A Cold Trail

Researchers drill into Antarctic ice to understand the effects of climate change

Slawek Tulaczyk keeps a shotgun case in his office. It’s an odd piece of equipment for a glaciologist. More appropriate are the ice axe, crampons and helmets lying around in his room. But the case came in handy for hauling a gun to Alaska, where he was “harassed by a really weird bear.” Does he take the gun to Antarctica? “No,” he said. “That’s the nice thing about working in Antarctica. It’s a pretty safe place.”

Only someone who has been to Antarctica eleven times would call the continent safe. Sure, there are no bears to scare off, but dangers lurk everywhere, especially in the remote terrain where Tulaczyk works. For almost a decade now, his team has been studying the Whillans ice stream in West Antarctica–a river of ice hundreds of kilometers long that is, oddly enough, slowing down, even as climate change is causing glaciers and ice streams elsewhere to speed up.

These ice streams feed into the ocean, and the pace at which they flow directly affects global sea levels. So, if Tulaczyk and his colleagues can understand the unusual behavior of the Whillans ice stream, their work will help climate scientists fine tune their models and better predict the relentless rise of sea level due to global warming. To decipher the dynamics of the Whillans ice stream, the team is looking at two main features: one is the subglacial Lake Whillans that lies nearly three-quarters of a kilometer beneath the ice stream; the other is its “grounding zone,” where the ice lifts off from land and begins floating on water.

A quirk of geography first focused attention on the Whillans ice stream, one of a handful of massive ice streams that carry ice from the West Antarctic ice sheet down to the Ross Ice Shelf. For scientists studying these ice streams in the 1960s and 1970s, before there was GPS, Whillans was the first ice stream they encountered that was close to the Transantarctic Mountains. In the otherwise featureless terrain of snow and ice, the mountains were an invaluable aid for navigation. You couldn’t get lost studying Whillans, so it became the hub of scientific activity.

During the early 1960s, the Whillans ice stream was moving at about 600 meters per year–which might not seem like much, but for a river of ice about 800 meters thick and about 100 kilometers wide, that’s a lot of ice entering the ocean. “It discharges as much water as the Missouri River,” said Tulaczyk, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz, and one of the three principal investigators on the Whillans Ice Stream Subglacial Access Research Drilling (WISSARD) project.

But Whillans is slowing down. Modern measurements using GPS show that its speed is now below 400 meters per year. This is at odds with what’s happening in other parts of West Antarctica.

For instance, farther along the coastline, the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers are both speeding up. These two glaciers together drain about five percent of the West Antarctic ice sheet into the Amundsen Sea. When the ice from a glacier enters the sea, it doesn’t melt right way. Rather, it forms a floating platform–called an ice shelf–which acts as a buttress, preventing the glacier from sliding faster and faster into the ocean. But climate change is thinning such ice shelves, causing the glaciers behind to speed up, leading to what glaciologists call a negative mass balance. The water that would otherwise remain frozen on Antarctica is now ending up in the ocean faster than in the decades past, slowly raising sea level worldwide.

For now, this is not the fate of Whillans or some of the other ice streams that empty their ice into the Ross Sea, forming the Ross Ice Shelf–the biggest mass of floating ice on the planet, with a surface area the size of Texas. Whillans is decelerating dramatically. “Within decades, if I live long enough, I might see this ice stream completely shut down,” said Tulaczyk.

Does that mean climate change is having no effect on the Whillans ice stream? Tulaczyk’s answer is an emphatic “no.” Rather, Whillans’ behavior tells us that the Antarctic ice sheet is so big that it has its own internal dynamics. Even without any climate change, these ice streams would be slowing down and speeding up. “Why do these changes take place at the rates that they do? That’s the key thing we need to understand–if you ever want to build reliable models of predictions of what’s going to happen to an ice sheet 100 years from now,” said Tulaczyk.

