in Sudan, they joked to him that his book would be a short one. The country has only known ten years of democracy, scattered between lengthy dictatorships, since its release from British colonial rule six decades ago. Between 1983 and 2005, the country was wracked by war between powerful politicians in the country’s capital of Khartoum and forces in what is now known as South Sudan.

Accounts of the country’s southern and eastern regions are peppered with words like “lawless” and “chaos.” With such strife, Sudan has ranked at, or near, the top of the Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index (formerly known as the Failed States Index) for years. The Index tracks a dozen factors such as the number of refugees and internally displaced people, economic decline, and governmental legitimacy.

Massoud was drawn to understand the paradoxical role that law played in his war-torn homeland. His own family fled Sudan in the early 1980s, and he returned to study not just Sudan’s postcolonial history, but how the legal framework constructed during colonial times set the stage for post-independence laws. His collected observations became an award-winning book, Law’s Fragile State.

“Trained in the study of the law, his work reaches deep into other disciplines like political science, sociology, and anthropology in ways that are novel and thought provoking,” said Kent Eaton, UC Santa Cruz professor of politics.

Massoud examined Sudan’s rule of law during three political eras: colonial times, during the country’s post-colonial independent years from 1956 to 2005, and the transitional period between 2005 and 2011. Finally, in a move facilitated by peace treaties signed six years earlier, South Sudan seceded from Sudan in 2011.

Despite those upheavals, he found that law wasn’t absent from Sudan. In fact, it permeated the country even as a series of autocratic rulers sought to bolster their legitimacy and strengthen their power by manipulating the legal system.

In Sudan

For more than 50 years, from around the turn of the 20th century to Sudanese independence in 1956, colonial rule in Sudan was a joint operation between Egypt and Britain. In reality, power was retained mostly by the British, but they made room within the colonial legal system for Islamic laws and local customary laws for matters such as marriages and family disputes vis-à-vis a parallel court system run by local arbiters. They also provided courts where Sudanese could petition for exceptions or minor changes to the law involving issues such as adjustments to a family’s grain allocations or allowing a murder victim’s family to request a death sentence.

After independence, Sudan suffered through a series of shaky governments. Democratically elected governments were routinely toppled in a series of coups d’état. But Massoud noted that both the democratic governments and the dictatorial rulers used the law to push forward their political goals. When they could, democratic governments attempted to build new laws on the British colonial common law system. In turn, authoritarian governments sought to consolidate their hold on the country through legal maneuvering of Sudan’s system. For example, when dictator Jaafar Nimeiri neared the end of his regime in the early 1980s, he suddenly decreed that all Sudanese law would be based on shari’a (roughly translated as Islamic religious law).

As a counterbalance to government machinations, since 2005 an influx of aid groups—including United Nations agencies, the World Bank, and other human rights organizations—have sought to teach Sudanese people about their country’s laws and international laws. Massoud noted that international aid workers also often see the law as a way to promote equality among the citizens of developing countries.

However, human rights NGOs are not an unalloyed good in this conflict-ridden country. Despite noble goals, their abstract ideas about human rights may not take into account the particular ways that Sudanese authorities can stymie the rights of their citizens. Trainings for local people may help them understand human rights conceptually, but it may not help them apply those ideas to their own predicaments.

Massoud also noted that one unintended consequence of these trainings is that authoritarian regimes may allow NGOs to operate in their country to create a false legitimacy among the Sudanese and international powers. This further cements dictatorial control, despite ongoing oppression of citizens’ rights. For example, President Omar al-Bashir, indicted by the International Criminal Court for his part in atrocities in Darfur, allows NGOs to operate in Sudan, but only within limits set by his government.

“When those boundaries are transgressed, these organizations face persecution from local or national authorities,” Massoud said. Sudanese government authorities routinely thwart court petitions they see as problematic, and human rights advocates are regularly jailed or, in the case of foreign aid workers, ejected from the country.

Massoud argues that none of these—neither the colonial rulers, the authoritarian regimes, nor the NGOs—are monoliths. Therefore, their impact cannot be simplified as either good or bad. Even within the worst of dictatorships that exert great power and abrogate citizens’ rights, there are individuals—usually at lower- to mid-levels of government—that attempt to make decisions that promote human rights and democratic representation, said Massoud, thereby muddying the divide between authoritarian and democratic governments.

This work in Sudan formed the basis for both Massoud’s doctoral dissertation at UC Berkeley and his first book. Massoud’s thesis adviser, Malcolm Feeley, made the book required reading for his courses at UC Berkeley and said he expects it to become a critical text about law in unstable countries. Among other awards, Massoud earned a Guggenheim fellowship for his contribution to the study of law, and most recently has been named an Andrew Carnegie Fellow.

Exploring uncharted territory

“An important, new, understudied issue arose and Mark helped define the nature and scope of it,” said Feeley of the relatively new study of the rule of law in middle- and low-income countries. “Of all the people who have worked in [this area], his work is not only among the very best, he has the most extreme case—in the instance of Sudan—to explore law and courts. And what he reports is a tragedy.”

