Cloudy with a chance of life

Astrophysicists probe distant planets

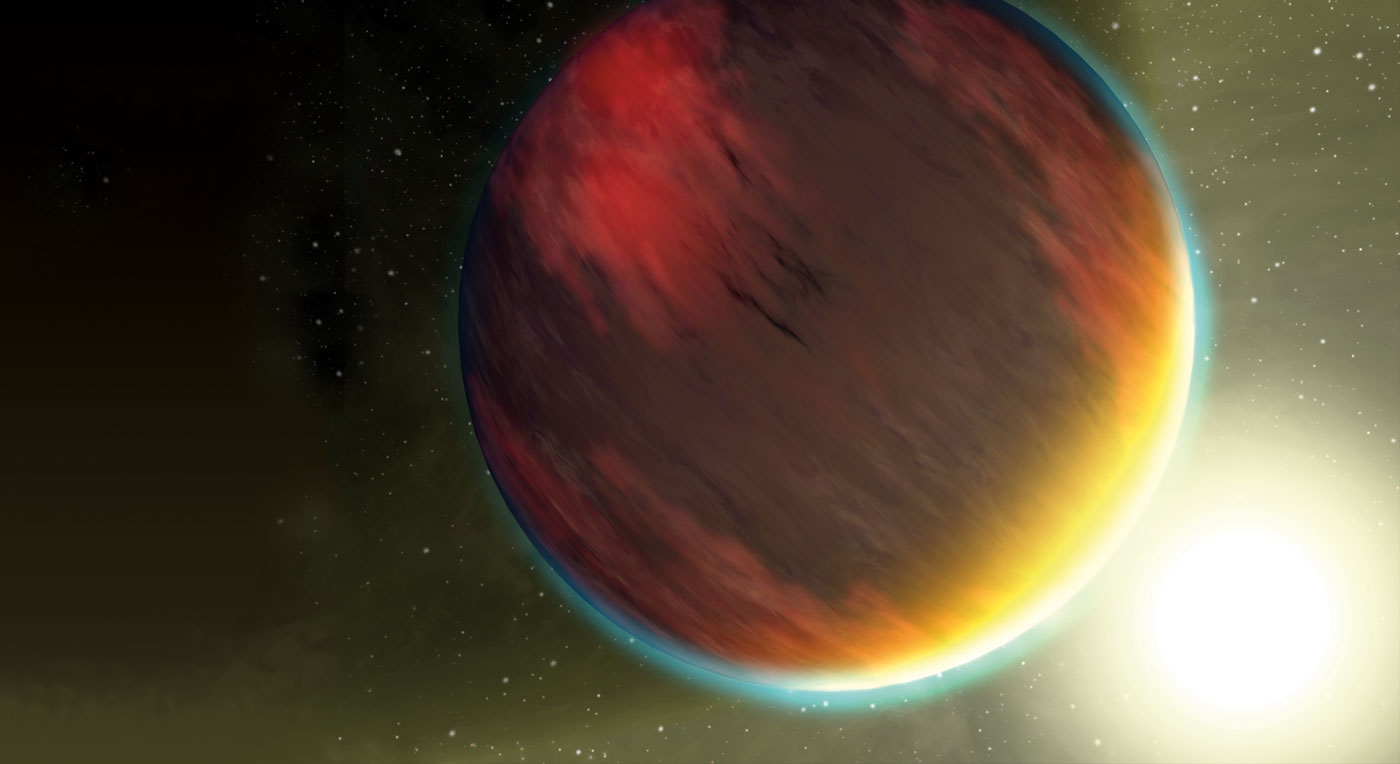

HD 209485b would make a lousy place to live. Anything that could call this exoplanet “home” would have to withstand air temperatures hotter than the inside of a volcano and storm winds gusting faster than the speed of sound. Clouds of vaporized rock would make for sunsets of brilliant green—if only they weren’t so deadly.

More astounding, perhaps, than the bizarre environment of HD 209485b, is the fact that we know anything about it at all. The gas giant orbits a star 150 light-years away; a distance so vast that even our most powerful telescopes can’t yet glimpse the planet.

