Brief inquiries

Economics

Preparing for recession

During the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve reinvigorated the economy by slashing its benchmark interest rate to zero. Today, as the economy continues to rebound, interest rates are climbing.

But due to shifts in the global economy—in particular, the emergence of China—economists expect slower growth and interest rates to remain low overall. If there’s another financial crisis, inflation will again plummet, taking interest rates down with it.

With rates already low, the Fed won’t be able to cut them further to spur spending. “When interest rates hit an effective lower bound, monetary policy is constrained in its ability to help stabilize the economy,” said Carl Walsh, distinguished professor of economics.

Other safeguards may be needed. Walsh and other economists are evaluating whether central banks should move away from current policies that work to maintain a certain inflation rate. They could instead aim to keep general prices at a certain level or promise to keep future interest rates low. Such forward guidance policies are discussed in a new chapter in the recently published fourth edition of Walsh’s textbook, Monetary Theory and Policy.

If and when another recession hits, investors would expect these price-level targeting policies to bump prices—and inflation—back up, Walsh said. The anticipation of higher inflation coupled with rock-bottom interest rates would incentivize people to borrow and spend, thus stabilizing the economy.

Sociology

Big data for kids

“Imagine you’re a school principal with a struggling student and you have no information about what’s going on,” said Rebecca London, assistant professor of sociology and research liaison to the Silicon Valley Regional Data Trust (SVRDT).

Substantial information about health, living situation, and other social factors—which contribute in major ways to school performance—resides in public agency databases, said Rodney Ogawa, research professor of education and a SVRDT director. However, because each agency’s data are isolated, they’re unavailable to outside educators and health and human service workers trying to help children. The SVRDT aims to change that, Ogawa said, while safeguarding students’ privacy.

Working with San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz county child welfare services, Offices of Education, juvenile probation, and behavioral health staff, the SVRDT has nearly completed a prototype Internet “portal” that will allow authorized individuals—including teachers, social workers, policymakers, and UC Santa Cruz researchers—to access certain student information. Made possible by recent California legislation, the “big data” sharing collaboration so far includes information about some 265,000 students.

“We expected some hesitation, but everyone said ‘yes, we need this,’” Ogawa said, “This is ultimately for the kids and families of Silicon Valley, particularly those at risk for poor outcomes. That’s what’s driving us.”

Earth and Planetary Sciences

Sedimentary climate clues

To what extent has human activity contributed to today’s powerful storms and heat waves? To help answer this key climate change question, James Zachos, professor and chair of Earth and planetary sciences, looks to the past.

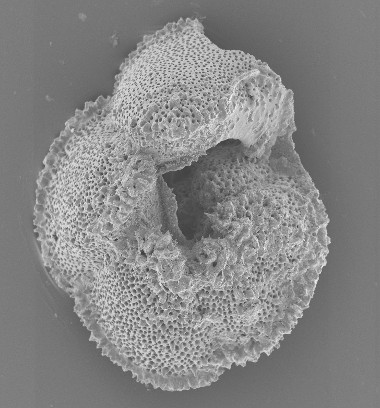

Fifty-six million years ago, during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), the Earth heated up 6° C and stayed warm for 150 thousand years. In a recently published study, senior author Zachos and collaborators analyzed ancient plankton shells from this period to reveal increasing ocean salinity and temperature. By producing greater evaporation near the equator, these changes would likely have led to more intense storms at higher latitudes and poleward shifts in dry and wet regions.

Although the heating during the PETM didn’t occur nearly as fast as today’s human-caused climate change, such case studies can be used to inform theories about how global warming will impact future hydrology. In California, for example, Zachos’s work supports models that predict more severe droughts and storms.

“We’re basically doing forensics,” said Zachos, who has been studying ancient ocean sediments for 30 years. “CO2 levels are going to go up, and climate specialists want to accurately predict how that will impact things like precipitation, so communities can plan.”

Mollecular, cell and developmental biology

Stiffing cancer

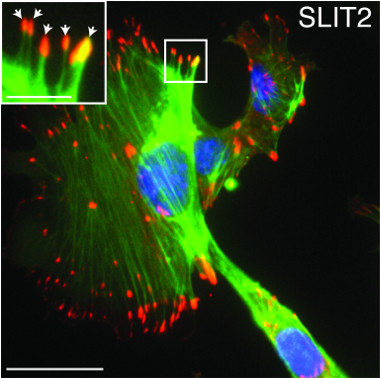

Within the body’s tissues, a framework of molecules called the extracellular matrix (ECM) holds cells together. As tumors develop in many types of cancer, this framework stiffens.

