Brief inquiries

Computer Science

Open source resource

After UC Santa Cruz alum Sage Weil earned his doctoral degree in computer science he didn’t let his thesis work languish. Instead, he spent seven years refining the open source storage solution, Ceph, and then created a startup for the platform, which sold to Red Hat last year. Now, with major gifts that total $3 million for research in open source software, Weil is creating similar opportunities for other UC Santa Cruz students.

“Sage was a brilliant student and deeply committed to open source software as a model for how to move computer science forward,” said Scott Brandt, vice chancellor for research and computer science professor. “His success was quite extraordinary, and he wanted to give back to the university.”

With matching funds from the UC Presidential Match for Endowed Chairs, Weil’s gift of $500,000 established a $1 million endowment for the Sage Weil Presidential Chair for Open Source Software. An additional $2 million supports the Center for Research in Open Source Software (CROSS), directed by computer science professor Carlos Maltzahn.

“CROSS will bridge the gap between student research prototypes and successful open source software products,” said Maltzahn. “We’re the first graduate-level program that offers this completely new way for students to get involved in a very sophisticated professional community,” he added.

The newly minted CROSS has already attracted three founding member companies: Toshiba, SK Hynix Memory Solutions, and Micron.

Environmental Toxicology

Heavy metals

Last year, the California ban on lead-based ammunition drew on scientific evidence developed by UC Santa Cruz toxicologists Donald Smith and Myra Finkelstein. With a unique “fingerprinting” technique, they directly linked the ammunition to deadly levels of lead poisoning in California condors.

Although lead gets lots of attention, it isn’t the only metal that Smith worries about. In people, manganese toxicity from contaminated water, soil, or dust is an emerging problem in many countries—including our own.

Essential for our bodies at low levels, excessive amounts of manganese can impair cognitive function and cause conditions similar to Parkinson’s disease.

In two separate NIH-funded studies, Smith documented manganese levels in the body and corresponding changes in neurological behavior: one in children with high environmental exposure; another in experimental animal models exposed to manganese as neonates.

The results of the animal study, described in Environmental Health Perspectives, showed that developmental exposure to manganese causes lasting attention and fine-motor deficits. The deficits in the animals parallel those observed in the study on children.

Smith is now exploring the underlying mechanisms of manganese toxicity in the brain and how medications, such as Ritalin, might mitigate those impacts.

UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves

Green gifts

Outside the classroom doors, UC Santa Cruz provides stewardship for five natural laboratories located along the Central California coast. These protected ecosystems belong to a network of undisturbed sites that are set aside for research in the UC Natural Reserve System.

Each of these pristine places will benefit from a $500,000 gift from the Helen and Will Webster Foundation, which, with matching funds from the UC Regents, will establish a $1 million endowment for the Wilton W. Webster Jr. Presidential Chair for the UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves.

Four of the UC Santa Cruz reserves are part of 39 areas managed by the University of California, encompassing over 750,000 acres across California. These UC Santa Cruz reserves include Año Nuevo Island Reserve, Fort Ord Natural Reserve, Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve, and Younger Lagoon Reserve. A fifth, the Campus Natural Reserve, is also managed by UC Santa Cruz.

The reserves offer research opportunities for students of all ages, ranging from K–12 programs at Fort Ord, overseen by Gage Dayton, the administrative director of the UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves, to the multi-reserve project led by UC Santa Cruz biologist Barry Sinervo for the Institute for the Study of Ecological and Evolutionary Climate Impacts.

“Getting students out in the field is transformative,” said Donald Croll, the faculty director of the UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “This gift will help us inspire the next generation of conservationists.”

Film & Digital Media

Oscar nominee

A first-ever film effort by Dee Hibbert-Jones, UC Santa Cruz associate professor of art and digital art and new media, earned an Academy Award nomination for_ Last Day of Freedom_, a short-subject documentary. Her work also garnered a 2016 John Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship for film and video.