These vast distances are a daily commute for Jonathan Fortney, an astrophysicist at UC Santa Cruz and director of the university’s nascent Other Worlds Laboratory. He’s helped detect water, salt clouds, and vaporized metals in the atmospheres of planets even farther away than HD 209485b. And most appear to be similarly hellish. “There’s a crazy range of inhospitable and more inhospitable atmospheres,” he said. “Planets have a tremendous amount of character.”

While Fortney investigates the atmospheres of distant planets, his colleague Pascale Garaud, professor of applied mathematics, studies the motions of fluids in their interiors to better understand convection and its role in heat transfer. Together, Fortney and Garaud are refining not only the models governing planet formation and evolution, but also some of the basic principles of astrophysics.

Stars aligned

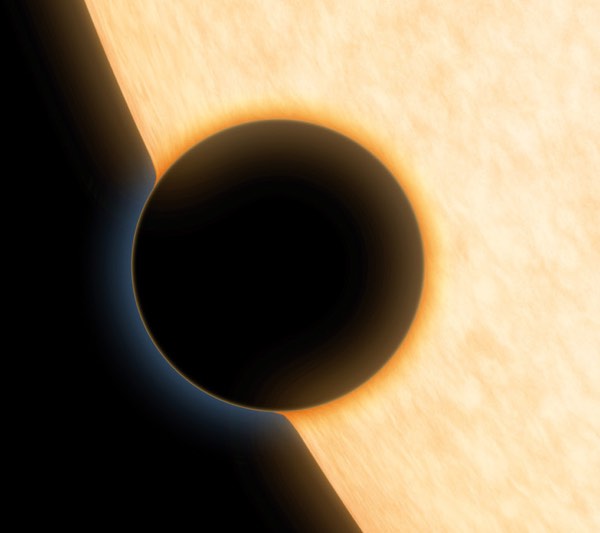

When researchers first detected an extrasolar transit —a planet outside our solar system passing in front of its star—Fortney was studying planetary interiors and atmospheres as a doctoral student at the University of Arizona. Soon after that observation, Fortney and his adviser, William Hubbard, penned one of three landmark papers that demonstrated atmospheric information could be derived from the starlight transmitted during transits.

“That was a big deal at the time when the first transits were being observed,” said Hubbard. “There was a lot of skepticism about whether or not you could really do this.”

Later, Fortney collaborated with the Kepler Mission, a NASA space telescope designed to find Earth-like planets elsewhere in the Milky Way. In 2011, Fortney and the Kepler team gained considerable media attention for their research on Kepler-11, a planetary system that contains at least six planets tightly packed around their star. Fortney and his students showed how Kepler-11’s “super Earths”—planets intermediate in size between Earth and Neptune—are gradually losing their atmospheres due to intense heating from their parent star.

Enigmatic exoplanets

At its most basic level, a transiting planet is a black dot, blocking light as it passes directly between its star and the Earth. But at a higher resolution, even the thinnest veneer of atmosphere will absorb or scatter a small amount of light instead of blocking it. And every element, molecule, cloud, and speck of dust in that atmosphere will influence light differently. So, if the Hubble or the Spitzer space telescopes record a dip in starlight during a transit, they also record any signature left behind by a planet’s atmosphere.

From a transit, researchers isolate the light that penetrates the atmosphere and produce a transmission spectrum—a graph of the light’s intensity across a range of wavelengths. The challenge, then, is decoding the spectrum. And that’s where Fortney comes in. By combining that data with information about the planet’s orbit, size, and temperature, Fortney’s research group creates thousands of atmospheric simulations and searches for the best fit. They determine the chemical makeup of the atmosphere and infer which materials are in the spectrum.

Some of those inferences are remarkably detailed. “If you have a really hot planet in a one-day orbit, you can actually have your day side be hot enough that you have vaporized rock,” Fortney said—similar to HD 209485b, which orbits its star in three-and-a-half days. “Then it flows onto the night side where it’s cold; it just collapses and freezes onto the surface.”

The easiest atmospheres to study, Fortney said, are the thick ones around huge planets in tight orbits around their star—like the hydrogen- and helium-rich “hot Jupiters” similar to the gas giant in our own solar system, except they’re blisteringly hot. While hot Jupiters make up the majority of the 60 or so exoplanets whose atmospheres have been described in any detail, recent discoveries of “super-Earths” have pushed this exo-atmospheric science to smaller planets.

