Brief inquiries

Astrophysics

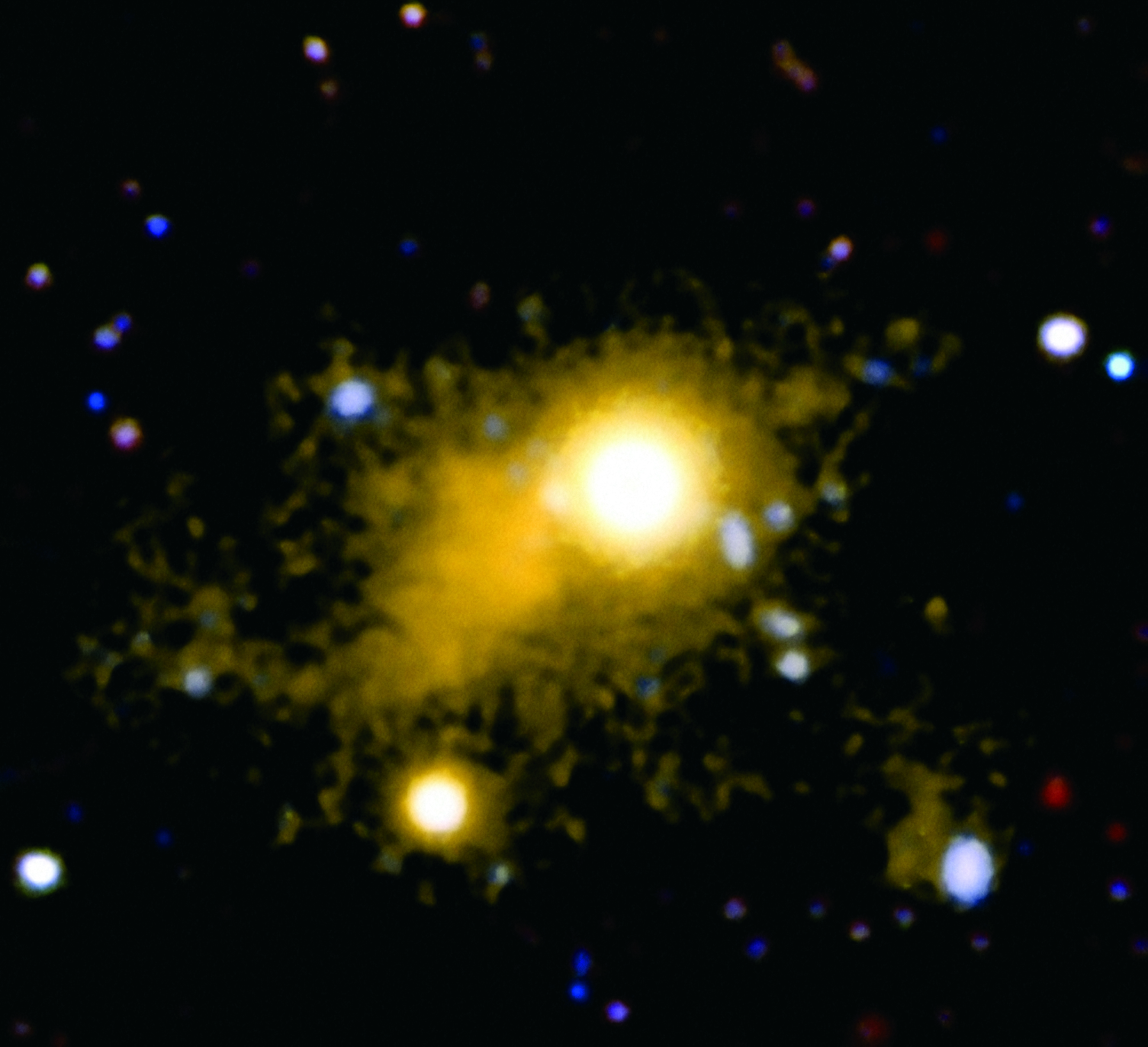

Cosmic Slug Sighting

When UC Santa Cruz astronomers caught strands of the “cosmic web” on camera, it was the first time anyone had glimpsed the intergalactic threads that were predicted to weave through the universe. The discovery was recognized by the editors of Physics World as one of the “top ten breakthroughs” of 2014.

“It’s a one-of-a-kind finding,” said J. Xavier Prochaska, principal investigator on the study. “But now we’ll look aggressively for more. our studies are forcing theorists to revisit their models.”

Computer simulations of the universe predicted that matter, such as galaxies, is distributed in a web-like configuration. But visible evidence for these predictions was missing. Prochaska’s team, which included UCSC astrophysicist Piero Madau, and former UCSC astronomer Sebastiano Cantalupo, provided that proof.

