A lab in the hand

High-tech creates low-cost medical tests

In the late summer of 2014, new Ebola virus cases in West Africa jumped from around 150 to more than 500 per week. With no vaccine and no cure, quarantining infected individuals was the only hope to halt the epidemic.

Suspected Ebola patients—those with high fevers and potential viral exposure—could wait up to a week in cramped, makeshift “holding centers” while their blood samples were tested at the few diagnostic labs. A Doctors Without Borders study conducted at the height of the epidemic found that more than a third of the patients initially diagnosed with the virus returned a negative blood test. These patients may have come to the clinic with malaria or Lassa fever but left having been exposed to Ebola virus, which spreads readily through saliva, blood, and other bodily fluids.

There’s no way to estimate how many patients might have been infected in the holding centers, the study concluded. But the situation demonstrated the critical need for point-of-care diagnostic tests that were accurate, fast, affordable, easy to administer and read, and didn’t need an external power source.

While other researchers have focused on miniaturizing current laboratory techniques to create “lab-on-a-chip” devices that rely on chemical reactions to detect the virus, two researchers at UC Santa Cruz took a different approach—exploiting the behavior of light on the micro- and nanoscales to reveal Ebola molecules directly. Initial results indicate these lab-on-a-chip prototypes could be as sensitive as the current gold standard tests, at a fraction of the cost.

Finding Ebola’s code

The gold standard Ebola test uses a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (or RT-PCR) to amplify the viral genetic material and tag it with fluorescent molecules. Hit these tags with a specific color of light and they re-emit it as a different color. For example, violet light converts to green, and the green light’s intensity is measured by a sensor.

This process takes more than two hours and requires specialized lab equipment, exotic chemicals, and trained technicians. Even a few contaminating Ebola molecules from another patient’s sample can return a false positive result. All these factors add up to around $100 per test, about a third of the average yearly salary in West Africa.

For emergency use during the most recent epidemic, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a far simpler commercially available device called the ReEBOV Antigen Rapid Test, made by Corgenix Medical Corporation. Reminiscent of a color-change pregnancy test, it uses an antibody-laden strip which changes color when it binds Ebola proteins in the blood. The test takes about 15 minutes and costs around $10.

While the ReEBOV is slightly less accurate when compared in a lab to RT-PCR, in field tests the device matched the RT-PCR results 100 percent of the time. Robert Garry, a virologist at Tulane University in Louisiana, who helped design and test ReEBOV, noted that sensitivity mattered less because “people with such low levels of the virus aren’t showing up at the clinics.”

However, Ebola’s aggressive nature makes early viral detection a priority.

“One would like to test, isolate, and treat lots of people before they show symptoms and are already approaching death,” said UC Santa Cruz electrical engineer Holger Schmidt. In an article published in Nature Scientific Reports, his lab demonstrated a lab-on-chip that could sift through extracts of human cells infected with Ebola and detect as few as two infectious particles in ten milliliters—about two teaspoons—of sample.

Rather than trying to amplify DNA on a microscale, Schmidt built a device that simply counts virus RNA genomes. “Let’s say we run one milliliter [of sample] through our chip,” he said, “however many blips we get, that’s the viral load.”

Schmidt’s background is in physics, studying the quantum effects of light in semiconductor devices. When he joined the faculty at the Baskin School of Engineering, he developed an approach to coax light through gas vapors on a chip, and then applied them to liquids, specifically liquids containing biological molecules.