“A lump felt during a monthly breast exam does not necessarily reflect the number of cancer cells,” said Lindsay Hinck, professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology. “It reflects both the cancer cells and the stiffened extracellular matrix.”

ECM stiffening appears to block cancer progression by maintaining a balanced state, or homeostasis, of intracellular tension. Conversely, loss of this homeostasis can contribute to cancer progression by promoting tissue disorganization and metastasis.

Hinck’s research focuses on understanding this complex biology. Senior author Hinck and collaborators now report that normal breast epithelial cells sense and respond to increased ECM stiffness by reducing levels of the microRNA miR-203, a short, noncoding RNA fragment that normally suppresses the Robo1 gene. This raises levels of the protein ROBO1, which, in turn, alters the cell’s cytoskeleton and boosts production of adhesion molecules, changes that help cells retain their shape and position within the stiffened ECM. The investigators also found that breast cancer patients with low-miR-203/high-ROBO1–expressing tumors had improved survival, identifying this pathway as a potential therapeutic target.

Linguistics

Lost languages

The task of saving indigenous languages has acquired increased urgency as more and more are threatened by emigration, rapid cultural changes, and the failure to teach native tongues to children.

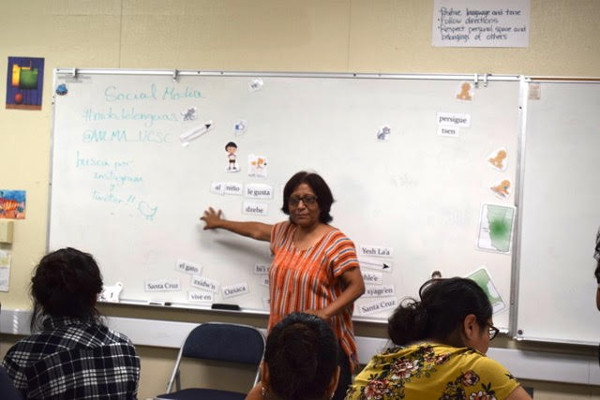

Associate professor of linguistics Maziar Toosarvandani stands on the forefront of this effort. To preserve their rapidly disappearing language, Toosarvandani partnered with Northern Paiute speaking elders near Mono Lake—of whom only a handful remain. He’s now taken on the Santiago Laxopa variety of Zapotec, an endangered native language from Oaxaca, Mexico. Of the 100,000 Oaxacan immigrants who live in communities across California, including Santa Cruz, nearly all speak Spanish. Fortunately, some also speak Zapotec.

In their research, Toosarvandani and his team collect stories, oral narratives, and historical texts from which they infer the structure of the language. Then, by speaking Zapotec with native speakers, they test their hypotheses about its structure and collate their findings in an open access database integrated with a dictionary.

Toosarvandani and his colleague, associate professor of linguistics Pranav Anand, have also partnered with the organization Senderos to establish Nido de Lenguas, a nonprofit that sponsors monthly language classes and summer camps where native speakers teach their ancestral language to other Oaxacan immigrants. This work is vital, Toosarvandani said. “When we lose a language, we lose an aspect of what it means to be human. If we’re interested in saving the world’s diversity, we should be interested in saving these languages.”

Computational media

Connecting the dots

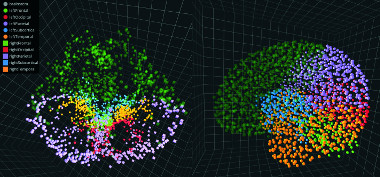

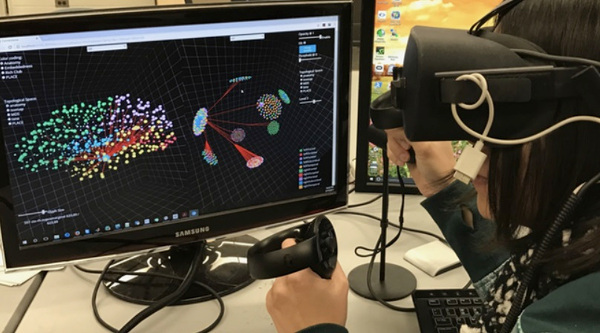

Widely used by clinicians for decades, noninvasive neuroimaging techniques such as CT, MRI, and PET have also enabled neuroscientists to explore structural and functional networks, or “connectomes,” in the brain. Critical to this research are tools for effectively visualizing and interpreting the great mass of data generated by these imaging modalities.

