Genes to go

Genome sequencing leaves the lab with handheld device

Advances in genome sequencing technologies have led to an explosion of genetic data—collected from fruit flies to woolly mammoth fossils—at an increasingly affordable cost. Over the next ten years, several companies plan to sequence human genomes by the millions. Buried inside the genetic information of any organism, its genome, are clues to health, inter-species relatedness, and, in some cases, susceptibility to disease. One misplaced building block, or portions of genes that have been deleted or relocated in the genome, could trigger drug resistance, cancerous changes, or disease.

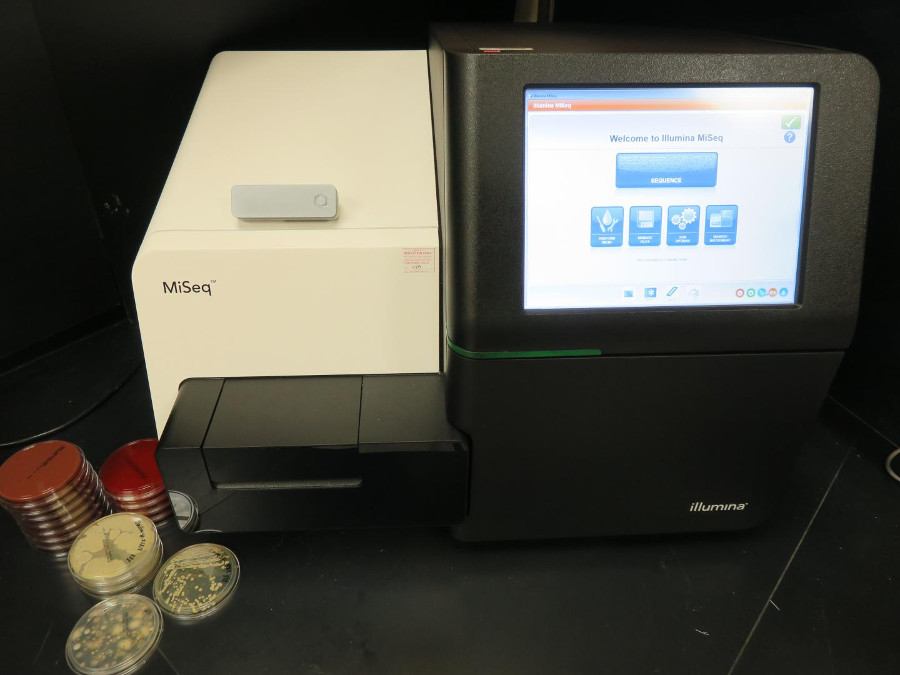

Typically, specially trained scientists operate sequencing machines, each about the size of dorm room refrigerators, at dedicated centers. Now, a candy bar–sized commercial device called MinION, which incorporates a novel method of DNA sequencing developed at UC Santa Cruz, is making the process more rapid, portable, affordable, and accessible than ever before.

Inside a MinION, the controlled movement of DNA through a protein pore generates electrical signals that can be interpreted into genetic information within minutes of starting sequencing. With the fast results from this nanopore sequencing, scientists can quickly identify infectious bacteria or follow the spread of viral outbreaks. Dozens of MinIONS have hit the road, tucked into scientists' backpacks to identify frogs in Tanzanian jungles, or packed along with medical gear to study malaria in India; they've even been used to identify microbes on Arctic glaciers and the International Space Station.

Although nanopore sequencing is accumulating a record of success, during its development the UC Santa Cruz researchers faced skepticism from their colleagues. "Not long ago, people still didn't believe that it worked," said Mark Akeson, professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

Reading a genetic code

In the world of DNA sequencing technologies, the MinION is unique because it uses nanopores to directly detect a DNA sequence. More commonly, sequencers re-create the genetic coding by building a new strand of DNA on top of an existing strand.

The first method of DNA sequencing, developed by Frederick Sanger in the 1970s, mimicked how cells naturally copy DNA. During this process, proteins unzip a DNA helix, revealing the sequence of building blocks—the bases A, T, G, and C—on each strand. Another protein slides along one strand, identifying each base and pairing it with its partner, A with T, and G with C. Every so often, the protein adds a base carrying a molecular identification tag, which stops that strand from growing longer. Then researchers separate the newly synthesized strands by length, and determine the sequence by reading the tagged bases at the end of the strands in order from shortest strand to longest.

Two large teams of researchers, including UC Santa Cruz scientists, used the most advanced Sanger sequencing machines to generate the first publicly available draft of the human genome, part of a decade-long effort that produced a finished sequence in 2003. During that time, computer scientists at UC Santa Cruz also developed the web-based Genome Browser as a tool to visualize and explore the three billion bases of the human genome. Today, the Genome Browser also contains genomes of animals, fish, and common research organisms such as mice, rats, worms, and yeast.