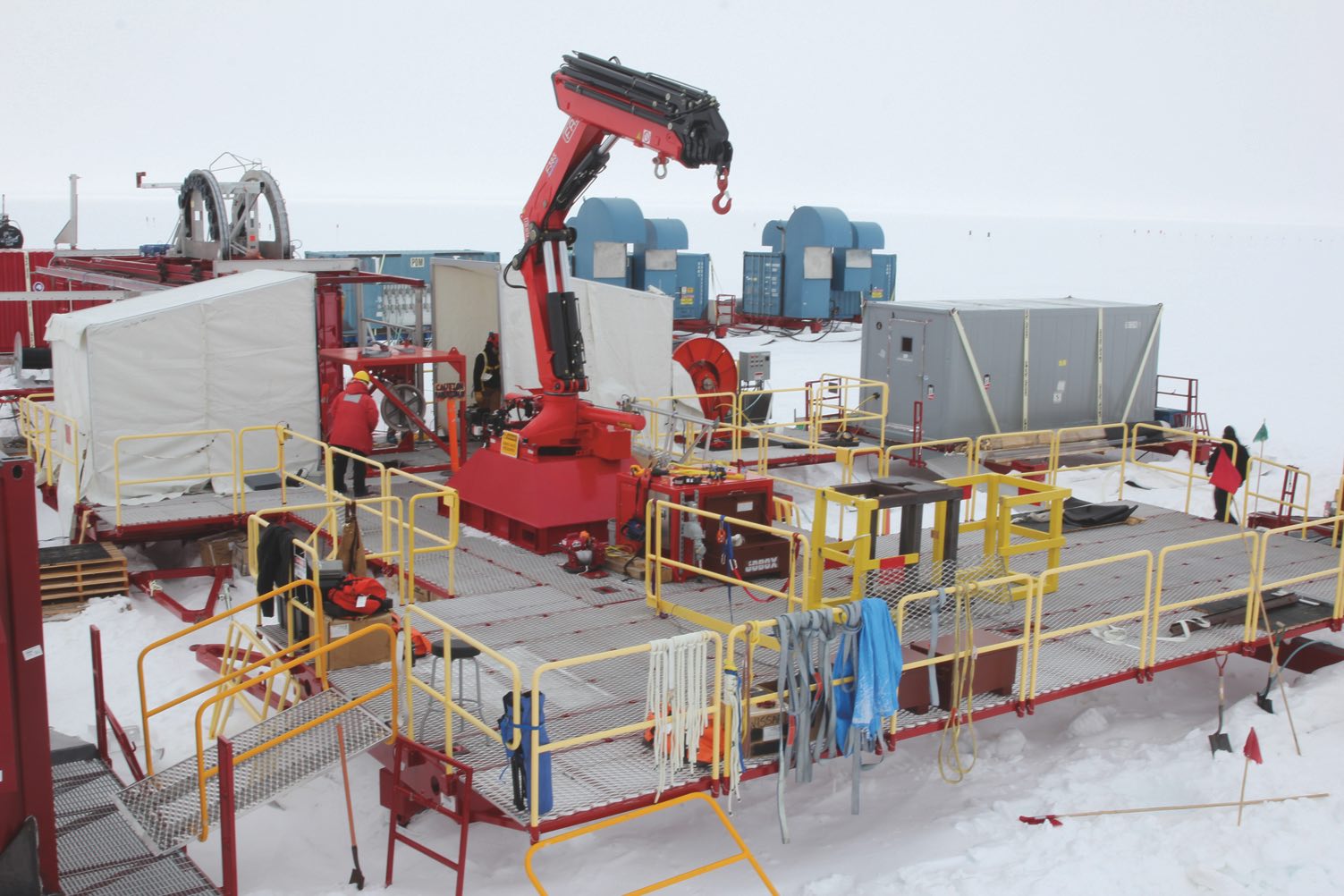

In January 2013, the team became the first to drill “cleanly” into a subglacial Antarctic lake. With a sterilized nozzle spewing out near boiling water at high pressure (the water was also filtered and irradiated with UV light to prevent contaminating the pristine environment), they melted a hole through nearly 800 meters of ice to reach Lake Whillans. One perplexing piece of the Whillans puzzle is that the lake isn’t always there. Periodically, the water appears and disappears–as do many other subglacial lakes. The process begins when meltwater from the base of the Antarctic ice sheet ponds up because something in the bedrock beneath the ice dams the water. The lake, as it forms, begins pushing up the ice–these changes in ice elevation led to the lake’s discovery in the first place. At some point, the water pressure becomes too much; the dam breaks and the lake empties. In the case of Lake Whillans, this process has happened three times since it was discovered in 2007. Tulaczyk wondered: Does the periodic release of water have any effect on the movement of the ice stream?

To answer that question, Tulaczyk needed to under-stand the movements of the Whillans ice stream and its relation to the lake beneath. He’d have to embed instruments in the ice and deploy them on the surface. For help, Tulaczyk turned to UCSC colleagues, seismologist Susan Schwartz and engineer Daniel Sampson. Along with veteran driller Dennis Duling, of the U.S. Antarctic Program, the team spent two backbreaking summers drilling six boreholes into the Whillans ice stream.

“You are either driving a snow machine for hours on end, or packing up sleds to trail along behind you, and then having to set up camp and fall asleep. It was that kind of work,” said Sampson.

And there are dangers too. One day, Sampson slipped and a fully loaded sled, weighing nearly half a ton, ran over his legs. “I screamed thinking I was done for,” he said. “Fortunately, the snow was soft enough that my legs went into the snow.” He was fine.

But all such work is helping make sense of the way the Whillans ice stream moves.

The instruments have already revealed two things. One is that the relatively small discharge of water from Lake Whillans (about 0.1 cubic kilometers) is not having much of an effect on the movement of the ice stream. The second insight has to do with why the ice stream is slowing down. “This particular ice stream locks up, doesn’t move, and then twice a day, it kind of leaps forward about half a meter,” said Schwartz. The twice-a-day movements are related to tides. But the researchers also see that the ice stream occasionally skips a beat, leading to its overall deceleration.

Over the next few years, the team wants to understand why the ice stream gets stuck in the first place, and what causes it to break free, a dynamic that Schwartz calls “stick-slip motion.” Climate models have to account for all the ways in which ice streams and glaciers can end up in the ocean. “People have not considered this kind of frictional stick-slip motion in models, and that could have a very large effect on rates,” said Schwartz.

Even without such detailed knowledge, the effect of climate change on Whillans is clear. In January 2015, when the drillers became the first to ever penetrate an ice stream near its grounding zone, their instruments and cameras found signs of fresh sedimentation. Rocks, once embedded in the ice, have been raining down on the sea floor. A preliminary analysis showed this top layer of sea-floor sediment formed during the past few decades. This means the ice is melting, dropping rocks, and then retreating.

“Climate change is potentially pushing the ice sheet back, shrinking it,” said Tulaczyk. So, while Whillans may be slowing down, the warming sea surrounding Antarctica is nonetheless eating away the ice at its margins.

“This is the frontline of climate change in Antarctica, the fight between the relatively warm sea water and the ice itself,” said Tulaczyk. It’s clear the ice is losing, but just how much of a fight is it putting up? Knowing that will help us better predict future sea- level rise. “We want to go back,” he said. But even as he prepares his next project proposal, Tulaczyk is aware that climate change isn’t waiting.