Guided by the light

Stars bring biology into focus

When we look at the stars, we often marvel at the vast universe surrounding us. Joel Kubby, UC Santa Cruz professor of electrical engineering, saw a tool that could help scientists understand cell biology.

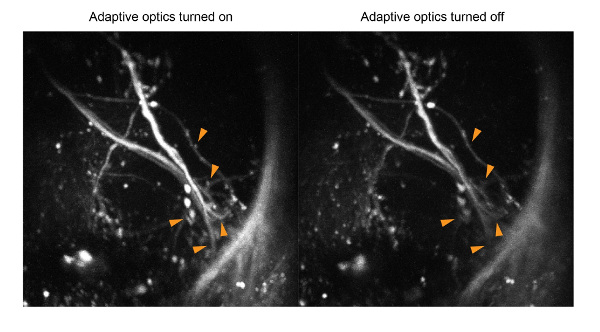

Neuroscientists use microscopes to study cells in living tissues. However, simple light microscopes—like those found in high school classrooms—don’t provide enough contrast to see cellular details. This task requires fluorescence microscopes, instruments that capture light from molecular probes that glow when they’re added to cells. But even with these beacons, overlying tissues can obscure the cells deep within, for example, the brain of a fruit fly.

In the early 2000s, engineers started using adaptive optics, a technique developed for astronomy, to improve fluorescence microscopy. The swirling gases in our atmosphere blur the light coming from celestial objects, just like biological tissues blur fluorescence coming from cells. Kubby noticed these efforts employed a different method than the one used in astronomy. “I thought it’d be interesting to take a look at why,” he said.

The astronomy method first measures how the light from galaxies and planets gets distorted. It does this by focusing on a “guide star,” either a nearby star or a spot generated by a yellow laser pointed into the sky. Then the adaptive optics system bounces the reference starlight off small mirrors that rapidly deform to erase its distortions. When the guide star comes into crisp focus, it brings a clearer image of its celestial neighbors with it.

In cells, however, there are no stars. Adaptive optics systems for microscopy estimated the biological light distortion, allowing viewers to adjust the light until the image became clear, like finding the best sound with a radio dial. Knowing how well the guide-star method worked for astronomy, Kubby decided to adapt it for microscopy.

“Joel is one of the early pioneers,” said Na Ji, UC Berkeley associate professor of physics and neuroscience. “He is the first person to use the measurement that was developed for astronomy in microscopy.”

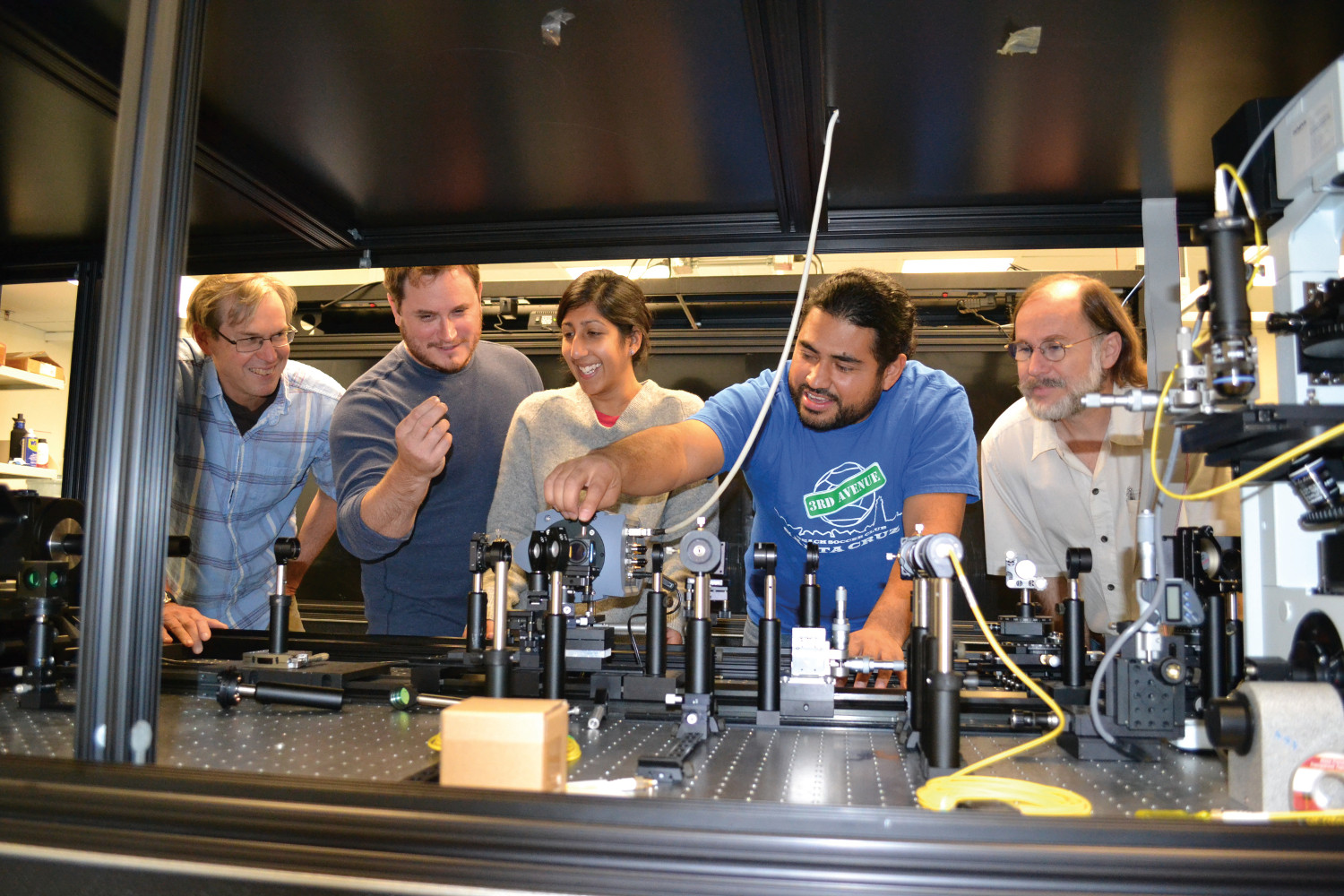

In his system, Kubby uses fluorescent regions in tissues as guide stars. He first illuminates a tiny point in a fluorescently labeled sample so that it glows, and then corrects it into a perfect circle with adaptive optics to clarify the image of the target tissue. Faster than the radio-dial system, Kubby’s system is now being used by many researchers, including Ji, particularly with live samples that are rapidly changing. It may also open new areas of research by unveiling previously hidden cellular physiology. At UCSC, Kubby and team are planning to explore what happens when neurons in the brain misfire, like during epilepsy or Parkinson’s disease.

Although his system is still limited to use by engineers who are microscopy experts, Kubby hopes it will become ubiquitous as more biologists see how it can improve their imaging studies. He sees a future where adaptive optics is a standard feature on fluorescence microscopes. “You just press your ‘AO button’ and there it is,” he said.