Over the past decade, improvements in technologies have led to machines that can sequence the human genome in a few days. These machines process 100 to 1000 times more DNA in each run than the best Sanger sequencers. The increased throughput means the machines need only a few days to sequence a genome up to 30 times to ensure that the order is accurate.

In addition to processing large amounts of DNA at the same time, the MinION has an added speed advantage: It delivers a complete viral genome sequence within minutes of a strand slipping through a nanopore.

"There's no field in science right now that's accelerating in terms of throughput and cost reduction anything like DNA sequencing," Akeson said, noting that one company offers to sequence entire human genomes for $1000. "Companies are competing with each other aggressively, and the public gets benefit out of that."

Through the nanopore

David Deamer, biomolecular engineering research professor at UC Santa Cruz, first imagined nanopore sequencing in the middle of a road trip, pulling off the highway to scribble down his ideas. At the time, he was at UC Davis making pores in cell membranes trying, with his then-postdoctoral associate Mark Akeson, to create openings that would allow the building blocks of DNA, and its chemical cousin RNA, to slip inside.

If a pore could let the building blocks of DNA slip through, Deamer reasoned it might allow an entire DNA strand to pass through as well. Applying a positive charge to the inside of the membrane would attract negatively-charged DNA, drawing it through the pore along with additional ions. He imagined that structural differences of each base in DNA would impact the ionic flow in ways that caused a unique electrical signal for each base as it moved through the pore. Deamer started testing the idea in the lab, continuing experiments with nanopore sequencing when he moved to UC Santa Cruz in 1994. Akeson joined him on the faculty a few years later.

One challenge in developing nanopore sequencing was controlling the speed of the DNA as it moved through the pore. Akeson and his students wanted to guide DNA through the pore one base at a time using a ratchet-like protein attached to the top of the pore. However, the first few proteins they tried only briefly grabbed DNA before letting it pass through the pore. Then the researchers tried an enzyme called phi29 DNA polymerase. It held on 40,000 times longer than the others—enough time to detect signals from single bases inside the pore. For Akeson, that result remains a highlight in his 20 years of improving nanopore sequencing.

Anyone, anything, anywhere

In 2007, the executives of a company called Oxford Nanopore, based in the UK, visited Deamer and Akeson with a mockup of a handheld nanopore sequencer. Akeson and Deamer were surprised: "We thought that it would work, but we didn't think it could be that small," Akeson said.

With their tiny device, the founders of Oxford Nanopore—nanopore scientist Hagan Bayley and biotech executives Gordon Sanghera and Spike Willcocks—chased a large goal: to produce DNA sequencers that anyone could use, anywhere, to sequence genetic information from anything. In 2014, the company released the MinION, produced in part using technology licensed from UC Santa Cruz, to a select group of researchers at a cost of $1000, at least 50 times less costly than many common sequencers.

The name of the device, pronounced min-ion, combines mini and ion, though it reminds many of the cartoon Minions, yellow pill-shaped henchmen who comically struggle to serve an evil villain. The protein components inside the MinION are different than those developed at UC Santa Cruz, but the sequencing concept is the same: one protein, a helicase, controls the movement of DNA through a protein pore embedded in a membrane.

Rather than tailor the device for particular applications before its release, Oxford Nanopore borrowed a strategy from the tech industry. They enlisted a few hundred researchers, eager to use a MinION, to play with early versions of the device. The researchers tweeted pictures of their MinION experiments and shared troubleshooting tips with their colleagues in the company's online forums. Three years later, the MinION research community still gathers at twice-yearly conferences, hosted by the company in London and New York.

"There's lots of playfulness in the research community," said Christiaan Henkel, a biologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who was among the first researchers to use the MinION. "We all enjoy ourselves while doing important work," he said.

Henkel studies the genomes of unusual animals, like the European eel. There is less funding available to gather genome sequences from these animals, compared to common laboratory animals such as mice and zebrafish, he said. So, the MinION's affordability enables him to access the technology for his research, which can help eel biology, breeding, and conservation efforts. Eels are critically endangered, yet farming eels depends on catching young eels in the wild. Deciphering the eel's genome has improved scientists' understanding about its health, physical development, and population structure, information that can help biologists and ecologists coordinate fishing to maintain healthy wild eel populations.

Nanopore sequencing could also help tulip farmers in the Netherlands who lose up to 10 percent of their crop to fungi every year, said Henkel. The flower's lengthy life cycle means that new varieties can take 25 years to develop. Decoding the tulip's genome could provide information about which genes help resist disease, so that breeders can develop hardier varieties faster.

Identifying infectious microbes

Genome sequences provide important health information for humans, too. In August 2016, an astronaut aboard the International Space Station used a MinION to sequence samples of mouse, virus, and bacterial DNA in microgravity. Identifying microbes by their genetic sequences could help astronauts detect health threats. Back on Earth, researchers are testing the MinION for applications in medical diagnostics and infectious disease monitoring.