Between 2005 and 2011, Massoud conducted more than 200 interviews in Sudan for his studies. He spoke to clerks and judges, government employees, humanitarian aid workers, and civil society activists. The interviews with locals were often fluid, consisting of a series of open-ended questions about the law, human rights, and what role they played in Sudanese life. He asked lawyers and judges about the details of the Sudanese legal system and he asked civil activists what motivated them to undertake the risks they did for their work.

But arranging those conversations wasn’t easy.

“Professor Massoud has faced and overcome tremendous logistical and cultural challenges in his research,” said Eaton, “which combined formal interviews with high-level political and judicial elites in Khartoum and Juba on the one hand, with ethnographic insights derived from extensive conversations with individuals in camps for the internally displaced on the other.”

Relying on his early exposure to Arabic as a child and language studies while he was a law student, Massoud spoke and read Arabic well enough to navigate the country and parse written legal documents. Weaving through the cultural issues took more effort, since most of his formative years were spent abroad.

One inescapable challenge of working in Sudan was what outsiders have called the country’s “IBM” mentality. It’s not a reference to the tech giant; the phrase dates back to colonial times and refers instead to “Inshallah, Bukra, Ma’elesh.” When Massoud requested meetings with potential sources, he often heard, “Inshallah (if God wills),” or “Bukra (tomorrow, in a loose sense), 11 a.m.” But the interview often didn’t happen. The interviewee would tell him, after the missed appointment, “Ma’elesh!” (never mind, forgive me).

Over the years Massoud spent researching in Sudan, he came to appreciate the mindset. “You’re an academic, and you’re trying to get your work done, so Inshallah Bukra Ma’elesh doesn’t work because you need answers now, now, now,” said Massoud. “But also, it’s a little liberating because you can slow down a little bit.”

More unnerving were the risks for locals participating in Massoud’s research. Speaking frankly about the government in Sudan can be a perilous prospect. Al-Bashir’s authoritarian regime routinely apprehends activists and others it sees as dangers to the country’s stability. So Massoud had to work to get his sources to trust him. At least one of his interviewees accused him of working for the Central Intelligence Agency.But Massoud persevered, doggedly reaching out, again and again, to make the contacts necessary for his research.

As a result, Massoud is fiercely protective of his sources’ confidentiality, revealing scant personal information about them. As an added precaution, he translated all the interviews from Arabic himself, and then transcribed them, too.

Along with gathering information about the technical aspects of Sudanese law, Massoud also documented the painful realities of life in Sudan, especially among the poor who attended the legal training workshops held by NGOs. He learned of people who had been imprisoned but didn’t know what their crime was. Massoud described how internally displaced people fleeing civil war told him about government soldiers’ disregard for the rights of civilians in conflict regions and countless instances of outright violence against them. Lawyers he spoke with described the lengths to which the government would go, infiltrating Sudanese human rights groups or disbanding them entirely, if they became big enough threats.

“There’s a story there and I’ve been trusted with it,” he said, of the information gathered from his interviewees. “When someone opens up, I’m tasked with holding this precious thing, of what is in someone’s heart, what is in someone’s mind.”

Among his projects in Sudan—and his recent research on Islamic law in Somalia and California—Massoud conducted more than 400 interviews. “It’s a lot of stories, and sometimes a lot of stories of suffering,” he said.

Inspecting history

In addition to the in-depth interviews and ethnographic studies, Massoud reviewed upwards of 4,000 pages of archived documents and records in three different countries. He reviewed documents in half-a-dozen libraries in Sudan and hunted down files in the historical archives of Sudan’s former colonial masters, Egypt and Britain.

Next Massoud looked for recurring words that pointed to themes in the interviews and legal documents. His methodological approach involved categorizing parts of the transcribed interviews using hundreds of codes and subcodes, such as “the impact of colonialism on religion” or “courtroom procedures.” He then compared these codes across his interviews and field notes.

To understand the information he gathered, Massoud borrowed an approach from the field of comparative politics, which seeks to understand politics by comparing, for example, the forms of legislature or foreign policy in different countries. Instead of looking at different countries, though, Massoud compared political regimes during different eras of Sudan’s history.

“History is very important to me,” said Massoud. “Not just the history that shapes the present, but the history that shapes history. In my work, I’ve thought comparatively across historical contexts within the same national context.”

Sudan’s neighbors

One of the themes that emerged from Massoud’s work on the Sudanese rule of law was how authoritarian leaders used shari’a to give their governments a veneer of religious legitimacy.

Many Westerners are unfamiliar with shari’a, which goes beyond codified law and provides a moral framework for the everyday decisions of Muslims, noted Massoud. It forms the foundation of behaviors such as how to treat others, how to settle disputes between neighbors, and how to make difficult ethical choices such as whether or not to vote for controversial propositions that extend marriage rights to gay couples.

Like Sudan, the governments of Somalia and the self-declared, independent Somaliland also rely on shari’a. These countries share many of the same political troubles, too. Somalia frequently tops the Fragile States Index and has been subjected to civil strife for many years. Border disputes between breakaway states are flash points for violence, and civilians live with the threat of displacement in each country.