A common task in studying neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease involves comparing the connectomes of healthy and diseased groups to identify brain changes due to illness. However, no application existed that allowed robust comparisons in real-time of two or more connectome datasets.

To address this need, UC Santa Cruz researchers, working with collaborators at the University of Illinois, Chicago, built the first system for 3D visualization of multiple connectome datasets via a synchronized side-by-side layout. Brain researchers and clinicians can access the system, NeuroCave, via a standard desktop environment or, for a more immersive experience, portable VR headsets.

“The ultimate goal is for a psychiatrist or neurologist to do precision medicine by using NeuroCave to compare a patient’s connectome with the average connectome for any number of diseases,” said Angus Forbes, assistant professor of computational media and senior author on the paper describing the tool.

Astronomy and astrophysics

Flash in the sky

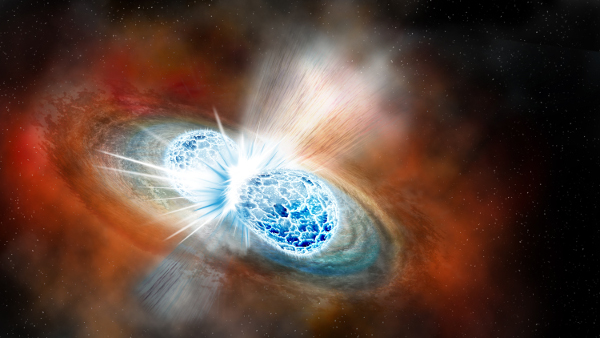

Assistant professor of astronomy Ryan Foley was enjoying an afternoon off in Copenhagen when a student texted him. LIGO, the Laser-Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory—which had previously detected ripples in the fabric of space-time for the first time, garnering fanfare and a Nobel Prize—had found another gravitational-wave signal.

This time, the signal likely came from merging neutron stars—exotic, city-sized objects with the mass of one or two suns. And unlike previous detections, this cosmic crash was expected to light up.

Astronomers around the world raced to find that flash of light. Just 17 minutes into their search using the Swope Telescope at the Carnegie Institution’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, Foley and his team found it: a bright dot in a galaxy 130 million light-years away. Their and others’ observations were quickly published in multiple papers in Science, Nature, and Astrophysical Journal Letters.

It was the first time anyone measured the light from an event that also produced gravitational waves. The observations revealed that these mergers could have produced most of the elements heavier than iron in the universe. This kind of measurement also provides a new way to probe the expansion rate of the cosmos—crucial for understanding deep questions like the nature of dark energy, Foley said. “It’s really just the beginning of a new scientific field.”

Literature

A traveling memory space

How did history’s first ghetto affect Western culture and Jewish identity? That’s what Murray Baumgarten, distinguished professor emeritus of English and comparative literature, seeks to understand.

Created to impose surveillance and control while also allowing a measure of autonomy, the Venice Ghetto is a walled-off section of the city in which Jews were forced to live from 1516 until 1870.

“The Venice Ghetto shaped how many Jews and Jewish communities think of themselves in relation to their outside social situation,” said Baumgarten, whose research has focused on how its impacts are described in both fiction and nonfiction writing, such as Coryat’s Crudities, a travelogue published in 1611.

Baumgarten brings this insight to his current study of the writing of Primo Levi, an Italian chemist and Holocaust survivor. Describing Levi’s book The Periodic Table (1975) in a recent essay, Baumgarten writes, “…Primo Levi, writer, is inseparable from Primo Levi, Holocaust witness, and the discourses of science and art are subtly intertwined and reciprocally illuminating.”

“You have to look in many places, because this space has traveled, and it is also a memory space,” said Baumgarten. “It’s also a space of trauma that has changed many things.”