For serious infections like sepsis, severe pneumonia, and complicated urinary tract infections, rapid treatment with an effective antibiotic is key. MinION sequencing could identify infection-causing bacteria faster than, yet as effectively as, current culturing methods, said Justin O'Grady, a medical microbiologist at the University of East Anglia, UK. The genome also contains information about antibiotic resistance, providing doctors with clues about which drugs would not effectively treat an infection.

O'Grady and his colleagues have already used a MinION to identify bacteria, along with antibiotic resistance profiles, within four hours of receiving a urine sample in the lab. Since patients typically receive antibiotics every eight hours, rapid identification using genetic sequencing could help doctors prescribe a more effective drug before a patient receives a second dose of antibiotics, he said. "We can develop a diagnostic pipeline [that's rapid enough] to make a difference in the clinic," he said.

In February, the World Health Organization announced that the most common bacteria to cause urinary tract infections are becoming resistant to some antibiotics. Though genome sequencing for clinical microbiology is still in the research phases, O'Grady hopes it could eventually help patients receive appropriate drugs quickly, and ensure that doctors reserve the antibiotics effective against multi-drug resistant pathogens for when they are absolutely needed.

Other microbes, such as viruses and some parasites, can cause infections that spread quickly, sickening hundreds to thousands of people. For Jane Carlton, a biologist at New York University, the genome of the parasite that causes malaria is a basic tool to understanding its biology, ability to cause disease, and sensitivity to drugs. She, too, was part of the first group of researchers to use the MinION, and she thought the device's portability could change how she does research in rural India. Genomic information can be limited when infectious disease outbreaks happen in countries without access to the latest DNA sequencing technology. Developing the capacity for local scientists to sequence the genomes of infectious diseases such as malaria means that precious samples do not need to be sent to foreign labs, which can be expensive, logistically difficult, and take time.

Last year, Carlton and her colleagues brought MinIONs to India to sequence the genome of the malaria parasite from clinical samples. When their field station experienced frequent electrical shortages, the researchers took the MinION devices back to their hotel and continued sequencing overnight. A portable sequencer like the MinION means a lab can go to where it's needed, enabling local researchers to study the diseases that most affect their people, rather than relying on visits by foreign researchers, Carlton said.

Genomic information from clinical samples can help scientists document the spread of outbreak after it's occurred. But Nick Loman, a genomicist at the University of Birmingham, UK, thinks genomic information could also be used to stop an outbreak, provided researchers can quickly sequence clinical samples. Mutations in the genome of a virus or parasite help researchers track the microbe as it spreads to different communities, counties, or countries.

In December 2013, the largest Ebola outbreak in history began in West Africa, resulting in more than 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths. The first viral genome sequences collected from infected patients in Guinea publicly appeared in April 2014. In July, Ebola genomes sequenced from 99 patients in Sierra Leone confirmed that the outbreak had spread to another country. The next new sequences weren't available until mid-November, timing that left a genomic data gap during two months of rapid growth in the number of Ebola cases.

By March 2015, Loman, and his student Joshua Quick, had been working with the MinION for about a year as some of the early adopters. They realized bringing the sequencers to field research stations in West Africa could speed access to viral genomes, so they teamed up with European researchers operating a mobile laboratory in Guinea. In April, Quick carried suitcases of equipment for a portable MinION-based genomics lab to Guinea where he sequenced samples at the field station for two weeks and then trained other researchers to continue the process. The team sequenced Ebola from 142 patient samples collected from March to October 2015, generating results within 24 hours of collecting samples. Two local researchers continued the MinION sequencing at least through February 2016.

Back to the beginning

As the MinION provides current genetic information at remote sites around the world, Akeson and Deamer are using nanopore sequencing to dive further into the past.

Akeson and his students, along with others in the MinION research community, are sequencing RNA, the chemical cousin of DNA. One type of RNA, found in ribosomes, accumulates mutations so slowly that tracking sequence changes between different organisms can reveal millions of years of evolution.

Deamer, meanwhile, is returning to questions about the origins of life that first inspired his idea for nanopore sequencing: He's using the MinION to decode DNA produced by primitive cells, hoping to show they are producing molecules that resemble genetic information.

The evolution of nanopore sequencing started with an idea sparked on a road trip, grew out of early experiments inspired by attending talks at conferences, and developed into a technology now used around the world. For Deamer, the story of nanopore sequencing reveals the serendipitous path of science: "You have to have your brain wide open to all these patterns. There are a whole bunch of balls out there, and if you pick the right bunch, you can juggle them and do some tricks."

Additional reporting contributed by Laurel Hamers, SciCom '16