Six years in the making, in collaboration with San Francisco artist Nomi Talisman, the film tells the story of a man who turned in his war-haunted brother for committing murder.

“We wanted to reach behind the headline news and look at the effect of the death penalty on the families and communities left behind,” said Hibbert-Jones, a fine artist by training. They used animation to put psychological distance between the viewer and the powerful story, she explained. “My arts research has always crossed genres and borders. When I teach public art I explore the politics of public space, and I’m interested in the ways public and private lives impact and intersect,” she said.

Last Day of Freedom is the first in a trilogy of films planned about the criminal justice system. The documentary qualified for the nomination after winning the 18th annual Full Frame Documentary Film Festival jury award for Best Short film.

Ecology & Evolutionary Biology

Bat plan

Four new grants, totaling almost $300,000, are helping UC Santa Cruz biologists Marm Kilpatrick and Winifred Frick advance research on white-nose syndrome, a malady that has killed more than 6 million bats since 2006.

The pathogenic fungus makes the bats wake from hibernation too frequently. They exhaust their stores of fat and starve to death, explained Kilpatrick, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

Last November, with grants from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bat Conservation International, and the Nature Conservancy, Kilpatrick and Frick started field trials with potential treatments.

Earlier work by UC Santa Cruz graduate student Joseph Hoyt showed that some bats have skin bacteria that inhibit the fungus.

In the trials, groups of bats roosting in a mine got their skin sprayed with one of three things: Hoyt’s fungus-killing bacteria, an anti-fungal extract made from chitosan (a protein in the outer skeleton of insects), or a treatment-free control.

The bats were tagged with a device to record when each animal left the mine. If the treatments work, the bats will survive until spring when flying insects return.

“If this works,” said Kilpatrick, “we could help species heavily impacted by disease.”

Molecular, Cell, & Developmental Biology

Why Wolbachia?

Cell biology studies could offer high-impact solutions for neglected tropical diseases that afflict the “bottom billion,” the poorest people in the poorest countries, wrote UC Santa Cruz biologist William Sullivan in an essay published in Molecular Biology of the Cell.

For example, when researchers discovered that a bacterial parasite of worms caused the debilitating inflammatory reactions of African River Blindness—not the roundworms that migrated into human tissue—the door opened for treatment with common antibiotics.

Sullivan’s team developed the high-throughput screening method to hunt for drugs that might kill this sneaky bacteria, called Wolbachia. In collaboration with the UC Santa Cruz chemical screening center, they found an FDA-approved drug that killed Wolbachia. The same drug also kills the long-lived worms because they need the bacteria to survive.

Now Sullivan’s team, in collaboration with the California Institute for Biomedical Research, is screening more than 170,000 compounds for even more potent anti-Wolbachia treatments. With further study, Sullivan hopes to better understand how the parasitic bacteria manipulates its host worm, and find drugs to disrupt those interactions.

“The goal is to find a drug that could be used once, or yearly; something suitable for a mass drug administration campaign,” said Sullivan.

Agroecology

Insect diversity

From coffee plantations to urban gardens, UC Santa Cruz environmental studies professor Stacy Philpott has been digging around dirt for decades.

“I look at ways to create win-win situations that protect insect biodiversity and help agriculture thrive,” said Philpott, who holds the Ruth and Alfred Heller Chair in Agroecology and directs the UC Santa Cruz Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems.

On coffee plantations, her studies have shown that clearing too many trees makes ant diversity decline. Without that biodiversity, plantations lose valuable resources, such as pest control.

Closer to home, Philpott and her students spent three summers studying 19 different Central Coast gardens to learn which factors enhanced insect biodiversity. As urbanization increases, these small green spaces can provide important insect habitats.

Not surprisingly, growing a wider variety of garden plants supported a greater range of insect species. But they also found the surrounding landscape—trees, grasslands, cement, or ground cover—affected biodiversity. For example, in research published in Environmental Entomology, UC Santa Cruz alum Michelle Otoshi showed that spiders were more abundant with garden mulch.

