Border Crossings

Artist John Jota Leaños creates animated documentaries to reveal hidden stories

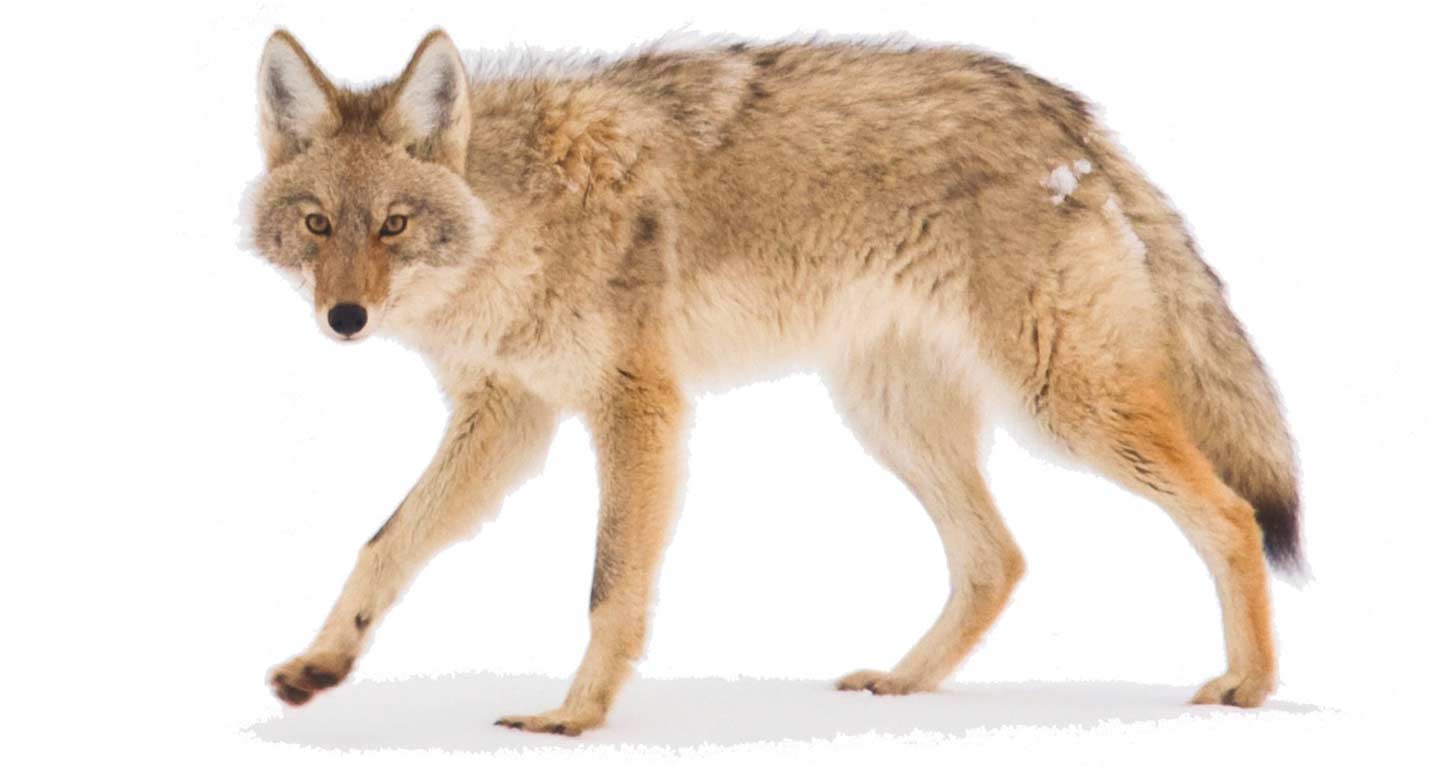

Coyote has a chorus of meanings: For many indigenous tribes, the animal represents a trickster figure; in the Southwest, it’s someone who is culturally and ethnically mixed, who passes as both Latina/o and white; and it refers to people who smuggle immigrants across the Mexico-U.S. border.

All these interpretations apply, more or less, to artist John Jota Leaños, a Guggenheim Fellow and an associate professor of social documentation at UC Santa Cruz.

Leaños claims membership in the playfully self-named tribe Los Mixtupos (emphasis on mixt-up). His dad is Mexican-American, his mom Italian-American, and he’s a California native. He enjoys the political-multicultural term Xican@, the equivalent of Chicano/Chicana–although he sometimes quasi-mockingly calls himself a gringo. In other words, Leaños embraces complexity in his life–and in his art.

Of course he doesn’t physically smuggle people, but he does try to slip ideas–political, dissenting, alternate–across mental borders. Willing to use any art form to counter mainstream media, documentary animation is his central method for sharing previously untold stories. Adding dark humor to his multimedia approach, Leaños’ narratives entice people to consider different perspectives.

“Documentary animation is very rich for telling alternate stories that are complex and multivocal,” he said.

Leaños trains students in this increasingly important tool through UCSC’s Social Documentation graduate program, part of the Film and Digital Media Department.

Animation has been a staple of serious filmmaking since it was first used in a 1918 documentary about the sinking of the Lusitania. It can recreate scenes when no footage exists and convey concepts, scientific and otherwise, that are difficult to describe in words.