From the W. M. Keck observatory in Hawaii, the researchers took advantage of a quasar they found in a new nebula (now named the “Slug Nebula”). The quasar’s bright light illuminated the previously dark filamentary pattern of nearby gases.

Next year, the researchers plan to use a new camera, currently in fabrication at the UC observatories lab at UCSC, capable of capturing both images and spectra.

Four years ago, Prochaska’s research group garnered a top ten break-through from Physics World for discovering pristine gas and con- firming theories of the Big Bang.

Biomolecular Engineering

Single Cell Technology

A new nanobiopsy technique helps scientists peer into cells.

With a tip so tiny it can’t be seen with a microscope, a pipette engineered by UC Santa Cruz researchers is small enough to pierce a single living cell without causing any damage. The computer-automated technique, developed in Nader Pourmand’s multidisciplinary laboratory, Biosensors and Bioelectronics, was described in ACS Nano.

“We can now go in and sip a little content from a cell to see what it is doing, while it is doing it,” said Pourmand, professor of biomolecular engineering in the UC Santa Cruz Baskin School of Engineering.

This nanopipetting method makes it possible for researchers to regularly monitor individual cells. Measuring minuscule changes in cell contents, such as sugar levels, can mark a cell’s metabolic march from healthy to abnormal. The scientists also showed they can extract single organelles and measure RNa or DNa samples to discover which genes are being turned on or off at any given time.

“Until now we’ve been looking at endpoints of disease, but there’s a lot we’re missing in between,” Pourmand said. “This technique can help us get those details.”

For this work, Pourmand’s team became a finalist in “Follow That Cell,” a national NIH competition for novel solutions to study single cell dynamics.

Information Technology

Connected Community

More than a decade of legwork by UC Santa Cruz information technology specialists garnered a $10.6 million state grant to boost the fiberoptic highway for Internet connections south of Santa Cruz.

Those funds will help place 91 miles of data- carrying cable, from Santa Cruz to Soledad, to create a “backbone circuit” to back up lines if existing ones fail. The circuit will also offer more Internet provider access options for communities along the way.

“Education and research demand this kind of Internet capacity,” said Brad Smith, the UCSC director of research and faculty partnerships in Information Technology Services.

Smith and his colleagues scouted for efficient ways to add fiberoptic lines to existing structures or upcoming construction projects. once a route was identified, they teamed up with Sunesys, a telecommunication company that previously installed lines from the campus to Sunnyvale, and the Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California.

“The synergy of this project is nice,” said Smith. “We were able to use UCSC expertise to solve a university problem and benefit the community.”

The project is estimated to take two years and $13.3 million dollars to complete, Smith said.

Sea Star Scourge

For the past two years, sea stars along the Pacific coast have suffered catastrophic die-offs. The disappearance of these key predators could have profound effects on their tide pool and near-shore ecosystems.

In collaboration with UC Santa Cruz and other institutions, biologists at Cornell University identified a “sea star associated densovirus” as the most likely cause. Although the densovirus was a novel discovery for researchers, the infectious agent was found in museum specimens of sea stars collected in 1942. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The question is why a virus that’s been around for years went rogue, or whether environmental stressors made the sea stars more susceptible,” said Peter Raimondi, UCSC professor and chair of ecology and evolutionary biology. There may be good news, though.

“In the last six months, we’re seeing more sea star babies than we’ve seen in some places for the last 15 years,” said Raimondi, who leads the Pacific Rocky Intertidal Monitoring Program. “If the disease is gone, this new generation could replenish populations more quickly than expected.”

Marm Kilpatrick, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Melissa Miner, a research specialist at Long Marine Laboratory, also contributed to this study.

Linguistics

Native Tongue

Learning other languages can be difficult. So, when UC Santa Cruz linguists wanted to understand Irish Gaelic, they went straight to the source. To decode the complex language, the researchers make ultrasound videos of the tongue while native speakers form words. The project, “Collaborative Research: An Ultrasound Investigation of Irish Palatalization,” was awarded a $261,255 grant by the National Science Foundation.

Although Irish Gaelic is Ireland’s official language, it’s spoken by less than five percent of the population. One unusual aspect of the language is that every consonant can be pronounced two ways; either with the tongue raised and pushed forward, or raised and pulled back.

“It’s very difficult to describe what the tongue is doing without actually seeing it,” said Grant McGuire, an assistant professor in the Linguistics Department and co-investigator of the study. “Ultrasound allows us to see the tongue movement in real time.”

The precise tongue movements are documented by placing an ultrasound probe under the chin of native Irish speakers while they talk. So far, the team has studied 16 people from three regions of Ireland. Also on the project are linguistics professor Jaye Padgett, former UCSC grad student Ryan Bennett, and Irish colleague Máire Ní Chiosáin.