In the future, Philpott will return to coffee plantations to study how changes in bee and ant diversity affect the microbiome of coffee flowers.

Sociology

Citizen gain

The term “denizen” is used to describe an inhabitant who is not a formal citizen, but not necessarily an undocumented immigrant either. It’s a word that fits more than 60 million refugees who have fled their homelands, according to UN Refugee Agency data.

“What does it mean to be a denizen in a world that is organized around, and by, nation-states?” asked Catherine Ramírez, associate professor of Latin American and Latino studies and director of the Chicano/ Latino Research Center at UC Santa Cruz.

Such questions will be explored during a year-long “Non-citizenship” seminar, planned by Ramírez and four other UC Santa Cruz professors: Juan Poblete, literature; Felicity Amaya Schaeffer, feminist studies; Sylvanna Falcón, Latin American and Latino studies; and Steven McKay, sociology. The seminar is funded by a $175,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation John E. Sawyer Seminar on the Comparative Study of Cultures.

Ramírez hopes to foster conversations across the borders of academic disciplines, geographical regions, and even time periods—by including historical perspectives as well as current events.

Education

Personal ed

Big data could help close achievement gaps between underserved students and their peers in the Silicon Valley region.

Educational intervention often takes a blanket approach, noted Rodney Ogawa, UC Santa Cruz professor emeritus of education. But a regional database that draws information from public schools, online educational program providers, and health and human service agencies could enable detailed analyses that lead to personalized education plans.

With a $356,542 National Science Foundation grant, Ogawa and his colleagues built partnerships for the Silicon Valley Regional Data Trust, a database for San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties.

One impetus for this project was a study, published in the American Journal of Education by Ogawa, Betty Achinstein, and Marnie Curry, of three predominantly Latino high schools with high rates of college-bound students. Despite intensive efforts, those at-risk students often weren’t prepared to academically thrive in college.

There were organizational barriers to students’ success, said Ogawa. He thought: Why not use data the way they do in medicine or astronomy to breakdown boundaries and answer intractable questions?

“The goal is to begin personalizing educational services so that the kids and families most at risk for poor outcomes in schools and elsewhere can be able to begin to turn the corner,” said Ogawa.

Astrophysics

Mistaken idenity

Dark matter comprises more than 85 percent of matter in the universe. Still, no direct hints about its particle nature have been conclusively detected.

Recent attempts to confirm a dark matter decay signal from the dwarf galaxy Draco came up empty handed, reported UC Santa Cruz physicists, Stefano Profumo and Tesla Jeltema.

The signal claims, by two separate research groups, were based on observations of an anomalous bright line among X-ray spectra emitted from clusters of galaxies considered to be the largest dark matter–dominated systems in the universe.

A bright line was found at 3.5 keV, a result predicted by one model in which a sterile neutrino would decay into a 3.5 keV photon and an ordinary neutrino. However, ordinary potassium ions can create similar spectral lines. A follow-up study, in an area without potassium, detected no bright line. This ruled out the sterile neutrino dark matter hypothesis at a 99 percent confidence level, explained Profumo.

“We’re back to the drawing board, but there’s no shortage of dark matter candidates,” he added.

“If a signal is found, and confirmed, then we’ll learn something fundamental about particle physics theory, which doesn’t include dark matter right now,” said Jeltema.