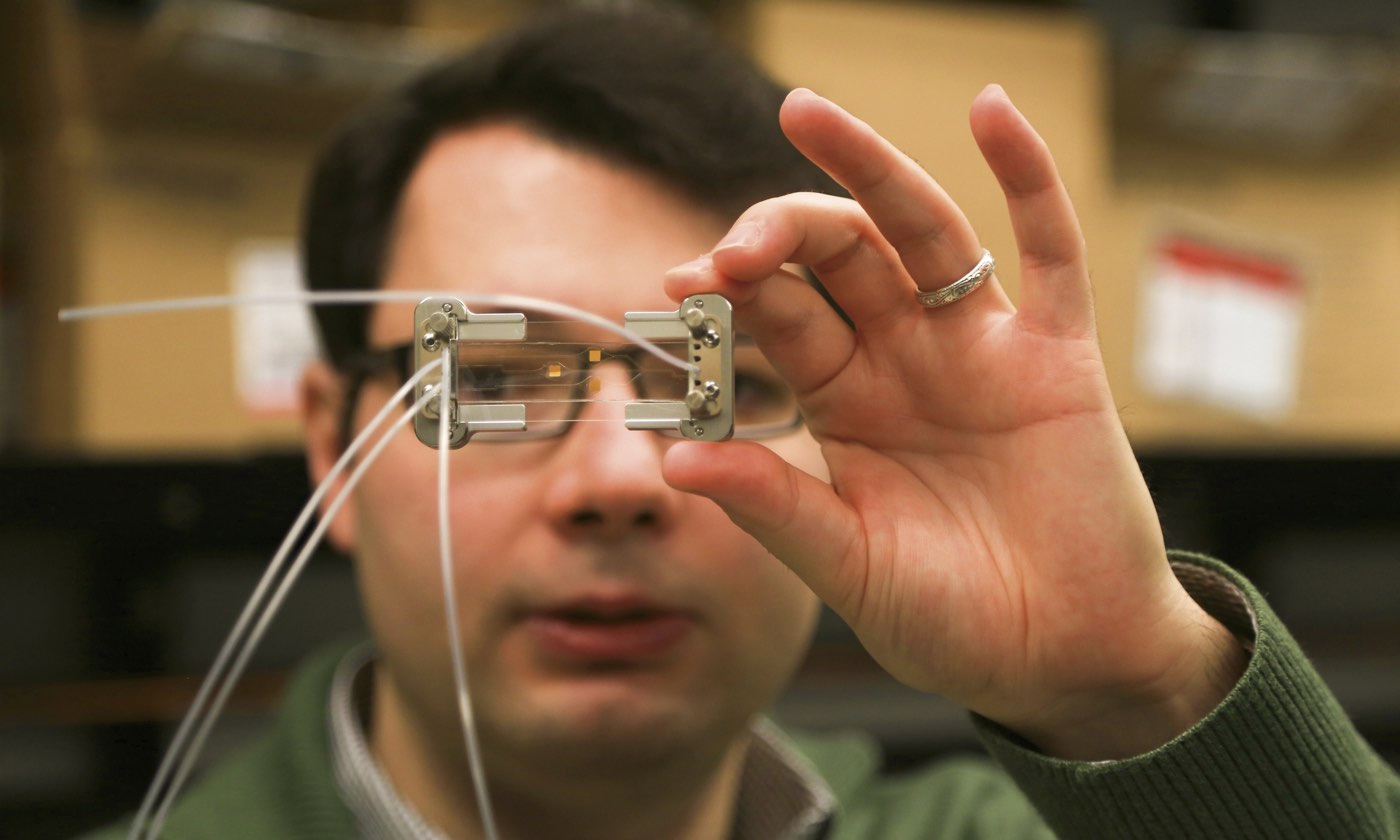

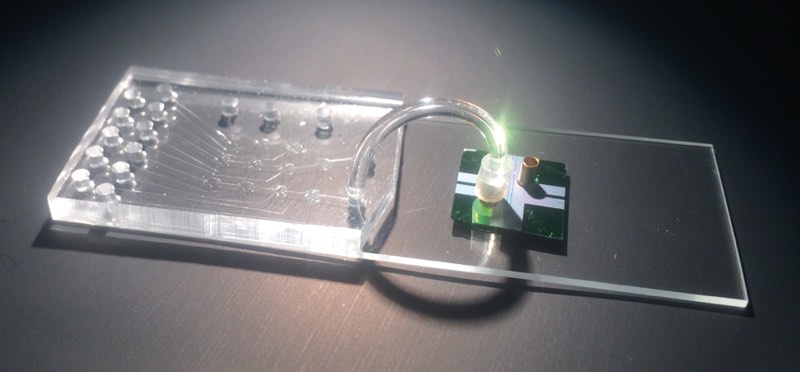

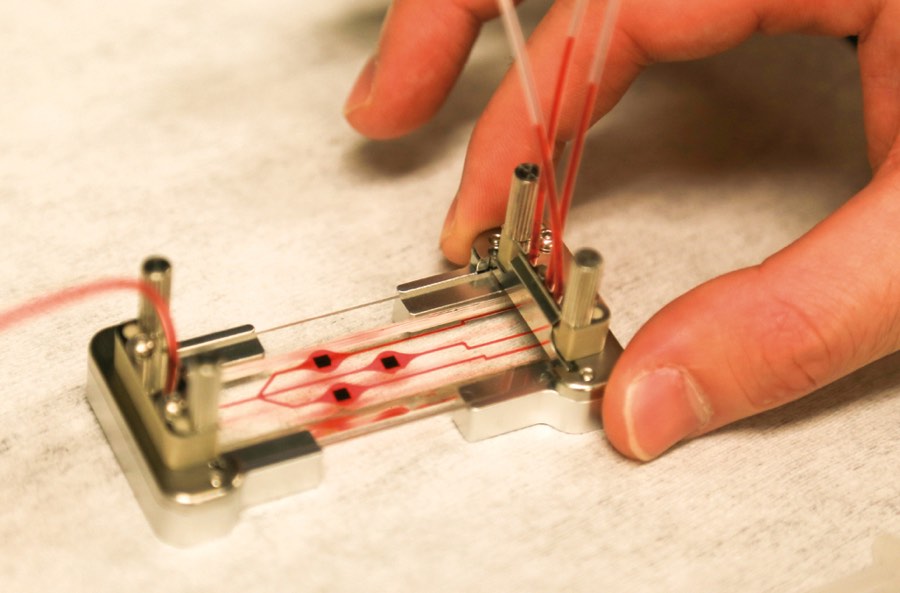

The idea to analyze single biomolecules on a chip came from conversations with David Deamer, a UC Santa Cruz biomolecular engineer who developed techniques to glide strings of DNA through sub-microscopic holes, called nanopores, to study the DNA’s molecular bonds. With collaborators that include a chip-manufacturing group, Schmidt’s group produced a two-chip hybrid device. The clear silicon-based microfluidics chip isolates individual molecules from the sample and chemically preps them for detection on the second optofluidics chip. The two are joined by flexible tubing and the whole system is about the size of a microscope slide.

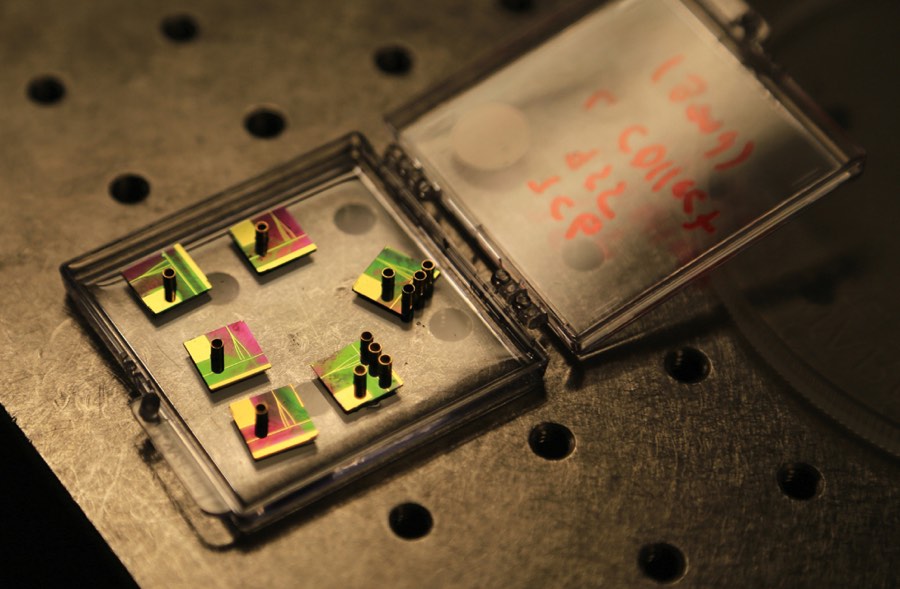

The thumbnail-sized optofluidics chip resembles a piece of modern jewelry, with tiny copper cylinders rising above iridescent patches that shimmer pink to green in changing light. The cylinders hold the solution containing Ebola RNA with fluorescent tags, and then release the molecules, one by one, into liquid-filled channels that look like golden hairs etched into the chip. Other golden lines are the solid channels that carry light. Where the channels intersect, the light flows through the liquid and any passing molecule. As in RT-PCR, light is absorbed and released as a different color. But because the tagged RNA passes through single file, the optofluidic’s sensor can count each flash, or, as Schmidt likes to call it, “blip.”

Schmidt’s device is generic. Proteins, viruses, and even small bacteria can be tagged and counted. “We use exactly the same chips. One day we test Ebola, the other day cancer markers,” said Schmidt. This non-specificity will help keep costs down to one or two dollars per device.

While Schmidt’s device is disposable, it needs an external case to supply electric power and light. The device doesn’t quite snap in; the fiber optic cables’ alignment needs to be manually adjusted by microscrews—a process Schmidt said will be automated in the final prototype. His lab is also optimizing the microfluidic system to be faster and capable of running larger volumes of starting sample.

By the end of the year, they plan to deliver a portable external case to be installed, permanently, at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute’s biosafety level-4 lab in San Antonio. There, technicians trained in virology, not optics, will test the devices on live viruses.

“They’ve come up with a very good solution that is state-of-the-art,” said Ajeet Kaushik, a bioengineer at Florida International University, in Miami. An immunologist by training, he’s reviewed various point-of-care Ebola diagnostic technologies, including an Ebola protein detection device under development by Ahmet Yanik, UC Santa Cruz electrical engineer.