“We’re studying one endangered language. But this fieldwork teaches us more about the way all languages work,” McGuire said

Biomolecular Engineering

Reclassifying Cancer

Cancers are often categorized–and treated–according to where they are found in the body. But it may be more effective to base treatment on the molecular makeup of cancers, regardless of where they occur, according to a study published in Cell.

The same role can be played by cells in different parts of the body, explained Josh Stuart, a professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz and senior author on the paper. For example, cells that develop to form layers on surfaces may line the bladder, the throat, or other places. With similar origins, these cells may also share molecular pathways leading to cancer, and respond to the same treatments.

As part of the TCGA Pan-Cancer Initiative, a team from UCSC and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging led researchers to analyze data from 3,500 patients with 12 different cancer types. When the cancers were grouped by “cell of origin,” the data suggested that 10 percent of these cancers could be reclassified, potentially leading to different treatment options.

“This molecular information gives us a new kind of microscope to look at cancer,” said Stuart.

The researchers are now refining their results, analyzing 35 tumor types from 11,000 patient samples.

The UCSC-Buck team is led by Josh Stuart, David Haussler, the director of the UCSC Genomics Institute, and Christopher Benz, of the Buck Institute in California.

Sea Otter Supermoms

Once hunted to near extinction, sea otters on California’s Central Coast have made a comeback. But a stall in population recovery, with higher than expected deaths among female sea otters, prompted UC Santa Cruz marine biologist Nicole Thometz to investigate.

Thometz discovered the high-energy needs of pups may push their moms beyond their metabolic means. Her findings on “end lactation syndrome” were published in the Journal of Experimental Biology. The study was co-authored by Terrie Williams, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

Just to survive in a cold water habitat, these small marine mammals need to eat 25 percent of their body weight in food every day. “But we didn’t know how much more energy a mom needed to provide for her pup,” Thometz said.

To calculate the daily caloric needs of pups, from birth until six months of age, Thometz observed 26 wild sea otters to construct their daily activity budgets. Then, to determine the energetic cost of these activities, she recorded oxygen consumption during activities of seven young otters (in rehabilitation for release back into the wild) at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Thometz then estimated that moms had to double their energy intake when caring for a large pup. After pregnancy and nursing, females may be too energetically depleted to meet those demands without risking their own lives, she said.

“Sea otters are apex predators in the kelp forest. If we understand what impacts their population, we’ll understand more about our coastal ecosystems,” Thometz said.

Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology

Inheriting Memory

Studies have shown that parents can pass on memories of fear and famine to their children. But scientists don’t know how such experiences are handed down. A research team at UCSC demonstrated how “epigenetic” memory, created by changes in the way DNA is packaged in cells, could be inherited. The study was published in Science.

“We’re used to thinking about DNA sequences being passed from parent to child,” said Susan Strome, a professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology, who led the study. “Less clear is whether the way DNA is packaged can also be passed from parent to child, and through cell divisions.”

When DNA is tucked into each cell, the way DNA is wrapped affects whether genes are accessible to getting turned on or off. Histones are proteins that help wrap DNA. So, changes to histones may modify that packaging process and cause “epigenetic” effects, altering the expression of genes without changing the DNA itself.

In this study with roundworms, Strome’s lab chemically changed one specific histone marker in either an egg or sperm, and put a fluorescent tag on it. After fertilization (and commingling of the egg and sperm chromosomes), the bright tags persisted only on chromosomes that were direct DNA descendants of the altered egg or sperm. This showed how one “parent” could transmit epigenetic information to its offspring–a step toward elucidating mechanisms for more complex memory inheritance.

“The implications are profound for considering how environmental and nutritional conditions that parents experience could affect a child,” Strome said. “Those conditions may affect how DNA is packaged, and that can be inherited.”

People make pumas eat and run

Pumas don’t like hanging around human dwellings. That’s good news for people. But that aversion makes the big cats kill more often when they live near high-density housing, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. That behavior may affect local prey populations and the reproductive success of the pumas.

After a kill, mountain lions usually spend several days close to the carcass, eating their fill, explained Justine Smith, a Ph.D. candidate in the UC Santa Cruz Environmental Studies Department, and lead author on the study. “When humans are around, the animals leave their kill more often. That’s a lot of time and energy to give up, especially for females raising cubs,” she said.

The researchers followed 30 pumas that were outfitted with GPS monitoring collars, as part of the Santa Cruz Puma Project, led by Christopher Wilmers, associate professor of environmental studies. They found that females living in the highest housing density areas killed 36 percent more deer each year than females in more pristine habitats.