For Massoud, these similarities made studying the legal systems of Somalia—and how shari’a is interpreted in a setting like Somaliland—a natural extension of his work in Sudan. Since 2013, he’s done fieldwork in Somaliland, located in the northern reaches of Somalia.

In many parts of the world, including Somalia, he noted, some people justify the brutal treatment of women or minorities using shari’a. But Massoud stressed that the functions of Islamic law depend on context. “It depends on where you are, what time period you’re talking about, and which political leader is looking to justify policies, and how,” he said.

Rulings made by courts about the obligations and rights of women differ by country. For example, some Muslim-majority countries, including Sudan, allow women to be judges. Yet, in Saudi Arabia, women are barred from driving cars and cannot leave the country without written permission from their wali (male guardian).

However, Morocco, another country where shari’a dictates national law, has made strides toward gender equality. In the last decade, the country revised its family law code to provide more protections for women. These included more equitable rules for inheritance (previously, female heirs received half of what male heirs received), less strict rules for divorces initiated by women, and an older minimum marriage age for women. And four years ago, a slate of amendments to Morocco’s constitution included some that required greater gender equality. Such examples highlight how interpretations of shari’a change over time.

Like the law, Massoud noted, religion can also be used for good or bad, so it’s an oversimplification to label shari’a as simply in opposition to human rights. Debates among Muslims about the meaning of shari’a are much more complicated, because some activists also use shari’a to justify women’s rights. This research will fill his next book, which he has begun as a visiting fellow at Princeton University in 2015–16.

Returning to California

While Massoud studied religious law in Sudan and Somalia, the word “shari’a” started appearing in the newspapers and television reports in the United States. The specter of radical fundamentalists cast a frightening shadow for many Americans whose primary exposure to Muslims and Islam was through the lens of the war on terror. “Since 9/11, things have changed,” Massoud said. “Some people fear Islam or Muslims.”

Even as he gathered data in Somalia, Massoud said he realized he knew little about the role shari’a plays in the lives of American Muslims. In a secular legal system, he wondered: “How are Muslims interpreting shari’a? How do people engage with practices of Islamic law and human rights? These are questions that not only Muslims in Somalia are asking themselves. Muslims in California are asking and answering these questions, too.”

With a project dubbed “Shari’a Revoiced,” Massoud partnered with Kathleen Moore, chair of the Department of Religious Studies at UC Santa Barbara, who studies Islamic law. They secured long-term funding to set up an interdisciplinary studio that brought together scholars, journalists, filmmakers, and visual artists to talk about Islamic law. The goal of the collaboration was to bring the discussion about the Muslim experience in America to a wider public audience than most political or religious scholarly work usually garners. It’s a facet of the project, Massoud and Moore noted, that is critical in an era of Islamophobia.

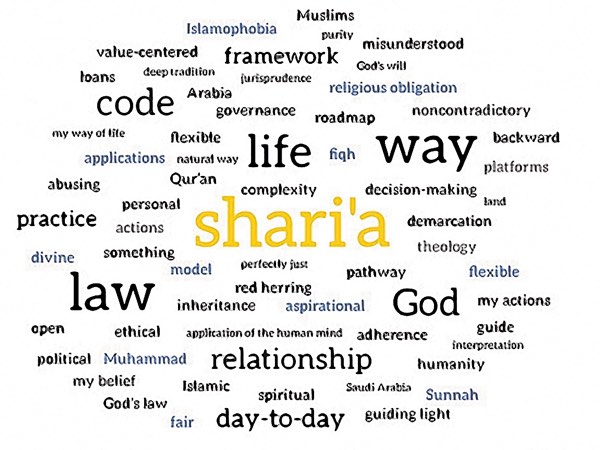

The two led a team that invited input from Muslim community leaders in California on the interview protocol they developed. After more than 100 interviews with Muslims in California, they distilled key words such as “pathway,” “Sunnah” (sayings and teachings of the prophet Muhammad), and “divine,” much the way Massoud extracted themes from his interviews in Sudan. This word list reflected ideas, such as “religious obligation,” “jurisprudence,” and “Islamophobia” that interviewees associated with shari’a.

One surprising result, said Moore, was how much people within a single household can differ in how they interpret shari’a. Those differences demonstrate how flexible the interpretation of shari’a can be, despite the common perception among non-Muslims of shari’a as a rigid set of laws.

“For instance, a husband might rely on the written law, created by judges living in the thirteenth century. He might think that has a lot of authority,” said Moore. “Whereas the wife might say, ‘all of that stuff is history and it’s not relevant to me living in America. God granted me intellect so that I could reason about these things and I can know what pleases God.’”

Despite the groundbreaking nature of Massoud’s work and the international acclaim he’s received, Massoud doesn’t see its role as prescriptive. He’s been asked what should be done in Sudan, but said a clear answer cannot come without an appreciation of legal history. Before we can know how to use the law in a place like Sudan or Somalia, Massoud argued, we must understand how it’s already been used.

“It’s only when we realize how law has been used—as a force for bad or a force for good—that we can understand our own goals and hopes for the law in the future,” said Massoud.