Sometimes, Fortney solves planetary mysteries— such as the case of the missing water. For nearly eight years, atmospheric observations of many hot Jupiters detected far less water than planetary models predicted. Astrophysicists wondered if their models could be wrong. “It would be surprising to find a giant planet that did not have water,” Fortney said. “So the question is, where do you hide all that water?”

But it turned out water wasn’t the only thing missing; other chemical signatures appeared muted, too. So what could dampen multiple sections of the transmission spectrum? This past December, Fortney coauthored a paper that put forth an answer: clouds. Masses of dust and vaporized metals obscure transmitted light—just as water clouds do at home. “Earth’s clouds are white, and what white means is that they don’t really have any absorption features,” he said. “They’re just scattering all wavelengths of light the same amount.”

Finding the missing water wasn’t just a chance to confirm planetary models or even to find signs of life. The exploration itself is important, said Fortney. He wants to know how planets can vary so much—from salt clouds on some, metallic atmospheres on others, to something completely different on Earth.

Reducing error bars

Fortney will discuss these questions when dozens of like-minded explorers visit UC Santa Cruz for the Kavli Summer Program in Astrophysics. Focused this year on exoplanet atmospheres, with Fortney as science director, it’s the fourth in a series of summer research institutes founded by Pascale Garaud.

Like Fortney, Garaud is something of a consultant, lending her skills as a theorist to teams of observers working in natural systems. Currently funded by four National Science Foundation grants, and one from NASA, her fluid dynamics research ranges from convection in the tropical ocean to the interiors of stars. “That’s the beauty of fluid dynamics,” she said. “The same equations describe all sorts of different fluids.”

But Garaud’s passion, and Ph.D., is in astrophysics—particularly in refining models that don’t seem to jive with observations. For instance, calculations of Saturn’s age based on its observed temperature and models of thermal convection miss the mark by billions of years—which either means the planet formed much later than the rest of the solar system or planetary thermal models are missing some important variables. She’s trying to figure out if the combined weight of all the droplets in Saturn’s helium rain could play a significant role in slowing down the planet’s thermal evolution.

“The models that are being used to study heat transfer are ancient, and they’re very, very basic,” she said. “The better we refine the stellar and planetary models, the better we’ll refine everything that we know about astrophysics.”

To make the field more robust, Garaud founded a six-week summer astrophysics program. It teams 15 graduate students with faculty members and postdoctoral students to pursue hyper-focused research projects. She modeled it after the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Program at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in southeastern Massachusetts, of which she is a permanent faculty member.

“Nobody really believes it’s possible to do decent research in such a short of amount of time,” Garaud said. But, in just three summers, program participants have published more than 30 papers on topics ranging from gravitational dynamics and magnetism to star and planet formation.

“This idea that you’ve got six weeks of relative isolation locked up with other people who are equally excited about science is really a privilege and a luxury in the academic year,” said Subhanjoy Mohanty, an astrophysicist at Imperial College London who joins the program’s faculty every year. In his fourth paper resulting from Garaud’s program, Mohanty recently published a study on the habitability of planets around a class of relatively small and cool stars known as red dwarfs.

A new era

Two decades ago, the only observable planets beyond Earth were the others in our own solar system. Today, researchers have confirmed close to 2,000 new planets and another 4,600 likely candidates—not to mention the possibility of a mysterious “Planet X” beyond Pluto. At the inaugural all-exoplanet conference in 2002, Fortney recalled about 100 attendees. Now, that number of researchers focus on atmospheres alone.

In the next 10 years, he said, two soon-to-be-launched instruments could jump-start the field all over again: the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, designed to find transiting planets around stars relatively close to our solar system, and the James Webb Space Telescope, which will collect more precise transmission spectra in a broader range of wavelengths. Together, these instruments will gather more information about planets that are smaller and more difficult to detect than hot Jupiters, including planets as small as Earth.

“Things that we’re getting hints of today will become real ironclad discoveries,” Fortney said. “We’ll find planets like Dune [Frank Herbert’s science-fictional planet] that are probably mostly dry, and we’ll find icy planets. All those things exist.”

And if there’s life out there, they may well find that, too.