“We might be optimistic about results that show pumas can hunt successfully in a developed landscape,” said Smith. “But we know it takes substantial energy to hunt, and some of these females are killing a lot more.”

In a previous study, led by Terrie Williams, UCSC professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, researchers calculated the caloric cost of various hunting strategies–waiting, stalking, or pouncing. The results, published in Science, showed pumas save their high-calorie burning efforts for the bigger prey payoffs.

Psychology

Property and Power

The global rise of violence against women reflects inequalities in the structure of societies. In developing countries, where property confers power, women who own land are less likely to be victims of abuse, according to a study published in Psychology of Women Quarterly.

“Violence against women doesn’t start as an abusive relationship,” said Shelly Grabe, an associate professor of psychology at UC Santa Cruz who led the research. “The abuses of power start at a much higher level. If we want to eradicate abuse, we need to go back to those larger structural relationships. Of those larger relationships, land ownership is key.”

Grabe interviewed 492 women in Nicaragua and Tanzania. She gathered information that included their age, education, number of children, experience of violence, and land ownership. Her analysis suggested that shifting control over resources–land in particular–can dramatically change women’s lives.

One interviewee said: “Those times he used to beat you, he beats you because he knows you depend on him…But if he finds you have your own place, he can’t be able.”

“My data documents that we need to challenge the roots of abuse, rather than dealing with con-sequences,” said Grabe.

Rose Grace Grose and Anjali Dutt, graduate students in psychology, were co-authors on this study.

Feeling Blue

The National Endowment for the Arts awarded UC Santa Cruz a $45,000 grant to support “Blue Trail: Imagination and Innovation for Ocean Sustainability,” a series of interactive installations for the San Francisco waterfront.

The mascot for this project, “Oceanic Scales,” was inspired by the micro-organisms of the sea. Through an interactive digital art installation and game, the exhibit invites visitors to explore the role of phytoplankton in maintaining a balanced ocean ecology.

“Call it art. Call it science. Call it cultural curiosity,” said Jennifer Parker, associate professor of art, and founding director of OpenLab, UC Santa Cruz’s art-science research center. “We’re exploring how art can engage people to think differently about our natural environment.”

Blue Trail resulted from conversations among campus colleagues looking for new opportunities to encourage public awareness of the environmental crisis in our oceans. The physical creation of the Ocean Scales exhibit incorporates sustainable construction into the theme.

“OpenLab develops work for experiencing art and science research that is accessible to the general public,” Parker said.

UC Santa Cruz was one of 886 non-profit organizations to receive an Art Works grant.

Psychology

Dance Moves

The phrase “going through the motions” implies laziness or lack of interest. But elite dancers often substitute hand motions for full body movements while they learn demanding dance routines. This practice, called “marking,” may improve the quality of the finished performance, according to a study published in Psychological Science.

“Marking is an unusual cognitive device that we see in other areas. Basketball players use it to create muscle memory for free throws,” said Ted Warburton, a professor of theater arts at UC Santa Cruz. “But in dance, it’s more than a form of mental rehearsal. It’s a unique tool that makes a mental connection to an action, but also can enhance the quality and expression of that action.”

In this study, 38 advanced ballet students were divided into two groups to learn a basic routine. Judges awarded higher scores, for execution and artistic expression, to performances given by dancers who were allowed to mark during rehearsal. This technique may spare strain on the bodies and minds of dancers, said Warburton. But it might also be useful in other learning situations.

Co-authors on the study included Margaret Wilson, a UCSC associate professor of psychology.

Geophysics

Fault Finding

The seafloor jumped about half the length of a football field when a magnitude-9 earthquake hit Japan in 2011, trig-gering a devastating tsunami and surprising scientists. “That’s the largest slip recorded–ever. The question was: Why?” said Emily Brodsky, a UC Santa Cruz geophysicist and co-author of three papers about the Tohoku-Oki earthquake published in Science.

The answer was in the temperature of the rocks beneath the sea. During earthquakes, tectonic plates generate friction when they grind against each other. High levels of friction create intense heat that takes several years to dissipate from rock. Those frictional forces can be calculated from temperature measurements, explained Patrick Fulton, a UCSC seismologist on the heat-seeking mission.

The UCSC scientists joined an international research team to get core samples from the fault zone. Then, they strung 55 temperature sensors across the fault to measure the background heat. Their findings: Three-tenths of a degree of excess temperature remained at the fault.

“That small change tells us the friction was very low, making that huge slip possible,” said Fulton.

Results from the two other Science papers showed a layer of clay at the fault zone also contributed to the slippery site.

Next, the researchers plan to take temperature measurements from other earthquakes to see if low readings always correspond to big jolts.