Computer Engineering

Hybrid vigor

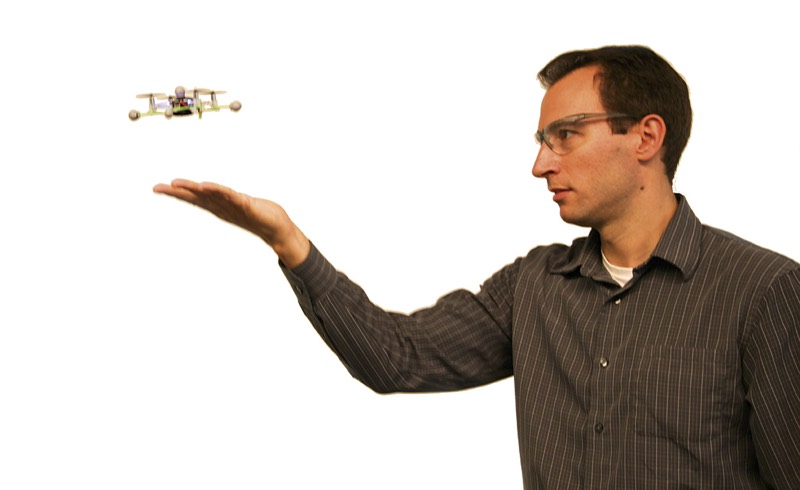

Flying robots might not appear to have much in common with energy grids. To function smoothly, however, both use hybrid systems that combine stop-start action with continuous movement. Developing algorithms for these systems is a specialty of Ricardo Sanfelice, associate professor of computer engineering.

“I enjoy solving applications that combine physics and computational components,” said Sanfelice.

One of those applications enables “smart grids” to link off-and-on sources of renewable energy, such as solar power, with the continuous electric currents of standard electricity. A patent is pending for that hybrid control algorithm.

With a $432,000 National Science Foundation grant, Sanfelice and a colleague from the University of Arizona are now developing a system to enable groups of unmanned vehicles to work together under uncertain conditions.

A key problem is that computer calculations could take longer to make than actual movements—potentially putting vehicles and people at risk. Introducing a metric, called uncontrollable divergence, allows the computer to calculate tradeoffs between accuracy and speed to determine its best trajectory. Sanfelice’s team described this “computationally aware cyber-physical system” in the journal _Autonomous Robots. _

Sanfelice hopes to gather an interdisciplinary group of his campus colleagues to advance the development of these complex cyber-physical systems.

Planetary Science

Moonmaker

The rotational forces on spinning heavenly spheres creates bulges at their equators. A faster spin exerts a stronger force and bigger bulges. However, the Earth’s moon only rotates about once a month. So, for centuries, astronomers wondered: With so little spin, why the lemon shape?

Billions of years ago, the Moon was made of rock sheets floating on a sea of magma, said Ian Garrick-Bethell, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz. The Moon’s distorted shape resulted from the combined effects of early tidal forces on a hot Moon, plus rotational forces as the surface later cooled unevenly, according to his paper published in Nature.

Garrick-Bethell drew insight from similar ideas about the shape of Europa, the cool and watery moon of Jupiter. A detailed topographical analysis of the Earth’s moon, based on data from laser altimeters and studies of gravity-field perturbations, supported these conclusions. Also involved in the study was UC Santa Cruz professor of Earth and planetary sciences Francis Nimmo.

This work expanded on earlier studies, published in Science, which used tidal forces to explain unusual features on an area of the Moon called the farside highlands.

Ocean Sciences

Seal-ective hearing

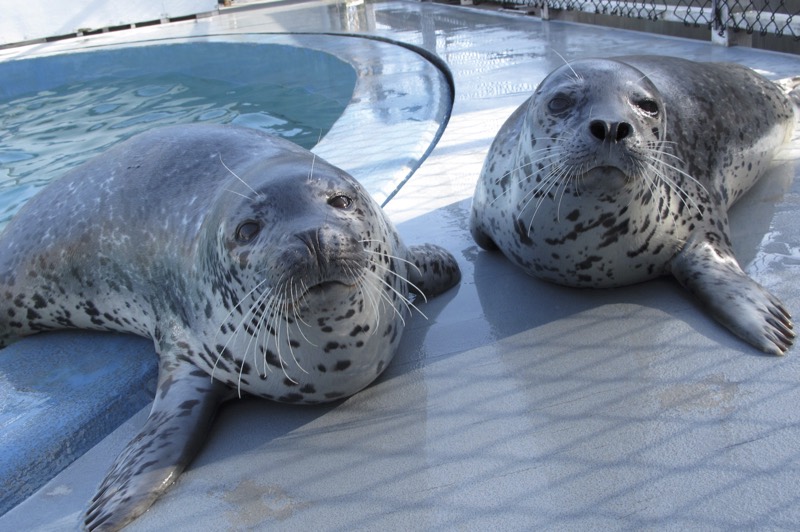

Rising levels of man-made noise in the Arctic are degrading the acoustic habitat of ice-living seals.