Ecology and evolutionary biology

Resilience under redwoods

There’s more to redwood forests than iconic trees. On the drought-prone Central Coast, the forest understory includes a typically tropical resident—ferns.

Jarmila Pittermann, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Emily Burns of Save the Redwoods League, noticed that during persistent drought, ferns’ fronds dry out and often become infested with tiny insects called thrips. To unveil drought’s physiological effects and how the ferns recover during rainy spells, Pittermann’s team studied the region’s two most abundant species of fern, Polystichum munitum and Dryopteris arguta, comparing ferns growing in the forests surrounding UCSC to potted, greenhouse specimens that they periodically dried out and rehydrated.

As reported in New Phytologist, the ferns were surprisingly resilient, but didn’t produce many fronds when it was particularly dry. Doing so would cause them to “consume their supply of water and carbohydrates too fast,” Pittermann said. The ferns can also rehydrate quickly, taking up water—including from fog—directly from their fronds, as previously shown by Burns.

“People think of ferns as inferior to angiosperms and conifers, and that’s untrue,” Pittermann said. “Ferns are holding themselves up. They have had to be resistant to make it through 350 million years of our changing planet.”

Psychology

Race in schools

Students who feel they belong perform better. And when students feel stereotyped in school, their academic performance suffers. Years of sociological research bear this out. But there are other, subtler elements that can contribute to a school’s racial climate and impact student outcomes.

“The biggest surprise was how understudied some of these factors are,” especially the negative outcomes when racial differences are simply ignored, said Christy Byrd, assistant professor of psychology.

Byrd studies how students perceive their school environment in relation to their racial and cultural identities. Her survey of adolescent students led to a new framework that combines a wide variety of factors impacting students’ sense of belonging.

“It’s about how they all fit together,” said Byrd, who hopes her framework will inform future research. The most influential factors included the quality of interactions between racial groups, whether students felt they were treated fairly, and if there were opportunities to learn about other cultures, prejudice, and racial inequality.

Her work also shows that students with a strong sense of belonging in their school’s racial climate felt more motivated compared to students who believed their racial identities were represented negatively or not at all. And crucially, strong intrinsic motivation correlated closely with academic engagement and success.

Chemistry and biochemistry

Beneficial binding

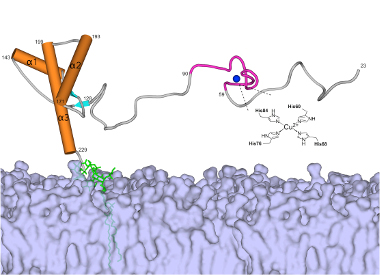

Prion diseases, including mad cow and, in humans, Creutzfeldt-Jakob, are fatal neurodegenerative diseases. They arise, usually late in life, from massive aggregations of endogenous prion proteins.

Compared to the hallmark aggregating proteins of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, “the prion protein is quite complex,” said Glenn Millhauser, distinguished professor of chemistry. “Its multiple domains with all sorts of chemical modifications point toward an important function in the central nervous system.”

The bulky end of the prion protein binds to the surface of neurons where it modulates the flow of chemical messengers. Research has also shown that the extended, flexible end, in an unfolded configuration, drives prion toxicity and neuronal death.

Millhauser has been studying the prion protein structure for two decades. Of particular interest to him is how the protein binds copper ions. Scientists believe the protein binds copper to regulate the metal ion, which is essential for cellular function but extremely toxic if left unbound. Based on nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Millhauser and collaborators have now reported that copper, in turn, also regulates the prion protein by forcing its extended end to fold inward, thereby keeping its disease-related activity in check.

Electrical engineering

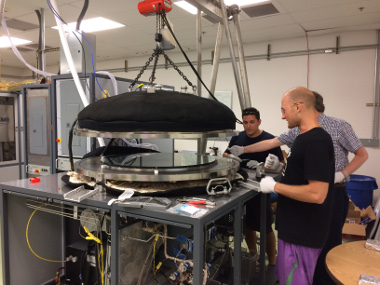

New coats for telescopes

Silver makes better telescope mirrors. It reflects more visible and infrared light than aluminum, the metal most telescope mirrors are made from. But while aluminum forms a natural protective layer when exposed to air, silver doesn’t—that’s why it tarnishes.