Leaños has found it to be a powerful device for rendering multilayered stories. In his most recent film, Frontera! Revolt and Rebellion on the Rio Grande, 16th- and 17th-century animated characters leap to life–fighting, dancing, and performing spiritual ceremonies. The tale begins with the mythical horned serpent of thunder and lightning slithering out of the sky and disappearing into the Rio Grande, starting a new round of drought and violence. Infographic maps erupt in flames at hotspots, exposing the reach of indigenous unrest in colonial Mexico leading up to the successful Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

This history still lives, Leaños said, in the New Mexico and Arizona Pueblos that have sovereignty today as a result of that revolt. He reinforces the connection between past and present by relying on the voices of modern-day Pueblo people in Frontera!

In one sequence, an ani-mated narrator sits among the slot machines in the City of Gold Casino, wittily recounting oral history: “To this day, it is said that the first white man the Pueblo people encountered was black….” This black man, Esteban, was probably a Moroccan Moor and slave, one of four who survived a 1528 Spanish expedition to the New World. Their rumors about the “seven cities of gold” brought the conquistadors–portrayed by Leaños as drooling cartoon characters–north from New Spain into the Pueblo homeland.

Esteban’s legacy, says the narrator, “is one of confusion in the borderlands, where blood is still being spilled.” Then the windows of her slot machine scroll through present-day images: armed border guards, a starving man traversing the desert, and crosses for graves.

“I look for ways to tactically engage my audience, especially the Native and Latino communities,” he said. “I’m not trying to keep something from people intentionally, but having certain cultural knowledge may unlock a layer of perception and meaning, like gaining access to a new level in a video game. It’s a tactic of flipping the script on the white-dominated media.”

Despite the serious content, Leaños employs pop-culture design and appealing approaches.

The film’s visuals are mestizo–mixed–everything from comic-book “bam-pow” style to spare, beautiful charcoal renderings. There is humor, too. Conquistadors and missionaries wear sunglasses and rapper-like bling. And there’s hip-hop: Leaños’ trilingual song recounts how drought, hunger, the prohibition of Native religion, and systematic atrocities committed against the Pueblos by the colonial government, soldiers and priests, all provoked the communities to rebellion.

They drove the Spanish occupiers from the Rio Grande region and reclaimed their ceremonies and culture–a respite from foreign rule that lasted for 12 years.

This account of struggle and victory is “enthralling,” declared the Latin Post, an English media site. Both PBS.org and Latino Public Broadcasting presented Frontera! during National Hispanic Heritage Month in September 2014. The documentary won “Best Animation” at the 39th Annual American Indian Film Festival and “Best Short Film” at the XicanIndie Film Fest.

With funding from his Guggenheim Fellowship, a United States Artist Award, and other awards, Leaños spent two years on research, collaborating with indigenous archeologists, history keepers and artists.

“Representation remains at the core,” he said. “You start with the question: How do we represent this culture, this character, this idea?” To get those answers, he worked with Native, mestizo and Chicano/a partners in New Mexico and the San Francisco Bay Area.

“The stories, imagery and perspectives of the Pueblo people were central to the project,” said one of the film’s producers, Aimee Villarreal, an anthropologist (UCSC Ph.D. ‘14) and assistant professor of Comparative Mexican American Studies at Our Lady of the Lake University in Texas. The documentary’s positive reception in Native American and Chicana/o communities showed “that we were successful in our attempt to produce a film that animates the spirit of activism and solidarity that is at the heart of this story,” she said.

Figuring out what to include in the film took time because it was a 20-minute piece, not a 500-page book. “As an academic, I’m always thinking about how can I integrate complexities in a short time-based piece. There are layers of stories, academic research and oral histories in Frontera!” Leaños said.

One of the intricacies the team dealt with was how to convey the violence of the events without making it too cartoonish. “Certain Pueblo consultants told us that we needed to illustrate the violence in order to depict what communities suffered and why they took desperate means to alleviate and decolonize their lives,” Leaños said. “However, we had much internal debate about this. Should we not show violence? How do we represent it?”

These lesser-known episodes from the past matter, Leaños said. Remembering the Revolt, considered the first American Revolution by the Pueblo peoples, gives them a sense of power. Forgetting it lets the dominant culture glorify conquistadors like Onate, who killed 800 Acoma people in 1599, enslaved surviving women, and cut off one foot from captured men.

Continuing to explore the ideas of the frontier, colonization and resistance, Leaños’ next research project is a sequel of sorts, called Eureka!

“We all know the story of the California Gold Rush, right? But we don’t,” he added with a smile.

This new animation will focus not just on the Gold Rush at John Sutter’s mill, but also on the Taos Revolt in 1847. Both events took place on land annexed from Mexico during the Mexican-American War. According to Leaños’ research, Sutter and the American rulers of the New Mexico territory treated the indigenous people brutally. “When you go to Fort Sutter, you hear nothing of that. It tells only a snippet of the story,” Leaños said.

“It is the poverty of knowledge and perspectives that gives me impetus to tell stories this way”–full of complexity and coyote humor.