To learn more about how noise pollution affects these animals, researchers at UC Santa Cruz’s Long Marine Laboratory partnered with two pairs of rarely studied Arctic species—spotted seals and ringed seals—to test their hearing.

The results of those studies, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, showed that both species are highly sensitive to sounds both above and below the water’s surface, said Jillian Sills, lead author and a doctoral degree candidate in the Department of Ocean Sciences.

Moreover, the amphibious animals didn’t lose land-based hearing in favor of underwater sound, noted lab director Colleen Reichmuth, a coauthor on the papers.

The research team tested the seals’ hearing under quiet conditions and against background noise, from frequencies as low as 100 Hz to ultrasonic frequencies higher than 70 kHz. Interestingly, the seals showed a wider hearing range under water compared to on land, suggesting that the hearing mechanisms differed in each environment.

Next, the investigators will create auditory profiles for the rarely studied bearded seal. All the data will help establish regulatory criteria for noise exposures to protect free-ranging marine mammals.

Coastal Sustainability

Sea Change

The kelp forests along the Pacific coastline provide a rich habitat for marine species, ranging from microscopic algae to marine mammals. They also offer a dynamic place to study environmental change for Kristy Kroeker, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz, who received a five-year, $875,000 Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering.

In previous research Kroeker found that increasing acidification and temperature altered algae populations. In turn, these changes affected the animals that live and feed on the algae and, ultimately, the resilience of rocky reef ecosystems.

Now, she’ll place ocean sensors from Baja California to Alaska to track changing carbonate chemistry, oxygen, and temperature levels. She’ll follow the corresponding changes in the algae and marine herbivores.

In addition, Kroeker is experimenting with small granite tiles that provide blank slates for algae, coralline algae, and small grazers to establish themselves. Watching these communities build themselves will improve understanding about how kelp beds come back after big storms, and the ways environmental changes might affect these dynamics.

“These are simple ecological experiments in succession and species interactions—except that we’re doing them across thousands of kilometers,” said Kroeker.

Sociology / Environmental Studies

Tapped out

Water can be the currency that builds wealth or reduces poverty. However, access to water doesn’t always command the same attention—or intervention—as the money gap between rich and poor.

Such inequities led UC Santa Cruz sociology professor Ben Crow and his collaborators to draft “The Santa Cruz Declaration on the Global Water Crisis.” The document built upon the 2013 Equitable Water Governance workshop, led by Crow and Colleges Nine and Ten provost Flora Lu.

“Although limited water supply and inadequate institutions are indeed part of the problem, we assert that the global water crisis is fundamentally one of injustice and inequality,” noted the declaration.

Studies by Crow and Lu have shown these disparities are everywhere: in Global South populations excluded from water sources; in northeastern Ecuador where indigenous Amazonians struggle daily to find clean water in oil-contaminated communities; and in Central California where farmworkers compete with crops for uncontaminated water.

Safe drinking water isn’t enough to eliminate disparities, argued Crow, in a paper coauthored with UC Santa Cruz alum Matt Goff and published in Water International__. Crow’s two-year Kenya study, which included putting GPS devices on “jerry cans” to track the work of collecting water from vendors’ taps, showed that time spent getting water—mostly by women—detracts from child care, small enterprise, and freedom for community involvement.

Instead, providing “liberatory capabilities,” such as water taps inside households, could be more effective to reduce poverty.