Forcing evolution's hand

When humans build, nature remodels

When early settlers landed on America's eastern shores in the 1600s, most new communities did two things: they built a church and a dam. The consequences of those dams persist today.

While blocking the flow of rivers and streams made it possible for pioneers to power up their mills, the dams also shut off the natural journey of the anadromous alewife—a river herring that spends most of its life in the ocean but must return to rivers to spawn. In response to this new lifestyle, the alewife consigned to inland waters underwent dramatic physical changes.

As the fish developed new traits to survive in their altered surroundings they, in turn, transformed their ecosystem, a phenomenon that lures Eric Palkovacs, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. He investigates the ways that human impacts on the natural world affect the rate at which a species evolves, a process known as eco-evolutionary dynamics.

Palkovacs' research shows that when anthropogenic activities force organisms to modify their physical traits to survive, those small evolutionary steps can also alter the environment—creating unintended consequences for people, too.

Isolating alewife

In the case of the alewife, several hundred years of segregating lake-locked alewife from their ocean-migrating brethren led to smaller body sizes, smaller mouth gape, and different spacing of their gill rakers—all traits designed to capture smaller food. Why? Because to survive, they had to evolve to forage on the tinier stuff; their lake-bound behavior had disrupted the ecosystem in which their anadromous ancestors had evolved.

Normally, when alewife migrate to lakes or rivers to spawn, they feed on the larger animal plankton. Eventually, the fish swim for open seas and the large zooplankton populations bounce back. But alewife trapped behind dams couldn't leave, so the larger plankton populations never rebounded. That change in feeding behavior had a cascading effect: not only did the fish need to find smaller plankton, but with few large animal plankton remaining, the microscopic algae bloomed out of control.

Alewife disrupted the ecology of lakes elsewhere, too. While growing up, Palkovacs witnessed massive die-offs of alewife in the '80s; fish littered the shores of Lake Michigan after they invaded the upper Great Lakes. There, zooplankton populations —decimated by the surge of alewife—weren't large enough to keep the smaller plant plankton in check, a situation that likely exacerbated the algal blooms already overwhelming the Great Lakes. Alewife also reduced native whitefish populations that competed for the same food.

Evolving questions

Now, years later, Palkovacs investigates how those fish made it from the ocean to the Great Lakes by tapping into the genetics expertise and cutting-edge equipment at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Southwest Fisheries Science Center based in Santa Cruz —UC Santa Cruz's next-door neighbor. Not only does he collaborate with NOAA scientists, which helped to expand the diversity of his genetics work, but Palkovacs is also the director of the NOAA Cooperative Institute that supports NOAA and UC Santa Cruz partnerships.

With all these resources, Palkovacs also studies mosquitofish, trout, stickleback, salmon, and green sturgeon. Each of these species has been altered by human activities: from blocked waterways to warming water temperatures. In every field setting he poses the same eco-evolutionary questions: How are humans forcing these organisms to change, and how do those changes affect their survival?

While evolution likely conjures a timescale of thousands of years, it can also happen fast, "on the order of years and decades," said Palkovacs. These trait changes, or rapid evolution, can occur from a behavioral change in response to an altered ecosystem, or from hunting and fishing. When people place selective pressure on animal populations, like killing bigger fish or larger-horned sheep, within a few generations the animals can evolve new traits. They may start to mature at a younger age, shrink in size, or shift their migration behavior. "This happens whenever we kill stuff," said Palkovacs. "We often select against the traits that we actually value."

Damming evidence

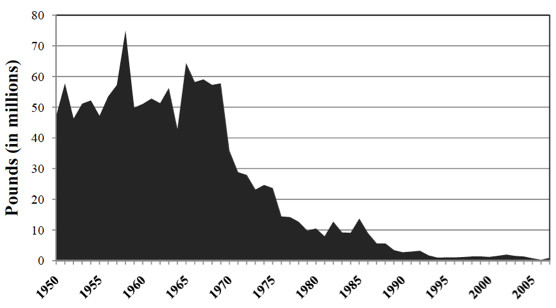

The anadromous populations of alewife have steadily declined since the 1970s. A variety of culprits were put on the table: dams, pollution, freshwater harvests, predators, and now people are suggesting effects from climate change, explained Palkovacs. "And then there's marine bycatch," he added.

Palkovacs' background in population genetics drove him to search for reasons why alewife numbers continued to dramatically drop along stretches of the Eastern Seaboard, despite years of improving pathways for fish, protecting water quality, and setting limits on freshwater harvests. He surmised the only thing left relatively unchecked was their vulnerability as bycatch; trawl nets targeting oceanic Atlantic herring accidentally scoop up blueback herring and alewife swimming among them.

To test his hypothesis, Palkovacs and his partners at NOAA turned to a database they built with nearly 8,000 specimens of alewife and blueback herring collected in rivers from Florida to Canada. Using non-lethal snips of fish fins, they catalogued the river herring's genetic fingerprints and linked each fish to a region of rivers. The scientists could then match the genetic fingerprint of each bycatch-caught alewife and blueback herring to their spawning rivers.