Naked eye detection

Unlike viral diagnostic tests that rely on chemical reactions to make the proteins visible, Yanik’s idea is to simply use light “in a label-free manner, no enzymatics, no fluorescence, to see proteins directly.”

The device he designed works because of a curious optical phenomenon called the extraordinary light-transmission effect.Shining light through an arrangement of holes that are narrower than the light’s own wavelength produces much more light than beaming it through one big hole.

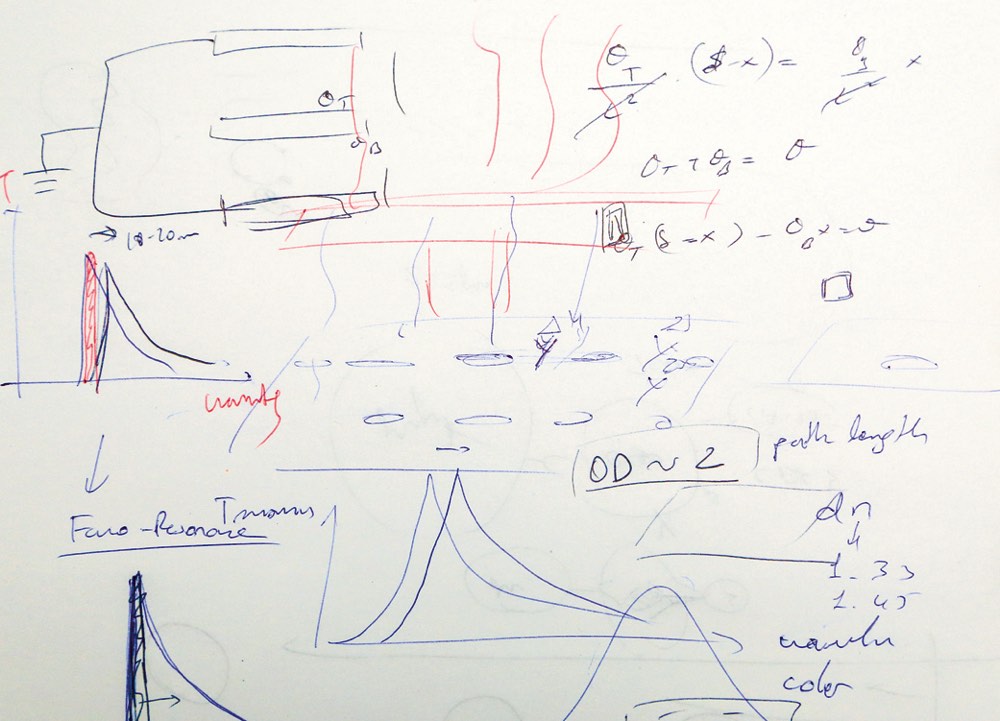

As he talked, Yanik scribbled down graphs, diagrams, and formulas on printer paper. He hastily filled in the page with four to six images before flipping it over to explain the next concept.

“The nanoholes are so small,” said Yanik, “light shouldn’t be able to pass through them.” But it does, through its interaction with the nanohole surfaces. By coating the nanoholes with different antibodies, Yanik can use the device to bind any protein—cancer markers, drugs, or even a whole virus. When he captured killed Ebola biomarkers on the nanoholes, the transmitted wavelength (or color), shifted about 15–20 nanometers. That’s too subtle for our eyes to see, but easy to measure electronically.

As a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard, Yanik developed a device that worked great in a state-of-the-art hospital lab. He jokingly called it the “chip-on-a-lab” system. To take the chip out of the lab, he figured out how to constrict the wavelength range that could pass through the nanoholes.

On paper, Yanik drew two sharp peaks with almost no overlap to show the light transmitted with, and without, the attached virus. Place a filter over the device to cut out the longer wavelengths and the material with the nanoholes turns from translucent to opaque. When the virus binds, said Yanik, “you have complete darkness.”

He flipped another page. Light detection is not the only hurdle, said Yanik. Blood is thick with proteins that can bind randomly in the nanoholes, shifting the light and causing a false positive reading. Equally critical is making sure the test works quickly—it isn’t practical to wait six hours to decide if someone should be quarantined.

Since starting his UC Santa Cruz lab in February 2014, Yanik and his graduate students have tackled these problems. Now they hope to have a device in production within a year or two. Over time, the pitch for his device has changed. It used to be all about responding to biological threats from terrorists. Now his presentations include a slide listing the leading causes of death in the developing world; almost all are infectious diseases.

“In this lab,” said Yanik, “I can detect anything. But can I do that in the far corners of the world? It seems that is where you can make a huge impact.”