To combat this degradation, telescope makers coat the silver with a protective layer using physical vapor deposition, spraying, for instance, aluminum oxide vapor onto the silver. Even so, the mirrors still corrode after a couple years.

The problem is that this coating method leaves pinhole-like gaps. “All kinds of stuff—oxygen, water, sulfur—those elements go through the pinholes to reach the silver,” said Nobby Kobayashi, professor of electrical engineering.

With collaborators UC Observatories astronomers Andrew Phillips and Michael Bolte, UCSC postdoc David Fryauf, and Structured Materials Industries (SMI), Kobayashi designed a new instrument that employs atomic layer deposition (ALD) to coat the silver. Widely used in making semiconductor chips, ALD creates a dense, even film by coating surfaces one atomic layer at a time.

Because ALD systems are designed for small, thin silicon wafers, the researchers had to build a much larger one to accommodate telescope mirrors. While the prototype is still being tested, proof-of-principle experiments have shown promising results, Kobayashi said.

Music

Gender equality via music

Women stand at the forefront of music in Uzbekistan, a stature rooted in the hujum, a Soviet-era women’s emancipation movement. Women went free of culturally sanctioned, modest attire, and, through music, found “a natural space at the table in the state music conservatory and other institutions,” said Tanya Merchant, associate professor of music.

Merchant’s 2015 book, Women Musicians of Uzbekistan: From Courtyard to Conservatory, draws on her almost 20 years of studying Uzbek music. Her research focuses on the female artists who have contributed to modern Uzbek music, many of whom play the Uzbek dutor (also spelled dutar). A two-stringed lute, the dutor is the only non-percussive instrument traditionally played by women. Because of this, after the fall of the Soviet Union, women continued their prominence with the instrument, rising to positions of power rare in any patriarchal society.

Unfortunately, the current political climate and travel bans make it difficult for Merchant to bring dutor teachers from Uzbekistan to help “immerse” her students in Uzbek musical practices. “Ethnomusicology isn’t about sitting down, listening to sounds, and making assertions,” Merchant said. “It’s best to be embedded in the culture.”

Computer science

Bringing storage up to speed

Storage systems—the software that connects an electronic device’s applications to its disk or solid-state drives—have lagged behind other improvements in computer systems. New applications normally add layers of software to get what they want from storage systems, leading to bloated software and inefficiency.

“Storage systems are complicated and they slow things down,” said Carlos Maltzahn, professor of computer science and director of the Center for Research in Open Source Software (CROSS).

To address this problem, the CROSS team created a uniquely programmable storage system based on Ceph, a widely used, open source storage system also created at UC Santa Cruz. Called Malacology (after the science of molluscs: cephalopod molluscs, like octopi, are agile and have many arms moving in parallel), the new storage system lets programmers tap into existing storage system software and adapt it for new purposes, while retaining code that took years to optimize. The group published their work at the EuroSys 2017 conference.

“Open source software community efforts are allowing innovation to flow much more freely and appear much more quickly on the market than proprietary solutions,” said Maltzahn. He thinks Malacology will help enable innovation and entrepreneurship, ultimately leading to improved computers, smartphones, and other digital technology.

Environmental studies

A dwindling wellspring

During Peru’s long dry season, seasonal glacier melt releases sorely needed water from frozen storage. The warming climate initially increased the flow, boosting agriculture and hydroelectric power. But Andean glaciers have continued to shrink, and so has the water supply.

“It’s much farther along than we thought,” said Jeffrey Bury, professor of environmental studies and faculty director of the Center for Integrated Spatial Research. Bury’s research focuses on how glacier loss and social factors impact access to water in Peru, from its high mountains to its coastal cities.

Bury and collaborators now report that the Cuchillacocha glacier is shrinking 37% faster than previously predicted. Streams and wells have dried up, forcing people to travel, build new infrastructure, or relocate to find water. In addition, heavy metals from bedrock exposed by the receding glacier and the area’s long history of mining have contaminated mountain streams.

“The scale of these changes is astounding,” Bury said. Demand is growing, with cultivation of profitable, water-intensive crops for export on the rise, and expanding cities consuming more clean water and power. “There will be a point when supply won’t meet demand,” he said. “It’s just a matter of time.”