The results of this work showed that the threatened East Coast alewife populations are from rivers in southern New England and the Mid-Atlantic—areas that Palkovacs said "really do overlap strongly with areas where they find the greatest magnitude of bycatch."

This DNA detective work also revealed to Palkovacs the extent to which these foot-long fish travel up and down the coast, and their susceptibility to ending up as bycatch. "We can't say with 100 percent certainty that it [bycatch] caused past declines, but I can say it's contributing to their lack of recovery," he said.

Palkovacs' alewife bycatch research garnered attention at the last Mid-Atlantic fishery management council meeting when members voted on whether to federally protect the river herring. Although he presented strong evidence for alewife decline along a large swath of the coast, the council focused on less- certain evidence of alewife populations improving in Maine, he noted. In the end, the council opted not to grant federal status to river herring under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, which requires a thorough population assessment that reveals how much river herring can be sustainably fished.

That designation would have provided legal teeth to prevent overfishing, explained Palkovacs, which alewife don't currently have because they aren't directly harvested. "They are in fisheries management limbo," he said.

Alewife return to their original spawning streams less frequently than Pacific salmon. Migrating between several rivers means alewife aren't as genetically differentiated as salmon, explained John Carlos Garza, an ocean sciences adjunct professor at UC Santa Cruz and NOAA geneticist who works closely with Palkovacs on river herring. Without data showing distinct alewife populations (stocks) for each river, the fish don't fit into neat biological categories that fisheries managers need. This makes managing alewife complex if they fare better in some rivers and not others.

"When you see populations declining over your own career, it's disconcerting," said Palkovacs, who once saw tens of thousands of these fish during his doctoral studies in 2005, but now sees only hundreds.

Fishy encounters

Now, many of those dams from the 1600s have been dismantled, giving fish the upstream access they once had. Connecticut's Rogers Lake, for instance, has a new fish ladder, and Palkovacs and his team have a unique opportunity to monitor a natural evolutionary experiment from the outset: What happens when ocean-migrating fish finally reconnect with their lake-bound family nearly 350 years later?

By taking fin clips as the fish enter the lake and from those already in residence, scientists can determine if the two groups interbreed or whether one group dominates. They can also follow how the lakes respond ecologically; for instance, ocean-migrating fish bring marine nutrients to a lake system. "Is the process of reconnecting these populations going to provide overall benefit, or might it be the opposite?" said Garza.

While many people may overlook alewife, they are a keystone species for lakes, said Andrew Hendry, professor of evolutionary biology at McGill University in Montreal and a noted author on eco-evolutionary dynamics. He believes alewife demonstrate the importance and consequences of evolutionary dynamics. In addition to being a contemporary and reproducible study, Palkovacs' alewife research occurs in a natural setting, said Hendry, which is an advantage over studies in controlled lab settings that can't always show the magnitude of evolutionary change.

Altered lives

On the West Coast, steelhead trout have an ecological story similar to that of alewife. They, too, battle for clean water, spawning habitat, and unobstructed river access. Though steelhead trout migrate between the ocean and rivers, they can also become a permanent freshwater resident in the form of a rainbow trout—the same species, Oncorhynchus mykiss, with a different lifestyle.

Scientists recently discovered that genetics and body size trigger whether a rainbow trout becomes a lake resident or decides to migrate as a steelhead. "We've found that when steelhead are isolated above barriers we can see on a molecular level that they undergo selection against migratory behavior," said Garza.

By constructing dams across a river, "humans can tip the balance in what they prefer," said Palkovacs.

Additionally, the human propensity to harvest the biggest fish has, over time, led to a smaller body size and younger spawning age in wild salmon— the steelhead's cousin. Selecting bigger fish is commonplace in fisheries. "But that can reduce the productivity of a fishery, decrease its resilience to environmental change, and have negative impacts for people that rely on those fisheries," said evolutionary biologist Hendry.

The effects of culling bigger predators reverberate down the food chain. For instance, there are fewer eggs to develop into more salmon, less fish to control their prey, and less marine nutrients to enter a river system. To learn how consistent that decline is across Alaska's rivers and salmon species, Palkovacs is leading a group of scientists to comb through 50 years of historical data to tease out how harvesting, food availability, and warming ocean temperatures may work collectively to cause Alaskan salmon to shrink.

Good documentation has been lacking, said Palkovacs, to show that fish are changing size, that those changes are evolutionary, and that humans feel the impacts. So, by wading deeper into this Alaskan salmon issue, Palkovacs wants to know: How do these human-induced changes circle back to humans?

For example, subsistence Native Alaskans feel the economic and cultural impacts. "Now it takes two or three modern fish to make up the biomass of a historically sized Chinook in the Yukon River," said Palkovacs. It requires more effort to catch enough fish to fill their freezer for the winter.

While it's easy to understand how mass extinctions can drastically alter ecosystems and species, human activity can also trigger ecological shifts that force species to adapt in small, but continuous, increments. Palkovacs' research shows how our actions can also come back to damn us.